Why yes, of course Barbie belongs here. It is about someone who travels from an imaginary world to the real world. How much more fantasy can you get?

Why yes, of course Barbie belongs here. It is about someone who travels from an imaginary world to the real world. How much more fantasy can you get?

So yes, in Greta Gerwig’s film, Barbie, a doll, ably assisted (or not) by her loyal boyfriend, Ken, travels to the real world to try to solve a problem that is making Barbieland less than perfect. Barbieland is, of course, that ideal world of the imagination in which all Barbie dolls (and Kens) exist. No one has to climb stairs, because a little girl can just pick you up and put you where you need to be. No one eats or drinks, though their homes are full of boxes, bottles and crockery. And, most importantly, no one has any genitals.

What could possibly go wrong?

Well, the primary source of discontent seems to be that a girl in the real world is having sad thoughts playing with her Barbie. This is bad, because it is Barbie’s job to make little girls happy. And because of this, things are starting to go wrong in Barbieland. Our heroine has discovered that her feet have gone flat, and therefore no longer fit perfectly and painlessly into high heels. Worse, her pristine plastic skin has started to develop blemishes that look suspiciously like cellulite!

Also, though this will only become an issue later, Ken is sad. Barbie is a doll for girls. In Barbieland, every night is Girls’ Night. While Ken sees himself as a fine figure of a man who might stand a chance with a girl as perfect as Barbie, she only sees him as a pleasant accessory. Ken is starting to grow up, and Barbie is still a girl.

At this point I should note that Barbieland is full of Barbies. Our heroine, played by Margot Robbie, is Stereotypical Barbie, but she has many friends. There’s President Barbie, Physicist Barbie, Famous Author Barbie, Doctor Barbie (played by Hari Ness) and many others. All of them are perfect, and they run Barbieland. There are many Kens too. They have nothing to do except admire the Barbies.

When things start to go wrong, Stereotypical Barbie is sent to see the great sage, Weird Barbie, beautifully embodied by Kate McKinnon. Weird Barbie is not perfect, but she does know a thing or two about getting to the real world. She sends Stereotypical Barbie on her way. Ken (Stereotypical Ken, that is), desperate to get the girl to notice him, tags along. And things go downhill from there.

There are a bunch of additional fine performances. I should have already mentioned the wonderfully sarcastic narration provided by Helen Mirren. Will Ferrell does a fine job as the CEO of Mattel. Simu Liu (previously famous as Shang Chi) out-dazzles Ryan Gosling as a rival Ken. Ncuti Gatwa has a Ken role as well, and as he’s now Doctor Who the possibilities for fanfic are endless. I was particularly pleased to see a staring role for America Ferrera that does not require her to be ugly. Indeed, as she (Gloria) and her daughter (Sasha) get to travel to Barbieland, they get to spend part of the film being impossibly gorgeous, because every woman in Barbieland is impossibly gorgeous (except Weird Barbie).

The film is very funny, or at least it is if you are female. Many of the jokes are at the expense of men and their obsessions. The Zack Snyder joke, in particular, will never cease to be hilarious to me.

Saying any more about the film would require serious spoilers and feminist critique. That will come, but before I need to scare away those of you who haven’t seen the film yet, I have one small complaint.

At the start of the film there is this brilliant 2001 pastiche in which we are told that, from the dawn of time, all dolls were babies intended to teach little girls the joys of motherhood. This supposedly changed when Barbie arrived. Reader, this is so not true.

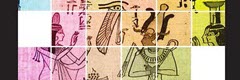

The first known doll-like figures are neolithic and we don’t know a lot about them as they were mostly organic and don’t survive well. There are doll-like figures from ancient Egypt, but they are basically just a shaped piece of wood with hair attached and it is hard to know what they were for. By the time of Classical Greece, however, little girls absolutely had articulated, humanoid female figures to play with. And reader, they were not babies. Let me introduce you to Warrior Princess Barbie.

Photo credit: Adrienne Mayor; the doll is from the 5th Century BCE and is currently in the Louvre.

Photo credit: Adrienne Mayor; the doll is from the 5th Century BCE and is currently in the Louvre.

Yes, girls from Classical Athens got to play with Amazon Warrior dolls. How wonderful is that? The whole baby thing didn’t start until around the middle of the 19th Century. It wasn’t actually the Victorians who were responsible, but rather their cousins in Germany and France. But of course the idea that little girls should play with toys that would equip them with the skills to become little wives quicky became popular in Britain and America too. Thank goodness we have mostly escaped from that.

