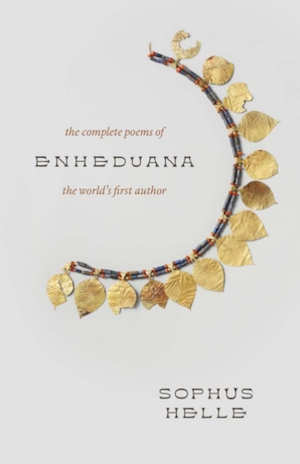

When I reviewed Sophus Helle’s new translation of Gilgamesh I made the point that Helle brings a highly unusual mix of talents to the task. He’s familiar with the literary world, and learned wordsmithing from his father who is one of Denmark’s foremost poets. But he is also an Assyriologist who can read Sumerian and Akkadian in their native cuneiform, and who has an excellent grasp of the cultures from which works such as Gilgamesh originated. This makes him the ideal person to also produce a translation of the first works of literature in human history to have been credited to an individual author. Hence, to give the book its full title: The Complete Poems of Enheduana, the world’s first author.

When I reviewed Sophus Helle’s new translation of Gilgamesh I made the point that Helle brings a highly unusual mix of talents to the task. He’s familiar with the literary world, and learned wordsmithing from his father who is one of Denmark’s foremost poets. But he is also an Assyriologist who can read Sumerian and Akkadian in their native cuneiform, and who has an excellent grasp of the cultures from which works such as Gilgamesh originated. This makes him the ideal person to also produce a translation of the first works of literature in human history to have been credited to an individual author. Hence, to give the book its full title: The Complete Poems of Enheduana, the world’s first author.

Enheduana was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad (the real one, not the far-right troll who uses that name on social media), a man who also staked his claim in history by becoming the world’s first emperor. It was Sargon who united the fiercely independent city-states of Sumer under his control, and who began the linguistic shift to the use of Akkadian rather than Sumerian as the principal language of the region.

Religion was a key instrument of social control at the time, so Sargon gave his daughter the key post of the High Priestess of the city of Ur. While the Sumerians broadly worshipped the same pantheon of gods, each city had a chief god to whom the main temple was dedicated. As High Priestess of Ur, Enheduana’s first duty was to Nanna, the god of the Moon. But she also seems to have had a particular fondness for Inana, the wild and unpredictable goddess of love and war (better known by her Akkadian name of Ishtar).

One of Enehduana’s surviving works is a lengthy hymn of praise to Inana. This is the work in which she describes the various powers of the goddess, including the ability to turn men into women, and women into men. Enheduana’s works make it clear that gender ambiguity was a key facet of Inana’s cult.

But the work for which Enheduana is most famous, because we have a complete copy of the text, is the one we now call “The Exaltation of Inana”. We have that copy because, 500 years after her death, Enheduana’s works were a key element of the curriculum in the schools of the Old Babylonian Empire. An archaeological excavation in Babylon chanced upon a building that must have housed a scribal school, because multiple, inexpertly written copies of the Exaltation were found there.

Because she was governing a Sumerian city, and was serving as High Priestess of a Sumerian god, Enheduana wrote her poems in Sumerian. That in itself is remarkable. The world’s first known author wrote her best-known works in her second language. But, in much the same way as Latin became the language of the church in mediaeval Europe, Sumerian was preserved as the language of religion for the Babylonians. And they trained their scribes on the work of the best known writer from (their) antiquity, who was a woman.

One of the benefits of having Helle write this book is that he is able to explain just how good a poet Enheduana was, because he is familiar with the language in which she was writing.

The Exaltation is not just a hymn of praise for a goddess. It is also autobiographical. Indeed, the fact that it needed to be may have been what prompted Enheduana to insert her name into the text. The Sumerians were not exactly happy about having been conquered by Sargon. In Ur, a rebellion led by a man called Lugal-Ane deposed Enheduana and forced her into exile. Having appealed to Nanna for help in vain, Enheduana turned to her favourite goddess instead. And that appeal is what the Exaltation is all about.

