Nicola Griffith’s foray into historical fiction, Hild, has been hugely successful. The book won a Lammy and was a finalist for a bunch of other major awards, including the Nebula, Otherwise and Campbell. (Yes, that Campbell which is an award for science fiction novels). Given that the book only covered the early years of the life of Hild of Whitby, a sequel was pretty much inevitable. Of course, with the amount of research that Griffith puts into these books, it wasn’t going to come quickly. However, Menewood is officially due on October 3rd. Griffith kindly sent me an ARC to look at.

Nicola Griffith’s foray into historical fiction, Hild, has been hugely successful. The book won a Lammy and was a finalist for a bunch of other major awards, including the Nebula, Otherwise and Campbell. (Yes, that Campbell which is an award for science fiction novels). Given that the book only covered the early years of the life of Hild of Whitby, a sequel was pretty much inevitable. Of course, with the amount of research that Griffith puts into these books, it wasn’t going to come quickly. However, Menewood is officially due on October 3rd. Griffith kindly sent me an ARC to look at.

This is history, so some things about Hild’s life are way beyond the statue of limitations for spoilers. When we left her, she was riding high as a valued advisor to her uncle, King Edwin of Northumbria. Also she had just got married to her childhood friend, Cian, and the two of them had their own estates to run in Elmet (the area around modern day Leeds). However, anyone with access to Wikipedia will know that Edwin’s reign was cut short thanks to an attack by King Penda of Mercia, backed up by the vicious Cadwallon of Gwynedd. Hild must have survived, and Menewood sets out to tell the story of those turbulent years.

Just like Hild, Menewood is real. These days it is a suburb of Leeds, just to the east of Headingly, where Griffith grew up. (The modern name is spelled Meanwood, which is far less glamorous.) One of the things that shines through in the book is the sense of place. You get the impression that Griffith has walked the many locations featured in the novel, or at least surveyed them on Google Earth, and taken as keen an interest in their geography as her hero does.

The thing you have to do when your country is laid waste by foreign invaders is rebuild, pretty much from scratch. In early mediaeval England that means skills in farming and a whole bunch of associated crafts such as housebuilding, metalworking and brewing. Hild can’t do all of these things (she’s not a Heinlein hero), but Griffith gives her good people management skills. Building a village is much like building a company. You want the right people in the right jobs. In order to write this, Griffith has had to find out how all these things were done in Hild’s time. That’s a whole lot of research, which I’m sure will delight her readers. Nevertheless, the book never feels infodumpy.

Having rebuilt, the next step is to secure peace, by making sure that the enemy will never be able to invade you again. Penda, it seems, is not much of a problem. His strategy seems to be one of patience and caution. He keeps Mercia safe, not by conquering neighboring kingdoms, which might cause him to overstretch, but by attacking and destabilizing them, then moving on. Having done for Edwin, he’s turning his sights on the Angles, amongst whom Hild’s sister, Hereswith, is likely to become queen. That, I suspect, will be the focus of the next book in the series. (Edwin was an ally of Rædwald, the most likely occupant of the grave at Sutton Hoo.)

Cadwallon is another matter. He’s not interested in being a king. He’d much prefer to be a terrifying warlord who takes his men where he wants, kills who he wants, and takes their gold. Bede tells us that he was an awful person, and someone who Bede says is bad, even for the British, must be very bad indeed.

I used the word, ‘British’, there because many of the inhabitants of the ex-Roman province of Britannia still regard themselves as citizens of the country they called Prydain before the Romans arrived. They speak a language that is recognizably a precursor of modern Welsh, Cornish and Breton. Hild’s people call them Wealh (Welsh) – foreigners. The newcomers are from many parts of the Germanic world and do not yet call themselves Saxons, but the British call them Saes (Saesneg, Sassenach), which also means foreigners.

Hild is at pains to make her people tolerant of ethnic differences. She tells them that they are Elmetsæte first, regardless of what god they worship or language they speak. This sems entirely fitting, both for her later career as a diplomat, and for the fact that the author is a Yorkshire lass with the fine Welsh name of Gruffydd.

Having laid waste to modern Yorkshire, Cadwallon heads north to the Roman wall and beyond, murdering and plundering as he goes. Bede tells us that he met a sticky end in the north at the hands of one Oswald, a cousin of Hild whose family fell foul of Edwin and ended up hiding out in the Irish kingdom of Dál Riada in the West of Scotland. How this came to pass is a mystery, and one that Griffith sets out to explain.