And now…

********************************SPOILER ALERT!!!**************************************

I really recommend that you see this film unspoiled, but if you have seen it, or are unlikely to see it, read on.

When she arrives in the real world, Barbie discovers that the lot of women there is far from the perfection of Barbieland. Ken, meanwhile, discovers a concept called Patriarchy, and he rushes back to Barbieland to implement it there. Barbie has a lot of running away from Mattel goons to do. When she is finally rescued by Gloria and Sasha, and makes her way home, it is too late. Barbieland has become Kendom, and most of the Barbies have become simpering, brainless tarts who exist only to serve and adore their Kens. It is all very Joanna Russ.

Naturally there has to be a revolution. Weird Barbie is a key part of it as she’s not the sort of Barbie any Ken would want. Gloria is also able to help by explaining to the Barbies what life is like for women in the real world. But there is another character who is part of the revolution: Allan.

In Barbie mythology, Allan is Ken’s best friend. However (Grease allegory coming up), while Barbie and Ken are the perpetual Sandy and Danny of Barbieland, Allan is more like the guy Danny tried to pretend to be after seeing what Sandy was like in school. This isn’t in the film, but in Barbie history Allan married Barbie’s friend Midge, and they have a son in addition to Midge’s pregnant bump. Ken sees himself as an alpha male, whereas Allan is way down the pecking order. So far down that he succumbs to the dangers of matrimony. Russ would have had him as one of the Half-Changed.

In the film, Allan is played for laughs. I think this is sad, because Allan is basically an actual nice guy. He sees the Barbies as people. He respects them. And he knows full well that Patriarchy will be as much of a disaster for him as for them.

As I hinted earlier, much of the problem of Barbieland is that Ken sees himself as a man whereas Barbie still sees herself as a girl, albeit a woman-shaped one. Part of the message of the film seems to be that Barbie needs to grow up. I think that’s valid. It is all very well little girls being given positive role models, but unless they learn to cope with the real world (and the Patriarchy that infests it) they are not going to realise their dreams. Inevitably, learning to cope with it means learning to manage relationships with men.

And I do mean with men here, because Barbie is a very straight film. There is no Lesbian Barbie, and the perpetual Girls’ Night is just a slumber party. (There was once an Abby Wambach Barbie, but you couldn’t buy her.) The Kens might all look like refugees from the Village People, but they have only one thing on their minds, and that is Barbies. (They can’t think about their dicks because they don’t have any.)

However, while Barbie is very straight, it is not at all cis. One of the most talked about parts of the film is the end sequence where Barbie, having become human, visits a gynecologist, presumably to get herself a vagina. There are, of course, other explanations for this. When she became human I don’t see why her anatomy shouldn’t have followed suit. It is entirely possible that her visit to the doctor is about a pregnancy. But, given the jokes about her lack of genitals, her need to get a vagina seems a highly likely explanation. It also makes the ending one of pure transfeminine joy, seeing someone who desperately wants female genitals finally being on the brink of getting them.

The anti-trans lobby, of course, is also keen to see the trans-related ending, because it gives them an excuse to be outraged. They live for outrage.

The montage of (female) human life that Barbie sees before making the decision to become human is much more gender-essentialist, being basically all about family and raising children. It shouldn’t need to be pointed out that this is not the inevitable lot of human females, and that no one should be forced into it. However, our Barbie is a sovereign individual, and if that’s what attracts her to life as a human we shouldn’t criticize her for it. It is one of the things that is least available to her in Barbieland, after all. (There can be only one Pregnant Barbie, and Midge has that role.)

To my mind, however, the most trans part of the film occurs much earlier when Gloria is making her big speech about the lot of women. Towards the end she says this:

“And it turns out, in fact, that not only are you doing everything WRONG, but also, everything that happens is YOUR FAULT.”

I’d been nodding along with her throughout, because you can’t live as a woman in this world for 26 years (which I have) without getting a very good idea of the lot of womankind. That final line really hit home, because it is absolutely the lot of trans women. Everything we do we are told is wrong, and apparently all of the bad things in the world, specifically the bad things that are done by cis men, are our fault.

