Well, what a month or so it has been. I’m not going to try to debunk all of the crazy that is happening out on social media, because frankly it has spiraled well out of my ability to play whack-a-mole. I will content myself with a couple of favourites. First up, it is not true that Kevin and I (and presumably Gary Wolfe as he was also a director of the Translation Awards) are the secret owners of the WSFS service marks. And secondly, the WSFS Mark Protection Committee is not laundering vast sums of money for China Telecom. Can we talk about more reasonable things, please?

Well, what a month or so it has been. I’m not going to try to debunk all of the crazy that is happening out on social media, because frankly it has spiraled well out of my ability to play whack-a-mole. I will content myself with a couple of favourites. First up, it is not true that Kevin and I (and presumably Gary Wolfe as he was also a director of the Translation Awards) are the secret owners of the WSFS service marks. And secondly, the WSFS Mark Protection Committee is not laundering vast sums of money for China Telecom. Can we talk about more reasonable things, please?

I should start by saying that I’m not going to go too much into what happened in China. I can’t read Chinese, and know very few people who can. I’m sure that there is a story to be told from the point of view of Chinese fans, but I’m very poorly placed to tell it. I’m going to concentrate mostly on the “where the fuck do we go from here?” question. My focus will be on trying to find a way forward that will minimize occurrences of Hugo Drama while maintaining an acceptable level of transparency, so that we can rebuild trust in the awards.

One thing that I think people need to do, is get a better idea of what is actually involved in Hugo Administration. On the one hand I have seen some folks claiming that the Hugos have been corrupt for years (and citing the fuss over Mary Robinette Kowal’s “The Lady Astronaut of Mars” novelette as proof). On the other hand some people are saying that this year’s situation is totally unprecedented because Hugo Administrators don’t normally rule anything as ineligible. If you want to know more about what goes on in the process of Hugo Administration, I highly recommend the Administrator Decisions report produced by Nicholas Whyte, Kathryn Duval and Brent Smart for the Helsinki Worldcon.

Sadly subsequent Worldcons have not matched this level of transparency. Partly I suspect that’s because it is too much work, and partly because it may have been deemed Too Much Information. Sadly the capacity of commenters on social media to find conspiracies in the most innocent decisions mitigates against transparency. However, I note that Nicholas Whyte has committed to doing something similar for Glasgow, which is a very good thing.

Of particular interest in the Helsinki report is the section numbered 3.9.4 on page 15. Here the authors talk about what happens when the E Pluribus Hugo system (EPH) determines that a finalist is ineligible and has to be removed. In order to keep the workload to sensible proportions, Hugo Administrators generally only make in-depth checks regarding eligibility for works/people who are likely finalists. You can’t know that until EPH has been run. As the authors note in this section, if one or more finalists is then removed, EPH is not then re-run in their absence. It occurs to me that this may explain some of the weirdness in the EPH data from Chengdu.

For a much more in-depth look at the issues with the EPH data from Chengdu, see this report by Camestros Felapton and Heather Rose Jones.

I don’t understand the EPH system well enough to comment further on how that might have affected the Chengdu results, but I continue to be of the belief that the EPH system, despite its obvious benefits, is too complex for awards with a transparent data policy because the data is so difficult to understand.

Moving on now to the future, I want to return to the discussion of how we can modify the Hugo Award process, and the method of governance of WSFS, to try to avoid a repeat of the Chengdu disaster. As part of this I’m going to cite blog posts by the Nerds of a Feather group, and by Abigail Nussbaum. I don’t mean to single them out for criticism. I’m using them as examples mainly because they have produced well-written blog posts that are easy to find, as opposed to commentary on social media which is a format notoriously lacking in nuance.

It is clear that many commentors still believe that a “WSFS Board” or similarly named body of people exists, either because they refer to it (witness this comment by Jonathan Cowie talking about the “WSFS board” on a post wherein I explicitly stated that no such body exists), or because they call for actions that can only be undertaken by such a body.

The Nerds of a Feather post, for example, calls for all of those people who participated in Hugo Administration to be forever banned from working on the Awards again. But how can this be enforced? Each Worldcon is a law unto itself. If it chooses to ignore a command from the WSFS Business meeting (BM), there is no accountability. In addition, Chris Garcia, in his personal addendum to the post, calls for the Mark Protection Committee (MPC) to remove all representatives of the Chengdu Worldcon and its Hugo Administration team from the MPC membership. There is no mechanism for this. Ordinary members of the MPC are appointed by the BM and can only be removed by the BM, or if they resign (which Dave McCarty did, but Ben Yalow did not). The Chengdu Worldcon is entitled to a representative of their choosing by dint of being a Worldcon. That’s baked into the Constitution.