A word of advice. If you are into wargaming, do not take on Griffith. She has an excellent eye for strategy and tactics, and will beat you hollow.

The final element of the book is Hild’s personal journey. She is not yet at the point of embracing Christianity and becoming a saint, and that part of her life may make a fascinating fourth volume. Currently she’s still happy to embrace any faith, be it worship of Woden, or any of the varieties of Christian worship vying for dominance, as long as it works for her. But she still has a lot to learn. To rebuild her community she needs to become a woman of the people, which is hard for someone raised as royalty. I’m pleased to see that she ends up treating her former body slave, Gwaldus, much better than she did in the first book.

By the way, Gwladus is a British woman from Somerset, so I have a soft spot for her. Griffith gives her own pronunciation guide in the book, but I’m here to tell you that Gladys is not a bad modern Welsh version of the name.

I should note that the book takes an entirely realistic attitude to early mediaeval sexuality. Many characters are enthusiastically bisexual, and no one fetishizes virginity. The small number of fanatical Christians probably disapprove, but no one pays them any mind. That will change, and I look forward to seeing how Hild reacts to it.

Hild also knows that she can’t be king. In a warrior society like hers, strong men always end up in charge, and a woman on the throne simply marks your kingdom out as a target for neighbouring kings. Besides, being king is an awful job. You have to keep killing people in order to stay on the throne, and Hild doesn’t want to do that. There are a number of characters who use more traditionally feminine paths to power, most notably Langwredd, the British princess whose lands lie north of the wall. Griffith, being who she is, has Hild do things very differently, and it is fascinating to observe.

Talking of powerful women those of you who follow the resurrected Time Team may know that they recently excavated an early mediaeval graveyard in East Anglia, and in particular the grave of a high status Christian woman. They don’t know who she is, or why she was buried there, but the dates would work for it being Hereswith. Some of the grave goods are from Frankia (the land of the Franks in modern-day France). Bede says that she entered a monastery there to live out her days, but the Abbey he says she went to wasn’t founded until after her death, and anyway he doesn’t explicitly say she died there. She may have come home when her son, Ealdwulf, became king of the Angles. I should note that the woman in the grave is very short and petite, which is very unlike the tall, imposing Hild, but Hild’s stature is a Griffith invention.

The book is long – over 700 pages in PDF – but very much worth your time, especially if you have any interest in early mediaeval Britain. I expect it to be hugely popular with historical fiction readers, and with a bunch of my historian friends. I note that Dr. Griffith was a guest speaker at the prestigious International Mediaeval Congress this year (which just happened to be in Leeds this year).

Menewood is not fantasy. It does include a brief appearance from someone who might have inspired a famous legend, but that’s hardly a key part of the story. It is much more important to note that Hild’s people, and her enemies, are all convinced that she can do magic because she is very smart and notices things that most people would miss. Griffith doesn’t write the book as magic realism, but she could easily have done so. Don’t let the lack of magic put you off reading it. It is a far better evocation of that period of British history than most fantasy novels I’ve read.

Of course you don’t need me to tell you this. In a few months time the mainstream media will be full of praise for Menewood. I’ll just pick up a hardcover to put next to my copy of Hild and wait patiently for book 3.

Title:

Title: Menewood

By: Nicola GriffithPublisher: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Purchase links:Amazon UKAmazon USBookshop.org UKSee

here for information about buying books though

Salon Futura

This is the July 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the July 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Menewood

Menewood Dragonfall

Dragonfall Good Omens – Season 2

Good Omens – Season 2 Nimona

Nimona Promises Stronger Than Darkness

Promises Stronger Than Darkness Pemmi-Con

Pemmi-Con The Pemmi-Con Masquerade

The Pemmi-Con Masquerade Black Adam

Black Adam The Western Kingdom

The Western Kingdom Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves Editorial – July 2023

Editorial – July 2023 This issue sees the second in my series of covers donated by Iain J Clark from the collection of images he has created for the Glasgow in 2024 Worldcon. This one is called “Sailing over Glasgow” and presumably celebrates the shipbuilding industry of the Clyde.