This, I think, explains a lot of the attraction of the anti-trans movement to a certain type of cis woman. They get to treat trans women the way that cis men treat them. It is a classic bullying victim reaction: if you can’t stand up to the bully, then you find someone even less fortunate than yourself and bully them in turn. And this is why it is pointless to use reason with transphobes. They know the things they are accusing us of aren’t true. They know that what they are doing causes hurt and distress. That’s the whole point. You don’t stop someone being a bully by telling them that being a bully is cruel, because being cruel is precisely what they want to do.

Barbie, thankfully, sees being cruel as bad. She’s as much on the side of trans girls as she is on the side of cis girls. Good for her. And you know, Barbie has come to the real world without Ken. He didn’t want to be human, and she decided that she didn’t need him. Maybe we’ve finally got a Lesbian Barbie after all.

This review is reprinted from Cheryl’s personal blog.

This review is reprinted from Cheryl’s personal blog.

This is the September 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the September 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Mammoths at the Gates

Mammoths at the Gates Tolkien, Race and Cultural History

Tolkien, Race and Cultural History The Man Who Fled the Nazis and Fought the Martians

The Man Who Fled the Nazis and Fought the Martians Follow Me: Religion in Fantasy & Science Fiction

Follow Me: Religion in Fantasy & Science Fiction Glorious Angels

Glorious Angels Where the Drowned Girls Go

Where the Drowned Girls Go What Moves the Dead

What Moves the Dead FantasyCon

FantasyCon Babylon 5: The Road Home

Babylon 5: The Road Home The Pleasure of Drowning

The Pleasure of Drowning Titans: Season 4

Titans: Season 4 Editorial – September 2023

Editorial – September 2023 It is that time of year again. Juliet McKenna has produced a new Green Man book. Pre-orders are open (

It is that time of year again. Juliet McKenna has produced a new Green Man book. Pre-orders are open (

No matter how much of a funk I am in about reading, nothing gets me rushing to my Kindle app faster than a new Nghi Vo Singing Hills novella. Nope, not even Murderbot. By the way, I say “Kindle” because getting hold of Tor.com novellas in the UK is expensive. I do want paper versions of these books eventually. And I am trying to remember to buy on Kobo or Weightless Books instead because that’s a good thing to do. The point is that when Mammoths at the Gates arrived, I dived straight in.

No matter how much of a funk I am in about reading, nothing gets me rushing to my Kindle app faster than a new Nghi Vo Singing Hills novella. Nope, not even Murderbot. By the way, I say “Kindle” because getting hold of Tor.com novellas in the UK is expensive. I do want paper versions of these books eventually. And I am trying to remember to buy on Kobo or Weightless Books instead because that’s a good thing to do. The point is that when Mammoths at the Gates arrived, I dived straight in.

One of the things that we have learned over the years about social media is that it has an almost total lack of nuance. Arguments rage, but they can never resolve because you can only ever be for or against a very simplistic position. Some of those arguments concern Tolkien. Was he a racist? Was he ‘just a man of his time’? Was he a great man whom none should dare question? These questions do not have simple answers. And this is where we can turn to academics for some in depth analysis.

One of the things that we have learned over the years about social media is that it has an almost total lack of nuance. Arguments rage, but they can never resolve because you can only ever be for or against a very simplistic position. Some of those arguments concern Tolkien. Was he a racist? Was he ‘just a man of his time’? Was he a great man whom none should dare question? These questions do not have simple answers. And this is where we can turn to academics for some in depth analysis.

It is somewhat dubious for me to review a book that I have an essay in, but I am very fond of the Academia Lunare series from Luna Press Publishing, so I want to encourage you to buy the books.

It is somewhat dubious for me to review a book that I have an essay in, but I am very fond of the Academia Lunare series from Luna Press Publishing, so I want to encourage you to buy the books.

This book came out in the UK in 2015. It being science fiction by a woman (and having a fair amount of sex in it), it did not get the promotion it deserved. Now, at last, there is a US edition, thanks to

This book came out in the UK in 2015. It being science fiction by a woman (and having a fair amount of sex in it), it did not get the promotion it deserved. Now, at last, there is a US edition, thanks to

Keeping a series going is a skill. Not all writers have it. Juliet McKenna has certainly got the knack as she keeps churning out Green Man books for me. Seanan McGuire, however, is a queen of series writing. Where the Drowned Girls Go is the seventh novella in the Wayward Children series, but that’s nothing; the October Daye series is already up to 15 full novels. I don’t know how she does it.