There are also people calling for the Glasgow Worldcon to declare the Chengdu Hugos null and void, and to re-run the vote. Glasgow has no power to do any such thing. Can you imagine the chaos there would be if individual Worldcons had the power to overturn the results of the Hugos from their predecessors? And please don’t tell me that they would only use such powers for good. The last few years of US and UK politics should have taught us what happens when you rely on tradition and convention to ensure that people don’t do anything bad.

The point here is that if we spend our time demanding things that either cannot be done, or cannot be enforced, this will not help the Hugos. Indeed, it will reduce confidence in them, because people will see action being demanded, and that action not happening. It will lead to more people asking why the “WSFS Board” has not done what is asked of them, from people who are unaware that the “WSFS Board” does not exist.

Nussbaum, to her credit, spotted this problem, but the only solution she could suggest was direct action by fandom through things like a boycott of Worldcon. Aside from the fact that this sounds disturbingly like mob rule, the trouble with it as a general solution is that problems often only come to light when it is too late. We can’t punish Chengdu by boycotting Glasgow.

Some people have pointed to the existence of something called Worldcon Intellectual Property (WIP). This is non-profit organization that was set up to be the legal owner of the WSFS service marks because the authorities around the world that deal with registering service marks don’t like dealing with unincorporated organizations. In theory, WIP’s membership is identical to that of the MPC, and it too is subservient to the Business Meeting.

Some people who are keen to see Ben Yalow punished have suggested the WIP could change its bylaws to allow it to expel directors. This may be possible, but consider what this would mean if it is.

Firstly there is no guarantee that Yalow would be kicked off. Remember that the MPC is made up of SMOFs who have known Yalow for years. The vote to censure him was only 8-5, and boards of directors are generally less wiling to hand out punishment if it is more than a slap on the wrist. My guess is that if WIP did decide that it could kick people out, the first person to go would be Kevin, because he keeps insisting that WIP should be subservient to the Business Meeting.

But if WIP does give itself the power to remove directors without reference to the BM, it can presumably give itself the power to appoint them too. And that would mean that membership of the WIP board could no longer be controlled by the WSFS membership. As owners of the WSFS marks, they could presumably also create a body to administer the Hugos separate from Worldcons, and decide whether a convention could call itself Worldcon. These are both things that people on social media have been calling for, but that power would be vested in a group of SMOFs that WSFS members no longer have any influence over (including Ben Yalow and four of his good friends). I submit that this is not actually the outcome that people want.

What I think we need to look at here is a change in the method of governance of WSFS, so that when something goes wrong there is a possibility of action being taken well before the next Business Meeting, and a possibility of those who have done wrong being held to account by the membership in some way. There are, broadly, four options.

1. Dave McCarty has advocated keeping the current system whereby individual Worldcons are a law unto themselves and cannot be held responsible for their actions. That, of course, is what someone who has been a Worldcon chair might be expected to say. I suspect that significant numbers of people in the Worldcon-running community agree with him. It is in their interests not to be able to be held to account.

2. We change the WSFS Business Meeting in some way so as to make it more able to react quickly in cases of crisis, and more able to hold Worldcons to account. This includes suggestions that it be held online at times other than during Worldcon.

3. We allow the current directors of WIP to effectively stage a legal coup and take control of WSFS away from the membership.

4. We switch to a representative system of governance.

The final option requires a bit of explanation. Broadly speaking, a democracy can either be participatory or representative. In a participatory democracy the individual members of the community all have a voice in how decisions are taken. The WSFS Business Meeting is a system of participatory democracy. All WSFS members are, at least in theory, able to attend the BM and to vote on how WSFS should act. It is based in part on ideas about governance explored in Heinlein’s novel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, which in turn was inspired by the Town Hall Meeting system of government adopted by some of the early American pioneers, which in turn was inspired by the method of government used in Classical Athens.

It should be noted that in Athens only adult male citizens were allowed to vote, and the USA no longer uses participatory democracy at state or federal level. Even when it is used at town level, it is sometimes only used to elect people who will then to the day-to-day running of the town.

In contrast a representative democracy allows for the election of a group of people who handle the day-to-day business of government. Ordinary citizens participate directly only in elections, in referenda if they are allowed, and possibly in recall motions if an individual representative has done something very bad. They may, of course, lobby their representative to behave in particular ways.

Most nation states are (or at least pretend to be) representative democracies, but many other organisations use a similar approach. SFWA, for example, is a representative democracy, because the officers of the Association (who do much of the work of running it) are elected by the members.