This issue sees the second in my series of covers donated by Iain J Clark from the collection of images he has created for the Glasgow in 2024 Worldcon. This one is called “Sailing over Glasgow” and presumably celebrates the shipbuilding industry of the Clyde.

Nicola Griffith’s foray into historical fiction, Hild, has been hugely successful. The book won a Lammy and was a finalist for a bunch of other major awards, including the Nebula, Otherwise and Campbell. (Yes, that Campbell which is an award for science fiction novels). Given that the book only covered the early years of the life of Hild of Whitby, a sequel was pretty much inevitable. Of course, with the amount of research that Griffith puts into these books, it wasn’t going to come quickly. However, Menewood is officially due on October 3rd. Griffith kindly sent me an ARC to look at.

Nicola Griffith’s foray into historical fiction, Hild, has been hugely successful. The book won a Lammy and was a finalist for a bunch of other major awards, including the Nebula, Otherwise and Campbell. (Yes, that Campbell which is an award for science fiction novels). Given that the book only covered the early years of the life of Hild of Whitby, a sequel was pretty much inevitable. Of course, with the amount of research that Griffith puts into these books, it wasn’t going to come quickly. However, Menewood is officially due on October 3rd. Griffith kindly sent me an ARC to look at.

Following an author’s career can tell you quite a bit about them as a person. Some writers who have achieved success seem content to keep pumping out what works each time, for less and less effort. Others are determined to stretch themselves with each new book and get better at their craft. L R Lam is definitely in the latter category.

Following an author’s career can tell you quite a bit about them as a person. Some writers who have achieved success seem content to keep pumping out what works each time, for less and less effort. Others are determined to stretch themselves with each new book and get better at their craft. L R Lam is definitely in the latter category.

As you probably all know, Gaiman and Pratchett had plans for a follow-up to Good Omens, but their careers took off so fast that neither of them had the time to make it happen. When the TV series was a success, Gaiman used those plans as the basis for a second series. Exactly what was in those plans is unknown, and doubtless fans will argue endlessly over it, but the important question is whether the resulting series lived up to the standards set by the first. Well reader, I was delighted with it.

As you probably all know, Gaiman and Pratchett had plans for a follow-up to Good Omens, but their careers took off so fast that neither of them had the time to make it happen. When the TV series was a success, Gaiman used those plans as the basis for a second series. Exactly what was in those plans is unknown, and doubtless fans will argue endlessly over it, but the important question is whether the resulting series lived up to the standards set by the first. Well reader, I was delighted with it. When I said that I did not expect to see a better film than Across the Spider-Verse this year, I really was not expecting to see another brilliant animated film just a couple of weeks later.

When I said that I did not expect to see a better film than Across the Spider-Verse this year, I really was not expecting to see another brilliant animated film just a couple of weeks later. Let us recap. The Unstoppable series by Charlie Jane Anders is space opera, but it is not your father’s space opera. Iain Banks would never have called a starship, Undisputed Training Bra Disaster. Nor, after successfully blowing an enemy starship to atoms, would a group of Culture heroes engage in a lengthy debate as to whether their actions were morally justified, and who should be held responsible for this war crime. Queer YA space opera is, in some ways, a very different beast.

Let us recap. The Unstoppable series by Charlie Jane Anders is space opera, but it is not your father’s space opera. Iain Banks would never have called a starship, Undisputed Training Bra Disaster. Nor, after successfully blowing an enemy starship to atoms, would a group of Culture heroes engage in a lengthy debate as to whether their actions were morally justified, and who should be held responsible for this war crime. Queer YA space opera is, in some ways, a very different beast.