Keeping a series going is a skill. Not all writers have it. Juliet McKenna has certainly got the knack as she keeps churning out Green Man books for me. Seanan McGuire, however, is a queen of series writing. Where the Drowned Girls Go is the seventh novella in the Wayward Children series, but that’s nothing; the October Daye series is already up to 15 full novels. I don’t know how she does it.

My Hugo reading has suffered from my extreme busyness this month, but I have managed to get through the novellas. Even that has its challenges though. Read on.

My Hugo reading has suffered from my extreme busyness this month, but I have managed to get through the novellas. Even that has its challenges though. Read on.

FantasyCon was somewhat different for me this year. As I no longer have a car I can use to get books to conventions, I did not have a dealer table. I’ll be renting a car for BristolCon, because I’m doing a launch for the new Juliet McKenna book there, but I’m not sure how much dealer presence I will have at conventions in the future.

FantasyCon was somewhat different for me this year. As I no longer have a car I can use to get books to conventions, I did not have a dealer table. I’ll be renting a car for BristolCon, because I’m doing a launch for the new Juliet McKenna book there, but I’m not sure how much dealer presence I will have at conventions in the future. Well there’s a blast from the past. After all this time, who would have thought we’d get a new Babylon 5 story. Also, is it still good?

Well there’s a blast from the past. After all this time, who would have thought we’d get a new Babylon 5 story. Also, is it still good? In his blurb for this book, Peadar Ó Guilín describes Jean Bürlesk as, “a scoundrel and a charlatan.” He should perhaps have added that Bürlesk is a charming scoundrel and charlatan. He is also a professional tour guide, and thus used to telling stories. He has something of the gift of the gab, which is perhaps why an Irishman admires him so. Anyway, Bürlesk presented me with a copy of this book while we were in Uppsala for the Eurocon. He said he hopes to lure me to his mysterious homeland of Luxembourg, doubtless for nefarious purposes, though he insists that it is only for a convention.

In his blurb for this book, Peadar Ó Guilín describes Jean Bürlesk as, “a scoundrel and a charlatan.” He should perhaps have added that Bürlesk is a charming scoundrel and charlatan. He is also a professional tour guide, and thus used to telling stories. He has something of the gift of the gab, which is perhaps why an Irishman admires him so. Anyway, Bürlesk presented me with a copy of this book while we were in Uppsala for the Eurocon. He said he hopes to lure me to his mysterious homeland of Luxembourg, doubtless for nefarious purposes, though he insists that it is only for a convention.

DC’s attempts at doing television and movies are notoriously bad. I did like the Supergirl TV series, but I couldn’t motivate myself to watch much of the other series in that group. The only movies I’ve really liked are Wonder Woman (the first one), and Aquaman (for the giant war crabs, obviously). But there is a second group of DC shows that appear to exist in an entirely different part of the DC multiverse (and the various Superman shows may be a third reality). This group comprises Titans and Doom Patrol, and I quite like them. They are somewhat darker than the Arrowverse shows, and perhaps that makes them less silly.

DC’s attempts at doing television and movies are notoriously bad. I did like the Supergirl TV series, but I couldn’t motivate myself to watch much of the other series in that group. The only movies I’ve really liked are Wonder Woman (the first one), and Aquaman (for the giant war crabs, obviously). But there is a second group of DC shows that appear to exist in an entirely different part of the DC multiverse (and the various Superman shows may be a third reality). This group comprises Titans and Doom Patrol, and I quite like them. They are somewhat darker than the Arrowverse shows, and perhaps that makes them less silly.

This is the August 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the August 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Some Desperate Glory