Participatory democracies have problems. The first is that, the larger the group becomes, the harder meetings become to manage. Everyone supposedly has a right to be heard, and that’s a lot harder if you have 3000 members than if you have only 30. You end up adopting some sort of formal set of rules for conducting meetings, such as Roberts Rules of Order, which are traditionally used for the BM. And then you run into trouble with people who study the rules so as to be able to use them to their advantage.

Some people (Nussbaum included) have called for WSFS to get rid of Roberts. But you can’t just run a big meeting without rules. Every parliament in the world knows that. There may be an existing set of rules that would be easier for people to understand and learn that we could use instead, as Nussbaum suggests, but the idea that fandom could somehow come up with a new set of meeting rules that are superior to any previously developed is, I’m afraid, ‘Fans are Slans’ nonsense.

This Wikipedia article on the concept of town meetings also has a section on democratic theory. I draw your attention to the claims that large meetings of this type tend to favour those who are self-confident and well-educated, while disadvantaging those who are less able to put their arguments across. That would be a major issue in an international organization where some members are not native English speakers. It is also a major issue for neurodiverse people.

Another problem with participatory democracies is that they are easily undermined by bad actors. Exploiting the rules of parliamentary procedure is only one such trick. Meetings can be held at inconvenient times and in inconvenient places so as to discourage most members from turning up. (This is true of the existing BM.) You can gum up the works by talking on and on, and by introducing endless, pointless procedural motions so that most people get bored and leave. You can insist that important issues must be adopted by consensus, and then refuse to compromise on anything. You can demand that any vote you lost be reconsidered at the next meeting because you claim the original vote was invalid. The objective is to make participation in the meeting so unpleasant than only your own extremist faction will have the patience to stay to the end and win the vote.

In addition, a participatory democracy is vulnerable to what is called the ‘Tyranny of the Majority’. For example, if most of the attendees at the WSFS BM are white Americans, you might expect their decisions to be biased in favour of the interests of white Americans. (The vast majority of the existing directors of WIP are white Americans).

Back in 2022, Kevin proposed a system of elected government for WSFS. You can find it here. It was more of a discussion document than a fully fledged proposal, but in any case it went down like a lead balloon with fandom.

In theory, representative democracies are intended to solve a lot of the issues with participatory democracies. Ordinary members don’t have to spend a lot of time in meetings, and don’t have to learn complex rules of parliamentary procedure. They rely on their representatives to do that. And if the representatives don’t do what they want, they can be voted out, or even recalled. So why don’t we have one for WSFS?

Back in the early days of WSFS, there was a proposal to turn the society into a corporation and elect a board of directors. That idea was voted down, primarily because fans didn’t trust anyone else to run WSFS on their behalf. Now we face a major crisis of confidence in WSFS, and a seeming demand for a strong authority than can hold Worldcons to account. But are we seeing discussion of new methods of governance for the Society? No, what we are seeing is people calling for the Business Meeting to be held online on a regular basis so that everyone can have their say.

People, this is exactly the same attitude that got us into this mess. If you keep insisting that you will not trust anyone else to run WSFS on your behalf, then we will continue to end up with no one running it, and Worldcons free to behave however they want without consequence. Or WIP will manage to extricate itself from control by the BM.

Now you may say that if we have elected representatives then the SMOFs will still end up running WSFS, because they are the only ones who will run for office. That’s probably true. But they would be SMOFs who had been elected by popular vote, and might be subject to recall if they misbehaved, rather than SMOFs elected by the Business Meeting that we then can’t easily hold to account.

So what people should be doing now is discussing what form of representative government they want, and how it should be constituted. Do we want a board of directors (i.e. WIP but somehow under the control of WSFS members), or a large Council of WSFS such as the idea Kevin floated? Do we want representation from outside of the Anglophone world baked in so as to encourage a move towards a more international community? Do we want to require important changes to the Constitution to be subject to popular ratification by a vote of all members? Do we want to be able to recall members of the governing body who misbehave?

There are, I am sure, people out there who know much more about systems of governance than me who could weigh in with suggestions. I don’t claim to have the answers. But I am convinced that, unless we start to think seriously about this, the opportunity to effect change at the Glasgow Business Meeting will pass us by, and we will once again be locked into the cycle of disaster and outrage that has been all too typical of Worldcon and the Hugos for the past few decades. Or worse, the directors of WIP will find a legal way to wrest control of WSFS from the Business Meeting and we will never have a say in how the Society is run again.

If you followed me on Twitter, back in the days when it was not just a propaganda tool for fascists, you may well have seen me retweet posts by the Museum Bums account. Well they were funny. Also I had a personal connection. I’ve known Mark Small for many years via OutStories Bristol. He and Jack Shoulder were clearly having a lot of fun with their account. And because fun sells, that account is now a book too.