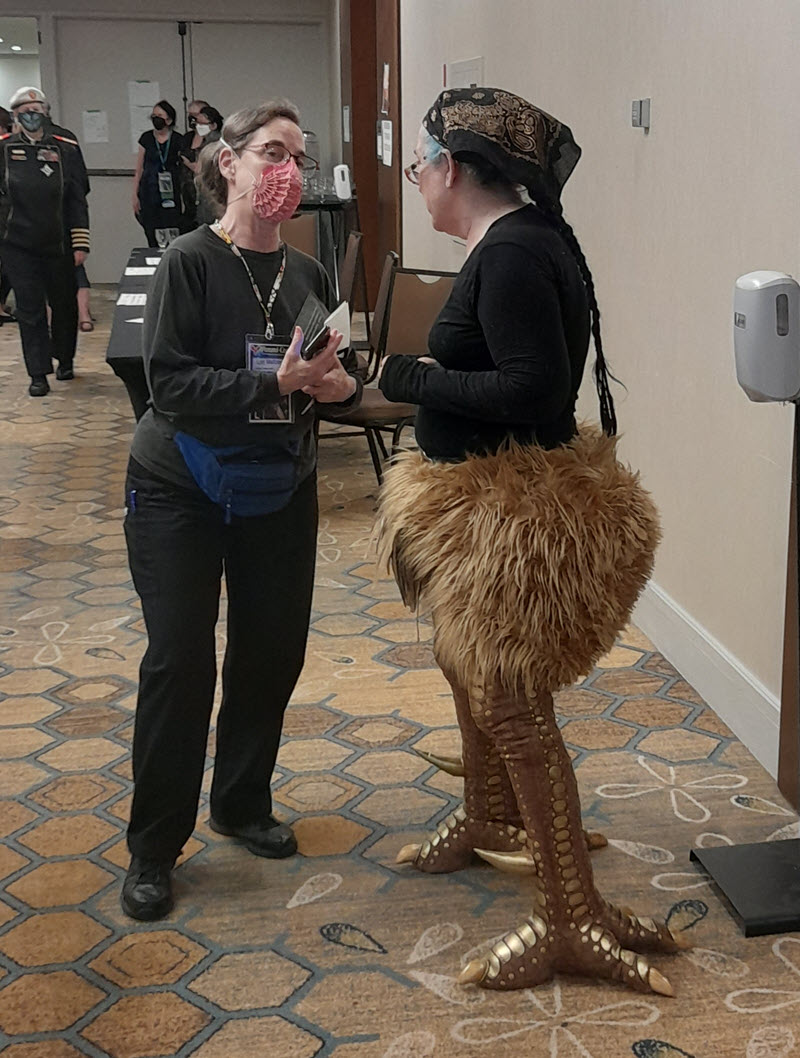

NASFics are strange beasts. It is sometimes said that running a NASFiC is rather like trying to run a Worldcon with half the money and half the attendees. I might also add half the volunteers to that. And, in the case of Pemmi-Con, “half” is probably a massive exaggeration on all counts.

NASFics are strange beasts. It is sometimes said that running a NASFiC is rather like trying to run a Worldcon with half the money and half the attendees. I might also add half the volunteers to that. And, in the case of Pemmi-Con, “half” is probably a massive exaggeration on all counts. Getting a quality masquerade from a convention with only just over 500 attendees is a challenging task, but somehow Sandy Manning managed it. There were a bunch of top quality costumers who came up from the USA and provided some master-level entries and judges, but it was particularly pleasing to have 4 young entrants, none of whom had ever been on stage before. Congratulations in particular to Turaga Vakama who used 3D printing to create what I assume was an anime costume.

Getting a quality masquerade from a convention with only just over 500 attendees is a challenging task, but somehow Sandy Manning managed it. There were a bunch of top quality costumers who came up from the USA and provided some master-level entries and judges, but it was particularly pleasing to have 4 young entrants, none of whom had ever been on stage before. Congratulations in particular to Turaga Vakama who used 3D printing to create what I assume was an anime costume.

This is another film that I watched on the plane on my way to Toronto. It being mostly superhero fight scenes, it doesn’t really warrant watching on a big screen, but it does have a lot more to the script than the Dungeons & Dragons film.

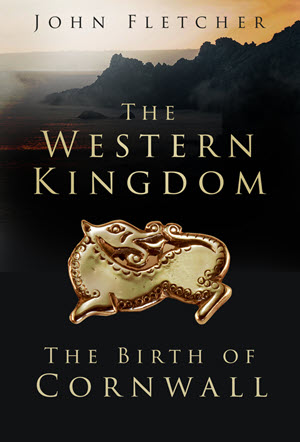

This is another film that I watched on the plane on my way to Toronto. It being mostly superhero fight scenes, it doesn’t really warrant watching on a big screen, but it does have a lot more to the script than the Dungeons & Dragons film. It might look like it from the cover, but this is not a fantasy novel. As the subtitle explains, The Western Kingdom is a history of the birth of the Kingdom of Cornwall, probably the oldest kingdom in the UK.