Some Desperate Glory Barbie

Barbie The Coral Bones

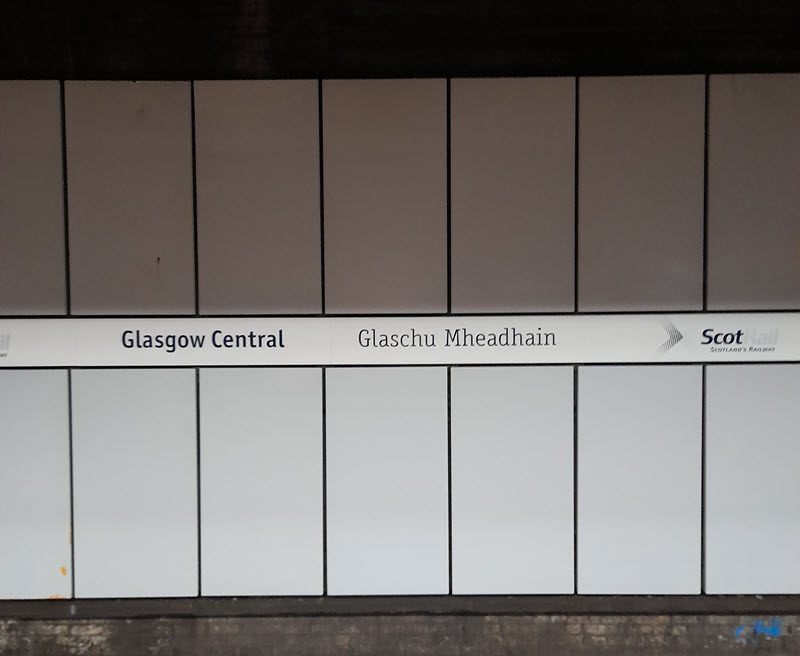

The Coral Bones Visiting Spaceport Glasgow

Visiting Spaceport Glasgow Guardians of the Galaxy – Volume 3

Guardians of the Galaxy – Volume 3 Even Though I Knew The End

Even Though I Knew The End Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh Strange New Worlds – Season 2

Strange New Worlds – Season 2 Begin Transmission

Begin Transmission Silures

Silures Secret Invasion

Secret Invasion This issue’s cover reproduces the art that Frank Wu made for the cover of Ion Trails, the in-flight magazine of the starship WSFS Armadillo. If you have no idea what that is all about, read the article on the Glasgow Worldcon site that appears in this issue.

This issue’s cover reproduces the art that Frank Wu made for the cover of Ion Trails, the in-flight magazine of the starship WSFS Armadillo. If you have no idea what that is all about, read the article on the Glasgow Worldcon site that appears in this issue.

The two novellas that Emily Tesh has out are fantasy. Her debut novel is space opera. Of course, depending on your view of such things, that might class as fantasy too, but it is certainly a very different thing. I was intrigued.

The two novellas that Emily Tesh has out are fantasy. Her debut novel is space opera. Of course, depending on your view of such things, that might class as fantasy too, but it is certainly a very different thing. I was intrigued.

Why yes, of course Barbie belongs here. It is about someone who travels from an imaginary world to the real world. How much more fantasy can you get?

Why yes, of course Barbie belongs here. It is about someone who travels from an imaginary world to the real world. How much more fantasy can you get? Photo credit: Adrienne Mayor; the doll is from the 5th Century BCE and is currently in the Louvre.

Photo credit: Adrienne Mayor; the doll is from the 5th Century BCE and is currently in the Louvre. This is a book that has been getting a lot of good press in the UK of late, not least because it was a finalist for this year’s Clarke Award. It didn’t win, but it was highly fancied and I can see why.

This is a book that has been getting a lot of good press in the UK of late, not least because it was a finalist for this year’s Clarke Award. It didn’t win, but it was highly fancied and I can see why.

We are now just under a year away from the next Glasgow Worldcon. A lot of excitement is building up on this side of the Atlantic. However, as is usual for a Worldcon, lots of people are keen to know more about the location. Obviously we had a Worldcon in Glasgow in 2005, but a lot can change in 18 years, and some of our 2024 members would not have been born then. As I had been asked to give a talk at the University of Glasgow this month, I took the opportunity to scout out the site and take a few pictures.

We are now just under a year away from the next Glasgow Worldcon. A lot of excitement is building up on this side of the Atlantic. However, as is usual for a Worldcon, lots of people are keen to know more about the location. Obviously we had a Worldcon in Glasgow in 2005, but a lot can change in 18 years, and some of our 2024 members would not have been born then. As I had been asked to give a talk at the University of Glasgow this month, I took the opportunity to scout out the site and take a few pictures.

There’s a theme going around social media these days that the Marvel Cinematic Universe is finished. There are, I think, legitimate reasons for thinking this: major stars wanting out, Jonathan Majors turning out to be an awful human being. But it doesn’t follow that all of the new content will be rubbish. Guardians of the Galaxy 3 has had some pretty terrible reviews. I don’t understand why.