If you followed me on Twitter, back in the days when it was not just a propaganda tool for fascists, you may well have seen me retweet posts by the Museum Bums account. Well they were funny. Also I had a personal connection. I’ve known Mark Small for many years via OutStories Bristol. He and Jack Shoulder were clearly having a lot of fun with their account. And because fun sells, that account is now a book too.

Because of the connection with The Library of Broken Worlds, I decided that I should finally get around to watching Spirited Away. It is on Netflix, after all. I realise that I am very late to this and I’m assuming that almost everyone reading this has already seen the film.

Because of the connection with The Library of Broken Worlds, I decided that I should finally get around to watching Spirited Away. It is on Netflix, after all. I realise that I am very late to this and I’m assuming that almost everyone reading this has already seen the film.

This is the February 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the February 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Dawnhounds

The Dawnhounds The Imposition of Unnecessary Obstacles

The Imposition of Unnecessary Obstacles The Four Deaths and One Resurrection of Fyodor Mikhailovich

The Four Deaths and One Resurrection of Fyodor Mikhailovich The Last to Drown

The Last to Drown The Meat Tree

The Meat Tree Chengdu Revisited

Chengdu Revisited What If? – Season #2

What If? – Season #2 Masters of the Universe: Revolution

Masters of the Universe: Revolution Percy Jackson and the Olympians

Percy Jackson and the Olympians Editorial – February 2024

Editorial – February 2024 We are back with Pixabay for this issue’s cover. The art is by

We are back with Pixabay for this issue’s cover. The art is by

Update: This review has been corrected for pronouns because the “About the Author” section in the book is out of date. I have a sneaking suspicion that I should have known this, but I’m old and the memory is not what it was. Anyway, I’m now even more happy that I loved the book.

Update: This review has been corrected for pronouns because the “About the Author” section in the book is out of date. I have a sneaking suspicion that I should have known this, but I’m old and the memory is not what it was. Anyway, I’m now even more happy that I loved the book.

As you have probably noticed, the big trend in genre publishing these days is ‘cozy’. Books are getting marketed as ‘cozy’ even if they are anything but. Allegedly the world is now such a scary place, that only warm and unchallenging fiction will sell. I see the point. Sean McMullen’s Generation Nemesis is a brutal examination of just how awful a post-climate-collapse world might be. I really like the book, but it is not selling as well as I’d hoped. At Eastercon last year people straight up told me that they didn’t want to read anything that was depressing.

As you have probably noticed, the big trend in genre publishing these days is ‘cozy’. Books are getting marketed as ‘cozy’ even if they are anything but. Allegedly the world is now such a scary place, that only warm and unchallenging fiction will sell. I see the point. Sean McMullen’s Generation Nemesis is a brutal examination of just how awful a post-climate-collapse world might be. I really like the book, but it is not selling as well as I’d hoped. At Eastercon last year people straight up told me that they didn’t want to read anything that was depressing.

A new book from Zoran Živković is always welcome here, though the latest one does take me a little out of my comfort zone. It is called The Four Deaths and One Resurrection of Fyodor Mikhailovich, and the Fyodor Mikhailovich of the title is, of course, the man better known to Westerners as Dostoevsky. Živković is fond of books that comprise several short stories with a linking theme, which he calls “mosaic novels” rather than “fixups”, a much nicer title. This book comprises four stories, and poor Dostoevsky dies in all of them.

A new book from Zoran Živković is always welcome here, though the latest one does take me a little out of my comfort zone. It is called The Four Deaths and One Resurrection of Fyodor Mikhailovich, and the Fyodor Mikhailovich of the title is, of course, the man better known to Westerners as Dostoevsky. Živković is fond of books that comprise several short stories with a linking theme, which he calls “mosaic novels” rather than “fixups”, a much nicer title. This book comprises four stories, and poor Dostoevsky dies in all of them.

I’ve been meaning to get to Lorraine Wilson’s work for some time because it has been clear from the way she’s getting reviewed by others that she’s a special talent. Having a book of hers in the Luna Press novella series was a perfect opportunity. And it turns out that my esteemed colleagues are dead right about her ability.

I’ve been meaning to get to Lorraine Wilson’s work for some time because it has been clear from the way she’s getting reviewed by others that she’s a special talent. Having a book of hers in the Luna Press novella series was a perfect opportunity. And it turns out that my esteemed colleagues are dead right about her ability.

Gwyneth Lewis is not the sort of writer who normally features in these pages. She’s primarily a poet, and her achievements include being made the inaugural National Poet of Wales in 2005, and winning the Bardic Crown at the 2012 National Eisteddfod. (The Crown is awarded for free verse, as opposed to the better known Chair which is for a long poem in strict metre.) If you have ever been to Cardiff, the words inscribed on the roof of the Millennium Centre were written by her. That’s serious mainstream literary credibility.