Our knowledge of the history of those times is inevitably sketchy, but we have a limestone disk showing an image of Enheduana performing her religious duties and inscribed with her name. It was found by Katharine Wooley, who oversaw much of the excavation of the city while her husband, Sir Leonard, was off giving lecture tours about how he discovered the birthplace of Abraham. We have also found the graves (identified by their personal seals) of her hairdresser, her steward, and one of her scribes. Her tomb, if it was in Ur, was probably looted and destroyed, because Ur was sacked by the Elamites after Sargon’s empire collapsed some decades after his death. Enheduana was most definitely a real person.

I’ve gone on a bit, but there are a few other things I would like to highlight. Firstly, at one point during the Exaltation, Enheduana says:

“Inana: I will let my tears stream free to soften your heart, as if they were beer.”

Ah, Sumerians, they did so love their beer. But, as Helle points out, there is also the implication that Inana finds human suffering intoxicating. Gods are weird people.

Next up, Helle notes that Enheduana describes the action of authorship as a form of weaving with words. He goes on to explain that, in the ancient world, originality was less valued than it is today (and copyright didn’t exist). What was valued was taking existing strands from well-loved works and weaving them into new and different forms. In other words, fanfic was a common form of literary expression (and The Aeneid is totally Homer fanfic).

What Helle doesn’t say is that weaving is, and pretty much always has been, women’s work. And if authorship is a form of weaving, that to me suggests that it too was probably practiced mostly by women.

Finally there is the question of Enheduana’s position in the annals of feminism. There is no doubt that, today, the fact that she is the world’s first known author is of great importance to women. However, Helle states that reading the Exaltation as a proto-feminist text would not make sense because, at the time of writing, “feminism had not yet been born.” I’d like to unpack that a little.

Comments like that always remind me, uncomfortably, of the people who claim that trans folk cannot have existed in the past because being trans had not been invented then. But that claim is heavily dependent on a definition of being trans that they, and generations of cisgender doctors, have created.

So when was feminism born? And who birthed it? Was it Mary Wolstonecroft? Margaret Cavendish? Christine de Pizan? Hypatia?

If we follow Marie Shear and define feminism as, “The radical notion that women are people,” then feminism will have existed as long as men have looked down on women as lesser beings. That, I suspect, takes us back well before Enheduana’s time. Helle himself notes that neither Inana nor Enheduana are typical of Sumerian womanhood:

“Women were expected to look after the house, cook, clean, wave, mash, manage the domestic expenses, and look after the children. They were supposed to be healthy, humble, caring, quiet, and attractive to look at.”

It is entirely true that Enheduana’s outrage at being deposed and exiled by Lugal-Ane is the outrage of the daughter of an emperor who has been rebelled against by one of the conquered. But we laud the suffragettes as feminist despite the fact that most of their leaders (Sylvia Pankhurst excepted) were not keen on allowing working class women the vote. They were not too keen on women of colour either, save for the fantastically wealthy princess Sophia Duleep Singh.

So my view is that Enheduana was doing the sort of feminism we might expect from an elite woman who had been deposed by a man of inferior status who very probably had told her that she, being a woman, had no right to rule over him. Also she suggests that he insulted her by claiming that she was not behaving as a woman should, but rather like that awful Inana of whom she was so fond.

In Enheduana’s time, poems did not have titles. They were known by the first line of the text. The Exaltation was therefore known as “Nin me ŝara.” That translates literally as “Queen of all the me,” where me is a Sumerian word meaning a skill or power. So metalworking, weaving and writing are me, but so are wisdom and justice. Weirdly the Sumerians seem to have believed that, at least in the divine realm, me took physical form and could be stolen by one god from another. Which is how Inana managed to steal a whole bunch of me from a male god called Enki, including the me for giving blow-jobs. I want to know what Enki was doing with it in the first place.