There’s a theme going around social media these days that the Marvel Cinematic Universe is finished. There are, I think, legitimate reasons for thinking this: major stars wanting out, Jonathan Majors turning out to be an awful human being. But it doesn’t follow that all of the new content will be rubbish. Guardians of the Galaxy 3 has had some pretty terrible reviews. I don’t understand why. Somewhat later than usual, it is Hugo reading time. As is generally the case these days, the novella category is the hardest to judge. Normally voting for Nghi Vo would be easy, but the Adrian Tchaikovsky story is great too, and the Alix Harrow is a lot of fun. I have three to read, and this one was first on the list.

Somewhat later than usual, it is Hugo reading time. As is generally the case these days, the novella category is the hardest to judge. Normally voting for Nghi Vo would be easy, but the Adrian Tchaikovsky story is great too, and the Alix Harrow is a lot of fun. I have three to read, and this one was first on the list.

You are probably all at least vaguely familiar with the story of Gilgamesh. This, however, it not a review of the epic itself, but rather of one particular translation.

You are probably all at least vaguely familiar with the story of Gilgamesh. This, however, it not a review of the epic itself, but rather of one particular translation.

Two seasons in, and Strange New Worlds continues to be the most Trek-like of the Trek spin-offs. Once again it has a huge variety of episodes, while somehow managing to maintain a more-or-less coherent whole.

Two seasons in, and Strange New Worlds continues to be the most Trek-like of the Trek spin-offs. Once again it has a huge variety of episodes, while somehow managing to maintain a more-or-less coherent whole.  You are probably all aware of the idea that parts of the Matrix films are a trans allegory; the most famous example being that the red pill actually represents Premarin, a common form of estrogen medication back in the 20th Century. Just how much else there is in the films is open to question, but the thesis of Begin Transmission: The trans allegories of The Matrix by Tilly Bridges is that the entire film cycle (including the animated shorts and the fourth film) form one massive and intricately crafted allegory of trans life.

You are probably all aware of the idea that parts of the Matrix films are a trans allegory; the most famous example being that the red pill actually represents Premarin, a common form of estrogen medication back in the 20th Century. Just how much else there is in the films is open to question, but the thesis of Begin Transmission: The trans allegories of The Matrix by Tilly Bridges is that the entire film cycle (including the animated shorts and the fourth film) form one massive and intricately crafted allegory of trans life.

Back in issue #50 I ran a review of a small book called Celtic Wales, written by two very eminent historians who are experts on the country during the Iron Age. I found that book by chance in the local history section of Swansea Waterstones. As I happened to be back in the shop recently I had another look in that section to see if they had anything else. I was immediately rewarded.

Back in issue #50 I ran a review of a small book called Celtic Wales, written by two very eminent historians who are experts on the country during the Iron Age. I found that book by chance in the local history section of Swansea Waterstones. As I happened to be back in the shop recently I had another look in that section to see if they had anything else. I was immediately rewarded.

While I was happy to defend Guardians 3, I am much less enamoured of Marvel’s latest TV production. I’d been looking forward to something involving Nick Fury and the Skrulls. Sadly, what we got was a below par effort that tried to follow in the footsteps of The Falcon and the Winter Soldier and had some very obvious problems.

While I was happy to defend Guardians 3, I am much less enamoured of Marvel’s latest TV production. I’d been looking forward to something involving Nick Fury and the Skrulls. Sadly, what we got was a below par effort that tried to follow in the footsteps of The Falcon and the Winter Soldier and had some very obvious problems.

This is the July 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the July 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Menewood

Menewood Dragonfall

Dragonfall Good Omens – Season 2

Good Omens – Season 2 Nimona

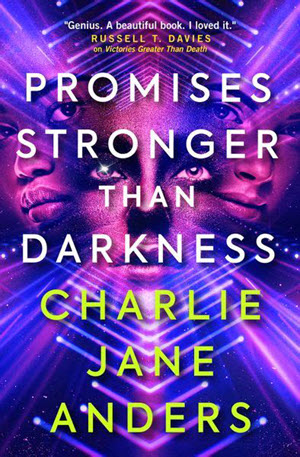

Nimona Promises Stronger Than Darkness

Promises Stronger Than Darkness Pemmi-Con

Pemmi-Con The Pemmi-Con Masquerade

The Pemmi-Con Masquerade Black Adam

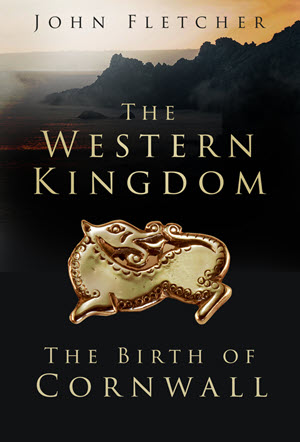

Black Adam The Western Kingdom

The Western Kingdom Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves This issue sees the second in my series of covers donated by Iain J Clark from the collection of images he has created for the Glasgow in 2024 Worldcon. This one is called “Sailing over Glasgow” and presumably celebrates the shipbuilding industry of the Clyde.