It might look like it from the cover, but this is not a fantasy novel. As the subtitle explains, The Western Kingdom is a history of the birth of the Kingdom of Cornwall, probably the oldest kingdom in the UK.

I watched this film on the flight from Zurich to Toronto. Airline entertainment systems are in no way a good choice for viewing movies (other than being free and you are trapped in your seat), but I don’t think that matters here because this movie has no pretensions.

I watched this film on the flight from Zurich to Toronto. Airline entertainment systems are in no way a good choice for viewing movies (other than being free and you are trapped in your seat), but I don’t think that matters here because this movie has no pretensions.

This is the June 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the June 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Furious Heaven

Furious Heaven Translation State

Translation State Salt on the Midnight Fire

Salt on the Midnight Fire Across the Spider-Verse

Across the Spider-Verse Witch King

Witch King The Unraveling

The Unraveling Hild

Hild Eurocon 2023

Eurocon 2023 Vikings at Uppsala

Vikings at Uppsala Heilung – LIFA

Heilung – LIFA This issue’s cover is again from Pixabay. The artist is

This issue’s cover is again from Pixabay. The artist is  You can tell when I am fascinated by a book (or series), because, in addition to buying them in hardcover, I buy the ebooks because they are searchable, which makes it easier to check up on the various clever things the author has done.

You can tell when I am fascinated by a book (or series), because, in addition to buying them in hardcover, I buy the ebooks because they are searchable, which makes it easier to check up on the various clever things the author has done.

A return to the world of the Imperial Radch has been warmly welcomed by Ann Leckie fans everywhere. Personally I am particularly pleased that the new book, Translation State, focuses on the Presger, who are delightfully alien aliens.

A return to the world of the Imperial Radch has been warmly welcomed by Ann Leckie fans everywhere. Personally I am particularly pleased that the new book, Translation State, focuses on the Presger, who are delightfully alien aliens.

This is the fourth and final book in the Fallow Sisters series by Liz Williams. At one time Williams was muttering about there possibly being five books, but she has managed to wrap the series up in four and I think most fans will be pleased.

This is the fourth and final book in the Fallow Sisters series by Liz Williams. At one time Williams was muttering about there possibly being five books, but she has managed to wrap the series up in four and I think most fans will be pleased.

I very much enjoyed the first Miles Morales Spider-Man film, and was keen the see the new one in a cinema because I was expecting top notch animation. I was not disappointed. I don’t expect to see a better film this year.

I very much enjoyed the first Miles Morales Spider-Man film, and was keen the see the new one in a cinema because I was expecting top notch animation. I was not disappointed. I don’t expect to see a better film this year.

A new novel from Martha Wells is always interesting. A new novel in an entirely new setting is very exciting, because Wells creates such interesting worlds.

A new novel from Martha Wells is always interesting. A new novel in an entirely new setting is very exciting, because Wells creates such interesting worlds. I started this book a while back but put it down because it is rather slow to start. I got back into it because I was on a panel about the future of the family at Eurocon, and this is a book that definitely has thoughts in that direction.

I started this book a while back but put it down because it is rather slow to start. I got back into it because I was on a panel about the future of the family at Eurocon, and this is a book that definitely has thoughts in that direction.

I can’t believe that I haven’t reviewed this book. I’ve certainly talked about it enough. I’ve even interviewed Nicola Griffith about it for an LGBT+ History Month event. But there’s no actual review. I haven’t had time to re-read the book, but with Menewood due very soon now, here are some thoughts on its precursor.

I can’t believe that I haven’t reviewed this book. I’ve certainly talked about it enough. I’ve even interviewed Nicola Griffith about it for an LGBT+ History Month event. But there’s no actual review. I haven’t had time to re-read the book, but with Menewood due very soon now, here are some thoughts on its precursor.

This year’s Eurocon took place in Uppsala, a small city in Sweden just north of Stockholm. Arlanda airport is roughly equidistant between the two cities so Uppsala is an easy destination for international travelers. This year there was a problem with the train service between Arlanda and Uppsala, but there is an express bus service that does the job almost as well and is much cheaper.