Helle translates the first line of the Exaltation as “Queen of all powers”, which is a good attempt to render me in a way that is understandable to modern readers. I would have rendered it as, “All-powerful Queen,” because Enheduana goes on to state that Inana is not just one god among many, she is the most powerful god of all. And claiming that the supreme god is female is, I submit, a profoundly feminist statement.

If anyone thinks that I need support from a professional Assyriologist, I note that Julian Reade suggested that Sennacherib might be a feminist.

That quibble aside, Enheduana is a wonderful book containing beautifully executed translations of Enheduana’s works, and insightful essays about them and their place in human and literary history.

Title:

Title: Enheduana

By: Sophus HellePublisher: Yale University Press

Purchase links:Amazon UKAmazon USBookshop.org UKSee

here for information about buying books though

Salon Futura

I’m a little surprised to see a new Alex Easton story. The first one seemed complete in itself. But novella series have been very successful so I’m not too surprised that this is happening.

I’m a little surprised to see a new Alex Easton story. The first one seemed complete in itself. But novella series have been very successful so I’m not too surprised that this is happening.

One of the great things about the ‘Perspectives on Fantasy’ series of academic books being produced by the Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic at the University of Glasgow is that all the books get a paperback edition at a price that mere humans can afford. You do have to wait about a year after the publication of the hardcover, but you will get it. I’ve been eagerly awaiting Taylor Driggers’ book, and am pleased I can finally own a copy.

One of the great things about the ‘Perspectives on Fantasy’ series of academic books being produced by the Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic at the University of Glasgow is that all the books get a paperback edition at a price that mere humans can afford. You do have to wait about a year after the publication of the hardcover, but you will get it. I’ve been eagerly awaiting Taylor Driggers’ book, and am pleased I can finally own a copy.

Here’s one you may not have heard of. Xan van Rooyen is a South African non-binary person currently living in Finland. Xan and I have been on a number of panels together at Nordic conventions, and at this year’s Finncon we will be discussing Queer Fantasies. Waypoint Seven, however, is not exactly a fantasy, it is a space opera with magic.

Here’s one you may not have heard of. Xan van Rooyen is a South African non-binary person currently living in Finland. Xan and I have been on a number of panels together at Nordic conventions, and at this year’s Finncon we will be discussing Queer Fantasies. Waypoint Seven, however, is not exactly a fantasy, it is a space opera with magic.

When I first started writing book reviews, I could count the number of trans authors active in the speculative fiction field on the fingers of one hand. These days they are everywhere. So welcome, Elaine Gallagher, previously best known as a Scottish poet, but now the latest in the stable of novella writers for Tor.com.

When I first started writing book reviews, I could count the number of trans authors active in the speculative fiction field on the fingers of one hand. These days they are everywhere. So welcome, Elaine Gallagher, previously best known as a Scottish poet, but now the latest in the stable of novella writers for Tor.com.

It was that time of year again, so off I went to Oxford for the annual Tolkien Lecture on Fantasy Literature. This year was a bit special. That was partly because at long last a memorial to Professor Tolkien was to be unveiled in Pembroke College. That was as much a project as the lecture series itself: something that Gabriel Shenk, Will Badger and their colleagues had pressed the college for from their student days. Because really Pembroke should make more of its most famous Fellow.

It was that time of year again, so off I went to Oxford for the annual Tolkien Lecture on Fantasy Literature. This year was a bit special. That was partly because at long last a memorial to Professor Tolkien was to be unveiled in Pembroke College. That was as much a project as the lecture series itself: something that Gabriel Shenk, Will Badger and their colleagues had pressed the college for from their student days. Because really Pembroke should make more of its most famous Fellow.

Our story begins in 2011 with the British Library’s first ever exhibition of science fiction. John Clute, inevitably, was called in to advise on the project. But he ended up doing rather more than that, including lending some books from his own collection for display. Because the British Library (BL), an institution tasked with being a repository for the nation’s literature, does a rather shoddy job of preserving books.