This issue sees the second in my series of covers donated by Iain J Clark from the collection of images he has created for the Glasgow in 2024 Worldcon. This one is called “Sailing over Glasgow” and presumably celebrates the shipbuilding industry of the Clyde.

Nicola Griffith’s foray into historical fiction, Hild, has been hugely successful. The book won a Lammy and was a finalist for a bunch of other major awards, including the Nebula, Otherwise and Campbell. (Yes, that Campbell which is an award for science fiction novels). Given that the book only covered the early years of the life of Hild of Whitby, a sequel was pretty much inevitable. Of course, with the amount of research that Griffith puts into these books, it wasn’t going to come quickly. However, Menewood is officially due on October 3rd. Griffith kindly sent me an ARC to look at.

Nicola Griffith’s foray into historical fiction, Hild, has been hugely successful. The book won a Lammy and was a finalist for a bunch of other major awards, including the Nebula, Otherwise and Campbell. (Yes, that Campbell which is an award for science fiction novels). Given that the book only covered the early years of the life of Hild of Whitby, a sequel was pretty much inevitable. Of course, with the amount of research that Griffith puts into these books, it wasn’t going to come quickly. However, Menewood is officially due on October 3rd. Griffith kindly sent me an ARC to look at.

Following an author’s career can tell you quite a bit about them as a person. Some writers who have achieved success seem content to keep pumping out what works each time, for less and less effort. Others are determined to stretch themselves with each new book and get better at their craft. L R Lam is definitely in the latter category.

Following an author’s career can tell you quite a bit about them as a person. Some writers who have achieved success seem content to keep pumping out what works each time, for less and less effort. Others are determined to stretch themselves with each new book and get better at their craft. L R Lam is definitely in the latter category.

As you probably all know, Gaiman and Pratchett had plans for a follow-up to Good Omens, but their careers took off so fast that neither of them had the time to make it happen. When the TV series was a success, Gaiman used those plans as the basis for a second series. Exactly what was in those plans is unknown, and doubtless fans will argue endlessly over it, but the important question is whether the resulting series lived up to the standards set by the first. Well reader, I was delighted with it.

As you probably all know, Gaiman and Pratchett had plans for a follow-up to Good Omens, but their careers took off so fast that neither of them had the time to make it happen. When the TV series was a success, Gaiman used those plans as the basis for a second series. Exactly what was in those plans is unknown, and doubtless fans will argue endlessly over it, but the important question is whether the resulting series lived up to the standards set by the first. Well reader, I was delighted with it. When I said that I did not expect to see a better film than Across the Spider-Verse this year, I really was not expecting to see another brilliant animated film just a couple of weeks later.

When I said that I did not expect to see a better film than Across the Spider-Verse this year, I really was not expecting to see another brilliant animated film just a couple of weeks later. Let us recap. The Unstoppable series by Charlie Jane Anders is space opera, but it is not your father’s space opera. Iain Banks would never have called a starship, Undisputed Training Bra Disaster. Nor, after successfully blowing an enemy starship to atoms, would a group of Culture heroes engage in a lengthy debate as to whether their actions were morally justified, and who should be held responsible for this war crime. Queer YA space opera is, in some ways, a very different beast.

Let us recap. The Unstoppable series by Charlie Jane Anders is space opera, but it is not your father’s space opera. Iain Banks would never have called a starship, Undisputed Training Bra Disaster. Nor, after successfully blowing an enemy starship to atoms, would a group of Culture heroes engage in a lengthy debate as to whether their actions were morally justified, and who should be held responsible for this war crime. Queer YA space opera is, in some ways, a very different beast.