This year’s Eurocon took place in Uppsala, a small city in Sweden just north of Stockholm. Arlanda airport is roughly equidistant between the two cities so Uppsala is an easy destination for international travelers. This year there was a problem with the train service between Arlanda and Uppsala, but there is an express bus service that does the job almost as well and is much cheaper. The Eurocon programming included a number of guided tours of the city and its environs. The one I immediately signed up for was to Gamla Uppsala, the site of the original Viking-era settlement which is about 5 km from the modern city. I’m very glad that I did.

The Eurocon programming included a number of guided tours of the city and its environs. The one I immediately signed up for was to Gamla Uppsala, the site of the original Viking-era settlement which is about 5 km from the modern city. I’m very glad that I did.

So there I was chatting away with a friend online while watching Glastonbury. We were watching different stages, and I happened to mention that The Pretenders were playing “Hymn to Her”, because how can you not when you have a song like that and are at Glastonbury. Then Katie says, “Have you heard of Heilung?”

So there I was chatting away with a friend online while watching Glastonbury. We were watching different stages, and I happened to mention that The Pretenders were playing “Hymn to Her”, because how can you not when you have a song like that and are at Glastonbury. Then Katie says, “Have you heard of Heilung?”

This is the May 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the May 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Infinity Gate

Infinity Gate When Women Were Dragons

When Women Were Dragons Hel’s Eight

Hel’s Eight The Terraformers

The Terraformers The Peripheral – Season 1

The Peripheral – Season 1 The Cleaving

The Cleaving Descendant Machine

Descendant Machine HistFest 2023

HistFest 2023 Celtic Wales

Celtic Wales 2023 Tolkien Lecture

2023 Tolkien Lecture Swansea ComicCon 2023

Swansea ComicCon 2023 Willow – the TV Series

Willow – the TV Series This issue’s cover is one of a series I will be running over the coming year. They are all pieces of art created by Iain J Clark for the Glasgow 2024 Worldcon. My thanks to Iain and to the Glasgow committee for giving me permission to use the art.

This issue’s cover is one of a series I will be running over the coming year. They are all pieces of art created by Iain J Clark for the Glasgow 2024 Worldcon. My thanks to Iain and to the Glasgow committee for giving me permission to use the art.

We have a new series from Mike Carey underway. Whereas the Rampart Trilogy was relatively near future, this one has strong space opera elements to it. The tag line on the cover of Infinity Gate reads, “The War for the Multiverse has Begun”. You can’t get a much bigger canvas than that.

We have a new series from Mike Carey underway. Whereas the Rampart Trilogy was relatively near future, this one has strong space opera elements to it. The tag line on the cover of Infinity Gate reads, “The War for the Multiverse has Begun”. You can’t get a much bigger canvas than that.

The basic premise of this book by Kelly Barnhill is very simple: when women get sufficiently angry about their lot in society, they turn into dragons. Sometimes they just fly away and have fun. Sometimes they eat their annoying husbands. And if said husbands have been sufficiently unpleasant, they probably incinerate them instead. That’s entirely reasonable, right?

The basic premise of this book by Kelly Barnhill is very simple: when women get sufficiently angry about their lot in society, they turn into dragons. Sometimes they just fly away and have fun. Sometimes they eat their annoying husbands. And if said husbands have been sufficiently unpleasant, they probably incinerate them instead. That’s entirely reasonable, right?

Listen up varmints, the old lady got something to tell ya.

Listen up varmints, the old lady got something to tell ya.

The important thing to know about Annalee Newitz’s fiction is that they are, first and foremost, a science writer. Thus what you get from them is old fashioned science fiction: speculative ideas explored for their potential, and spiced up for the reader by an adventure plot. We don’t see enough of that these days, so I’m glad that Newtiz is out there making books like this.

The important thing to know about Annalee Newitz’s fiction is that they are, first and foremost, a science writer. Thus what you get from them is old fashioned science fiction: speculative ideas explored for their potential, and spiced up for the reader by an adventure plot. We don’t see enough of that these days, so I’m glad that Newtiz is out there making books like this.

It has taken a while, but I have finally got around to watching Amazon’s adaptation of William Gibson’s The Peripheral. Those folks who insist that a TV version should never deviate in any way from the original book are doubtless furious about it, but it makes very good TV.