Gwyneth Lewis is not the sort of writer who normally features in these pages. She’s primarily a poet, and her achievements include being made the inaugural National Poet of Wales in 2005, and winning the Bardic Crown at the 2012 National Eisteddfod. (The Crown is awarded for free verse, as opposed to the better known Chair which is for a long poem in strict metre.) If you have ever been to Cardiff, the words inscribed on the roof of the Millennium Centre were written by her. That’s serious mainstream literary credibility.

Well, what a month or so it has been. I’m not going to try to debunk all of the crazy that is happening out on social media, because frankly it has spiraled well out of my ability to play whack-a-mole. I will content myself with a couple of favourites. First up, it is not true that Kevin and I (and presumably Gary Wolfe as he was also a director of the Translation Awards) are the secret owners of the WSFS service marks. And secondly, the WSFS Mark Protection Committee is not laundering vast sums of money for China Telecom. Can we talk about more reasonable things, please?

Well, what a month or so it has been. I’m not going to try to debunk all of the crazy that is happening out on social media, because frankly it has spiraled well out of my ability to play whack-a-mole. I will content myself with a couple of favourites. First up, it is not true that Kevin and I (and presumably Gary Wolfe as he was also a director of the Translation Awards) are the secret owners of the WSFS service marks. And secondly, the WSFS Mark Protection Committee is not laundering vast sums of money for China Telecom. Can we talk about more reasonable things, please? The first social media post I saw about the new season of What If? said that it was much worse than season 1. The second one said it was much better. Needless to say, the truth is somewhat in between.

The first social media post I saw about the new season of What If? said that it was much worse than season 1. The second one said it was much better. Needless to say, the truth is somewhat in between. It is a source of amazement to me that a toy franchise, which is what Masters of the Universe is, manages to give rise to so many inventive re-workings. We’ve had the magnificent She-Ra and the Princesses of Power series, and more recently two competing Masters of the Universe series. There is no canon. All of these series exist entirely in their own part of the multiverse.

It is a source of amazement to me that a toy franchise, which is what Masters of the Universe is, manages to give rise to so many inventive re-workings. We’ve had the magnificent She-Ra and the Princesses of Power series, and more recently two competing Masters of the Universe series. There is no canon. All of these series exist entirely in their own part of the multiverse. I’d enjoyed the one Rick Riordan book I have read (Magnus Chase and the Hammer of Thor, featuring a gender-fluid child of Loki), so when I saw a Percy Jackson series pop up on Disney+ I was interested. Then some of my Classicist friends started saying good things about it, so it moved up the watch list.

I’d enjoyed the one Rick Riordan book I have read (Magnus Chase and the Hammer of Thor, featuring a gender-fluid child of Loki), so when I saw a Percy Jackson series pop up on Disney+ I was interested. Then some of my Classicist friends started saying good things about it, so it moved up the watch list.

December 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

December 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. A Midwinter’s Tail

A Midwinter’s Tail Scavengers Reign

Scavengers Reign Doctor Who: The Return of Russellon

Doctor Who: The Return of Russellon The History of the Welsh Dragon

The History of the Welsh Dragon Bookshops and Bonedust

Bookshops and Bonedust Normal Women

Normal Women Mythical Creatures

Mythical Creatures The Celts on Amazon Prime

The Celts on Amazon Prime Once again it is time to use a piece of art by the very wonderful Iain J Clark on the cover. This is the time of year when trees feature heavily in the seasonal mythology, so I thought this piece would be perfect. As well as being a lovely tree, it also features the Hugo rocket, to remind you that the Glasgow Worldcon is not far away now, which is the primary purpose of running these images.

Once again it is time to use a piece of art by the very wonderful Iain J Clark on the cover. This is the time of year when trees feature heavily in the seasonal mythology, so I thought this piece would be perfect. As well as being a lovely tree, it also features the Hugo rocket, to remind you that the Glasgow Worldcon is not far away now, which is the primary purpose of running these images.

Ah yes, it is that time of year when the entertainment industry pumps out vast quantities of soppy seasonal material. I’ve never felt any particular desire to watch Hallmark Christmas movies, or any other Christmas movie for that matter (and yes, that does include Die Hard). So what on Earth tempted me to pick up a copy of A Midwinter’s Tail by Lili Hayward?

Ah yes, it is that time of year when the entertainment industry pumps out vast quantities of soppy seasonal material. I’ve never felt any particular desire to watch Hallmark Christmas movies, or any other Christmas movie for that matter (and yes, that does include Die Hard). So what on Earth tempted me to pick up a copy of A Midwinter’s Tail by Lili Hayward?