Our story begins in 2011 with the British Library’s first ever exhibition of science fiction. John Clute, inevitably, was called in to advise on the project. But he ended up doing rather more than that, including lending some books from his own collection for display. Because the British Library (BL), an institution tasked with being a repository for the nation’s literature, does a rather shoddy job of preserving books.

I’ve not been a great fan of Doctor Who over the past decade or so. That’s partly because I seem to be allergic to almost everything that Steven Moffat writes. But also I just didn’t get it. I mostly wasn’t very invested in the characters or the stories. I’m pleased to say that, with the new season, that’s all changed.

I’ve not been a great fan of Doctor Who over the past decade or so. That’s partly because I seem to be allergic to almost everything that Steven Moffat writes. But also I just didn’t get it. I mostly wasn’t very invested in the characters or the stories. I’m pleased to say that, with the new season, that’s all changed.

I gave up on the first of Cixin Liu’s novels because it was very slow, and reminded me of the sort of science fiction that I read when I was a teenager. Consequently I can’t comment on the quality of Benioff & Weiss’ TV show as an adaptation of the books. As I understand it, they have diverged radically from the original. So I’m going to judge it in isolation.

I gave up on the first of Cixin Liu’s novels because it was very slow, and reminded me of the sort of science fiction that I read when I was a teenager. Consequently I can’t comment on the quality of Benioff & Weiss’ TV show as an adaptation of the books. As I understand it, they have diverged radically from the original. So I’m going to judge it in isolation.

Furiosa is a prequel to Mad Max: Fury Road. It tells the story of the titular character from her girlhood through to become the capable woman that we know from the earlier film. It is, in other words, cashing in on the success of Fury Road. But is it worth it? Well…

Furiosa is a prequel to Mad Max: Fury Road. It tells the story of the titular character from her girlhood through to become the capable woman that we know from the earlier film. It is, in other words, cashing in on the success of Fury Road. But is it worth it? Well…

This is the May 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the May 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Ninth Life

Ninth Life The Brides of High Hill

The Brides of High Hill Thornhedge

Thornhedge The Association of Welsh Writing in English Conference

The Association of Welsh Writing in English Conference The Word

The Word Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits

Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits X-Men ’97

X-Men ’97 Star Trek Discovery – The Final Season

Star Trek Discovery – The Final Season Editorial – May 2024

Editorial – May 2024 This issue’s cover is the last of the Iain J Clark covers that I’m running to help promote the Glasgow Worldcon (and, of course, Iain’s work). This one is called Green(ock) Woman. I have no idwa what Scottish thistles smell like, having never got close enough to one to find out, but I love the concept.

This issue’s cover is the last of the Iain J Clark covers that I’m running to help promote the Glasgow Worldcon (and, of course, Iain’s work). This one is called Green(ock) Woman. I have no idwa what Scottish thistles smell like, having never got close enough to one to find out, but I love the concept.

If you, like me, have been avidly following this series from Stark Holborn, you will know that the first two books were called Ten Low and Hel’s Eight. You too many have been expecting the new book to have a Six in the title, and be somewhat bemused by the reversal of the counting sequence. However, there is sense to this (or at least what passes for sense on Factus, the Outlaw Moon).

If you, like me, have been avidly following this series from Stark Holborn, you will know that the first two books were called Ten Low and Hel’s Eight. You too many have been expecting the new book to have a Six in the title, and be somewhat bemused by the reversal of the counting sequence. However, there is sense to this (or at least what passes for sense on Factus, the Outlaw Moon).

You know the drill by now. Cleric Chih and their neixin, Almost Brilliant, are somewhere out in the world. They get into an adventure. Stories are told, and a mystery is solved. Except, of course, if Nghi Vo did the same thing with every story in the Singing Hills cycle, it would get quite dull. So she doesn’t. While every story has those core elements, each one proceeds very differently. Sometimes we are even deprived of the company of Almost Brilliant, as is the case for most of The Brides of High Hill, though I hope Vo won’t do that too often because the neixin is very much the star of the show.