It has taken a while, but I have finally got around to watching Amazon’s adaptation of William Gibson’s The Peripheral. Those folks who insist that a TV version should never deviate in any way from the original book are doubtless furious about it, but it makes very good TV. Some books are more complicated to review than others. Regular readers will be well aware that The Cleaving is written by a very dear friend of mine, Juliet McKenna, many of whose books I publish. I am absolutely biased on the subject of her writing. Also I was born not far from Glastonbury, have read a lot of Arthuriana, and run a Pendragon campaign. The only reason that I haven’t written an Arthur book myself is that I’m not a good enough writer.

Some books are more complicated to review than others. Regular readers will be well aware that The Cleaving is written by a very dear friend of mine, Juliet McKenna, many of whose books I publish. I am absolutely biased on the subject of her writing. Also I was born not far from Glastonbury, have read a lot of Arthuriana, and run a Pendragon campaign. The only reason that I haven’t written an Arthur book myself is that I’m not a good enough writer.

Reviewers often have a good laugh at the nonsense publishers put into book blurbs. As a publisher myself, I see the issue from both sides, so I know why blurbs are what they are. Even so, I still often roll my eyes and how the description in a blurb can often bear little resemblance to the actual book. On the back of Gareth L Powell’s Descendant Machine, the good folks at Titan describe it as: “a gripping, fast-paced and brilliantly imagined science fiction thrill ride.” Reader, I could not have put it better myself.

Reviewers often have a good laugh at the nonsense publishers put into book blurbs. As a publisher myself, I see the issue from both sides, so I know why blurbs are what they are. Even so, I still often roll my eyes and how the description in a blurb can often bear little resemblance to the actual book. On the back of Gareth L Powell’s Descendant Machine, the good folks at Titan describe it as: “a gripping, fast-paced and brilliantly imagined science fiction thrill ride.” Reader, I could not have put it better myself.

This is a different sort of convention report. HistFest is a convention for fans of history books. It takes place in London, at the British Library no less, but is also available online through a streaming service. In addition to the event itself, HistFest, the organization, also offers online talks through the year, and I have presented a couple of those. Being part of the family, so to speak, I got a comped weekend pass to this year’s event.

This is a different sort of convention report. HistFest is a convention for fans of history books. It takes place in London, at the British Library no less, but is also available online through a streaming service. In addition to the event itself, HistFest, the organization, also offers online talks through the year, and I have presented a couple of those. Being part of the family, so to speak, I got a comped weekend pass to this year’s event. Those of you who read books about the ancient history of British Isles are probably already familiar with the name, Miranda Green. These days she is Miranda Aldhouse-Green and Professor Emerita in Archaeology at Cardiff University. Ray Howell is less well known on the popular history circuit, but he is a retired professor of Welsh Antiquity at the University of Wales. These are, in other words, two academic heavy hitters.

Those of you who read books about the ancient history of British Isles are probably already familiar with the name, Miranda Green. These days she is Miranda Aldhouse-Green and Professor Emerita in Archaeology at Cardiff University. Ray Howell is less well known on the popular history circuit, but he is a retired professor of Welsh Antiquity at the University of Wales. These are, in other words, two academic heavy hitters.

Getting to Oxford from South Wales is nowhere near as easy as it was from Wiltshire, especially as the Didcot-Oxford train line is now closed indefinitely. However, attending the annual Tolkien Lecture at Pembroke College requires an overnight stay, so I just planned to spend much of the two days travelling.

Getting to Oxford from South Wales is nowhere near as easy as it was from Wiltshire, especially as the Didcot-Oxford train line is now closed indefinitely. However, attending the annual Tolkien Lecture at Pembroke College requires an overnight stay, so I just planned to spend much of the two days travelling. There’s not a lot in the way of traditional SF&F conventions in Wales, but we do have a thriving and successful ComicCon in Swansea. It is currently housed in Swansea Arena, which also hosts pop concerts and the like. This year it overflowed into the sports hall of next-door LC2 (LC standing for Leisure Complex – LC2 also houses a swimming pool). As some people I know were exhibiting, I figured I should check it out. Roz, Jo and Chris came too.

There’s not a lot in the way of traditional SF&F conventions in Wales, but we do have a thriving and successful ComicCon in Swansea. It is currently housed in Swansea Arena, which also hosts pop concerts and the like. This year it overflowed into the sports hall of next-door LC2 (LC standing for Leisure Complex – LC2 also houses a swimming pool). As some people I know were exhibiting, I figured I should check it out. Roz, Jo and Chris came too.