Russell T Davies sure knows how to make an entrance. Also he is not afraid to upset people, particularly the pro-bigotry brigade. How he gets away with this on the BBC I do not know, but I’m very glad he does.

Russell T Davies sure knows how to make an entrance. Also he is not afraid to upset people, particularly the pro-bigotry brigade. How he gets away with this on the BBC I do not know, but I’m very glad he does. This past month I have experienced two supposed histories of the dragon in the UK, neither of which made any reference to the one part of the country that actually has a dragon on its flag. One was a History Hit documentary from Jasmine Elmer (whom I met at HistFest earlier this year). The other was an episode of Rhianna Pratchett’s Mythical Creatures, reviewed elsewhere in this issue. This doesn’t surprise me. “British” history, as it is taught in English schools, and portrayed in the English media, tends to ignore Wales entirely unless it is being conquered by the English. Also a lot of the sources are in mediaeval Welsh which is rarely studied outside of Wales. But the story of why there is a dragon on the Welsh flag is interesting, so I’m making a stab at telling it.

This past month I have experienced two supposed histories of the dragon in the UK, neither of which made any reference to the one part of the country that actually has a dragon on its flag. One was a History Hit documentary from Jasmine Elmer (whom I met at HistFest earlier this year). The other was an episode of Rhianna Pratchett’s Mythical Creatures, reviewed elsewhere in this issue. This doesn’t surprise me. “British” history, as it is taught in English schools, and portrayed in the English media, tends to ignore Wales entirely unless it is being conquered by the English. Also a lot of the sources are in mediaeval Welsh which is rarely studied outside of Wales. But the story of why there is a dragon on the Welsh flag is interesting, so I’m making a stab at telling it. Being nomads, the Sarmatians probably brought their families with them, so that was a sizeable influx of steppe horse people into Britain. I’ve seen estimates of as many as 20,000 people.

Being nomads, the Sarmatians probably brought their families with them, so that was a sizeable influx of steppe horse people into Britain. I’ve seen estimates of as many as 20,000 people.  Mention of Geoffrey of Monmouth brings us to the famous prophecy of Merlin concerning the red and white dragons that are fighting for the future of Britain. The story also appears in the tale of Lludd & Llefelys from the Mabinogion, but Geoffrey’s work is older than any surviving Welsh-language source. This story took on particular significance during the Wars of the Roses, in which one side had a red badge and the other white. Interestingly, Edward IV claimed descent from Cadwaladr, but the Tudors had a far more believable claim. The Tudor ancestral home was the village of Penmynydd (Mountain Top) on Anglesey. Henry Tudor used a red dragon on his coat of arms to denote his descent from Cadwalladr.

Mention of Geoffrey of Monmouth brings us to the famous prophecy of Merlin concerning the red and white dragons that are fighting for the future of Britain. The story also appears in the tale of Lludd & Llefelys from the Mabinogion, but Geoffrey’s work is older than any surviving Welsh-language source. This story took on particular significance during the Wars of the Roses, in which one side had a red badge and the other white. Interestingly, Edward IV claimed descent from Cadwaladr, but the Tudors had a far more believable claim. The Tudor ancestral home was the village of Penmynydd (Mountain Top) on Anglesey. Henry Tudor used a red dragon on his coat of arms to denote his descent from Cadwalladr.  Based on reading Legends & Lattes, I was pretty sure that I knew what to expect from the next Travis Baldree book. It would be a quick read, unchallenging, heartwarming, and likely to make you hungry. Reader, I was not surprised in any way.

Based on reading Legends & Lattes, I was pretty sure that I knew what to expect from the next Travis Baldree book. It would be a quick read, unchallenging, heartwarming, and likely to make you hungry. Reader, I was not surprised in any way.

For whose who don’t know, Phillipa Gregory is one of the most successful writers of historical fiction in the UK. She specializes mainly in mediaeval and Tudor times, but her novel about the slave trade, A Respectable Trade, is memorialized on a plaque in Bristol Docks and was, for a long time, the city’s only public memorial to that shameful part of its history. I think Marvin Rees has done something about that now, but I am a bit out of date.

For whose who don’t know, Phillipa Gregory is one of the most successful writers of historical fiction in the UK. She specializes mainly in mediaeval and Tudor times, but her novel about the slave trade, A Respectable Trade, is memorialized on a plaque in Bristol Docks and was, for a long time, the city’s only public memorial to that shameful part of its history. I think Marvin Rees has done something about that now, but I am a bit out of date.