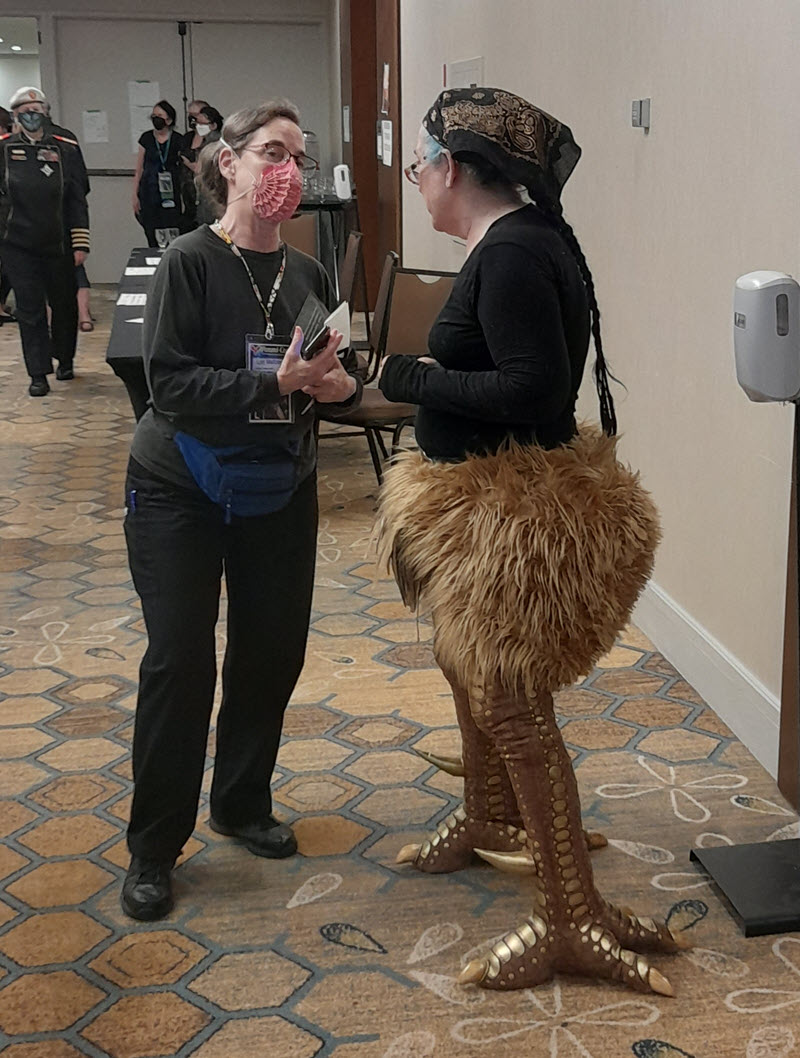

NASFics are strange beasts. It is sometimes said that running a NASFiC is rather like trying to run a Worldcon with half the money and half the attendees. I might also add half the volunteers to that. And, in the case of Pemmi-Con, “half” is probably a massive exaggeration on all counts.

NASFics are strange beasts. It is sometimes said that running a NASFiC is rather like trying to run a Worldcon with half the money and half the attendees. I might also add half the volunteers to that. And, in the case of Pemmi-Con, “half” is probably a massive exaggeration on all counts. Getting a quality masquerade from a convention with only just over 500 attendees is a challenging task, but somehow Sandy Manning managed it. There were a bunch of top quality costumers who came up from the USA and provided some master-level entries and judges, but it was particularly pleasing to have 4 young entrants, none of whom had ever been on stage before. Congratulations in particular to Turaga Vakama who used 3D printing to create what I assume was an anime costume.

Getting a quality masquerade from a convention with only just over 500 attendees is a challenging task, but somehow Sandy Manning managed it. There were a bunch of top quality costumers who came up from the USA and provided some master-level entries and judges, but it was particularly pleasing to have 4 young entrants, none of whom had ever been on stage before. Congratulations in particular to Turaga Vakama who used 3D printing to create what I assume was an anime costume.

This is another film that I watched on the plane on my way to Toronto. It being mostly superhero fight scenes, it doesn’t really warrant watching on a big screen, but it does have a lot more to the script than the Dungeons & Dragons film.

This is another film that I watched on the plane on my way to Toronto. It being mostly superhero fight scenes, it doesn’t really warrant watching on a big screen, but it does have a lot more to the script than the Dungeons & Dragons film. It might look like it from the cover, but this is not a fantasy novel. As the subtitle explains, The Western Kingdom is a history of the birth of the Kingdom of Cornwall, probably the oldest kingdom in the UK.

It might look like it from the cover, but this is not a fantasy novel. As the subtitle explains, The Western Kingdom is a history of the birth of the Kingdom of Cornwall, probably the oldest kingdom in the UK.