As far as I’m aware, most of Rhianna Pratchett’s career so far has been in video games, which I dont play because I’m completely useless at them. In her position, I’d probably run as far away from the parental profession as possible. These days, however, she seems open about claiming the label of Fantasy Writer, and part of that has been to helm a series for BBC Radio 4 called Mythical Creatures.

As far as I’m aware, most of Rhianna Pratchett’s career so far has been in video games, which I dont play because I’m completely useless at them. In her position, I’d probably run as far away from the parental profession as possible. These days, however, she seems open about claiming the label of Fantasy Writer, and part of that has been to helm a series for BBC Radio 4 called Mythical Creatures. It used to be the case that there was never anything worth watching on TV over the holidays. That’s no longer true, because now we have a ton of streaming services all groaning under the weight of content more varied and potentially interesting than any Christmas dinner table. Even someone of my relatively limited tastes in TV can be guaranteed to find something worth checking out.

It used to be the case that there was never anything worth watching on TV over the holidays. That’s no longer true, because now we have a ton of streaming services all groaning under the weight of content more varied and potentially interesting than any Christmas dinner table. Even someone of my relatively limited tastes in TV can be guaranteed to find something worth checking out.

This is the November 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the November 2023 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Jinn-Bot of Shantiport

The Jinn-Bot of Shantiport System Collapse

System Collapse A Fire Born of Exile

A Fire Born of Exile My Brother’s Keeper

My Brother’s Keeper Fantasy at the British Library

Fantasy at the British Library The Marvels

The Marvels Spirit

Spirit This is Not a Grail Romance

This is Not a Grail Romance Silver on the Tree

Silver on the Tree Masques of the Disappeared

Masques of the Disappeared Loki – Season #2

Loki – Season #2 Lower Decks – Season #4

Lower Decks – Season #4 This issue’s cover art is titled, “soldier”, but I like to think that it is actually Murderbot. And yes, the new Murderbot book is reviewed in this issue.

This issue’s cover art is titled, “soldier”, but I like to think that it is actually Murderbot. And yes, the new Murderbot book is reviewed in this issue.

The new novel from Samit Basu is billed as a science fiction version of Aladdin, which it is, but it is also so much more.

The new novel from Samit Basu is billed as a science fiction version of Aladdin, which it is, but it is also so much more.

A new Murderbot book is always a delight and, even though this one was a novel, I tore through it in a day. It is, as you would expect, highly entertaining. But by now a Murderbot book has to advance the story, which is what I will be focusing on here.

A new Murderbot book is always a delight and, even though this one was a novel, I tore through it in a day. It is, as you would expect, highly entertaining. But by now a Murderbot book has to advance the story, which is what I will be focusing on here.

The latest Xuya universe novel from Aliette de Bodard is billed as inspired by The Count of Monte Cristo. It is less of a re-telling than Gwyneth Jones’s excellent Spirit (my review of which is re-printed in this issue), but the story definitely benefits from the inspiration.

The latest Xuya universe novel from Aliette de Bodard is billed as inspired by The Count of Monte Cristo. It is less of a re-telling than Gwyneth Jones’s excellent Spirit (my review of which is re-printed in this issue), but the story definitely benefits from the inspiration.

Hallowe’en has come and gone for another year, and what better way to mark the season than with a novel about terrifying supernatural goings-on on the Yorkshire Moors, staring none other than Emily Brontë?

Hallowe’en has come and gone for another year, and what better way to mark the season than with a novel about terrifying supernatural goings-on on the Yorkshire Moors, staring none other than Emily Brontë?

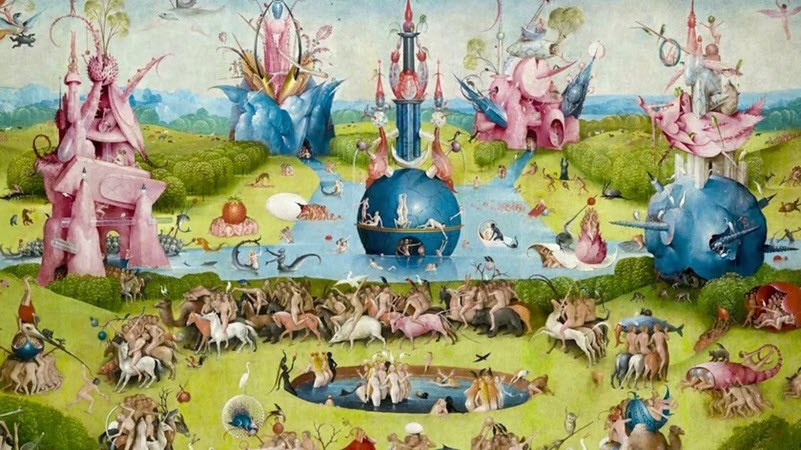

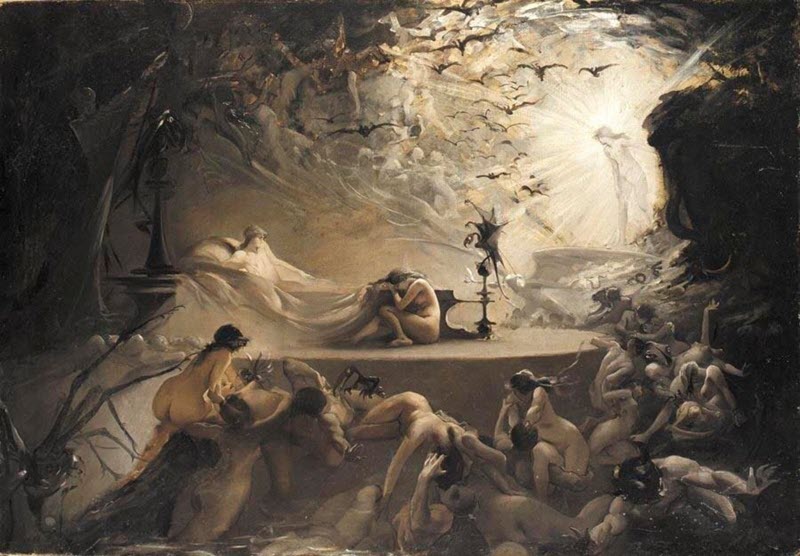

The British Library recently opened a major new exhibition titled, Fantasy: Realms of Imagination. If you can get to London, it is well worth a look. As I was in town anyway for Judith Clute’s book launch, I popped in to take a look.

The British Library recently opened a major new exhibition titled, Fantasy: Realms of Imagination. If you can get to London, it is well worth a look. As I was in town anyway for Judith Clute’s book launch, I popped in to take a look. Captain Marvel is one of my favorite productions from the MCU, and I loved the Ms Marvel TV series, so I have been eagerly awaiting the movie in which Carol Danvers and Kamala Khan finally get to meet. The addition of Monica Rambeau, whom we first met as a young girl in Captain Marvel, is an added bonus.

Captain Marvel is one of my favorite productions from the MCU, and I loved the Ms Marvel TV series, so I have been eagerly awaiting the movie in which Carol Danvers and Kamala Khan finally get to meet. The addition of Monica Rambeau, whom we first met as a young girl in Captain Marvel, is an added bonus. This review was first published on Cheryl’s personal blog in March 2009. It is reprinted here to accompany the review of A Fire Born of Exile as both books are inspired by The Count of Monte Cristo.

This review was first published on Cheryl’s personal blog in March 2009. It is reprinted here to accompany the review of A Fire Born of Exile as both books are inspired by The Count of Monte Cristo.

Academic books don’t come much more obscure than ones examining mediaeval literature. However, I’m assuming that you folks have at least a passing interest in Arthuriana, and in the origins of literature, so hopefully you will find the following of interest.

Academic books don’t come much more obscure than ones examining mediaeval literature. However, I’m assuming that you folks have at least a passing interest in Arthuriana, and in the origins of literature, so hopefully you will find the following of interest.

And so, finally, I reach the end of The Dark is Rising sequence.

And so, finally, I reach the end of The Dark is Rising sequence.

I should confess from the start that I am not qualified to review an art book, let alone a book of the sort of fine art that Judith Clute produces. If you want the view of an expert in art, and the philosophy of art, read the essay by Pamela Zoline which appears at the end of this book. Hopefully it will appear, at some point,

I should confess from the start that I am not qualified to review an art book, let alone a book of the sort of fine art that Judith Clute produces. If you want the view of an expert in art, and the philosophy of art, read the essay by Pamela Zoline which appears at the end of this book. Hopefully it will appear, at some point,  Every so often, a TV series does something that is so off the wall that it is hard to discuss it without spoilers. Even if that wasn’t the case, it would be hard to discuss Season #2 of Loki without referencing the events at the end of Season #1. So please assume that this review will be somewhat spoilerific.

Every so often, a TV series does something that is so off the wall that it is hard to discuss it without spoilers. Even if that wasn’t the case, it would be hard to discuss Season #2 of Loki without referencing the events at the end of Season #1. So please assume that this review will be somewhat spoilerific. Fresh from their triumphant appearance in Strange New Worlds, our favorite ensigns are back in action, and the first thing that happens to them is that they all get promoted.

Fresh from their triumphant appearance in Strange New Worlds, our favorite ensigns are back in action, and the first thing that happens to them is that they all get promoted.