You know the drill by now. Cleric Chih and their neixin, Almost Brilliant, are somewhere out in the world. They get into an adventure. Stories are told, and a mystery is solved. Except, of course, if Nghi Vo did the same thing with every story in the Singing Hills cycle, it would get quite dull. So she doesn’t. While every story has those core elements, each one proceeds very differently. Sometimes we are even deprived of the company of Almost Brilliant, as is the case for most of The Brides of High Hill, though I hope Vo won’t do that too often because the neixin is very much the star of the show.

Once upon a time there was a princess in a tower.

Once upon a time there was a princess in a tower.

One of the interesting things about conquests and colonization is how language shifts as a result. England was conquered by the Normans in 1066. The Norman aristocracy continued to speak French for a long time thereafter, but the English people never adopted that language and eventually the nobility started speaking English. It took the Normans a lot longer to extend their conquest into Wales, and it wasn’t really until the time of Henry VIII that Wales became fully subsumed into the British state. People in Wales continued to speak Welsh right up until the 19th Century, when the Victorians decided that the Welsh should be forced to speak English, on pain of strict punishment. Since Devolution, the Welsh language has seen something of a revival, at least in official spheres, but the rise of English as a world language has made it hard to explain to young Welsh people why they should have to learn their native tongue.

One of the interesting things about conquests and colonization is how language shifts as a result. England was conquered by the Normans in 1066. The Norman aristocracy continued to speak French for a long time thereafter, but the English people never adopted that language and eventually the nobility started speaking English. It took the Normans a lot longer to extend their conquest into Wales, and it wasn’t really until the time of Henry VIII that Wales became fully subsumed into the British state. People in Wales continued to speak Welsh right up until the 19th Century, when the Victorians decided that the Welsh should be forced to speak English, on pain of strict punishment. Since Devolution, the Welsh language has seen something of a revival, at least in official spheres, but the rise of English as a world language has made it hard to explain to young Welsh people why they should have to learn their native tongue. One of the reasons I’m interested in the subject of Welsh Writing in English is to enable me to track down Welsh science fiction and fantasy. There have been a few science fiction novels written in Welsh. Not all of them have been translated into English. There are also Welsh people who are famous in the SF&F community: Al Reynolds, Jo Walton and Gareth Powell, for example. There are Welsh immigrants you will have heard of too, including Jasper Fforde, Stephanie Burgis and Tim Lebbon. Mostly these folks are unknown on the Welsh literary scene. But there are also people writing SF&F in Wales, and being published in Wales, who seem completely unknown in the wider SF&F world.

One of the reasons I’m interested in the subject of Welsh Writing in English is to enable me to track down Welsh science fiction and fantasy. There have been a few science fiction novels written in Welsh. Not all of them have been translated into English. There are also Welsh people who are famous in the SF&F community: Al Reynolds, Jo Walton and Gareth Powell, for example. There are Welsh immigrants you will have heard of too, including Jasper Fforde, Stephanie Burgis and Tim Lebbon. Mostly these folks are unknown on the Welsh literary scene. But there are also people writing SF&F in Wales, and being published in Wales, who seem completely unknown in the wider SF&F world.

The history of witchcraft is a popular subject these days. However, most historians tend to focus on the social conditions that made witch hunting a popular and profitable occupation in early modern times. When asked to think about the accused, historians tend to assume that these were marginalized people who were easy to make into scapegoats, and whose confessions were largely the result of suggestion by their captors/torturers.

The history of witchcraft is a popular subject these days. However, most historians tend to focus on the social conditions that made witch hunting a popular and profitable occupation in early modern times. When asked to think about the accused, historians tend to assume that these were marginalized people who were easy to make into scapegoats, and whose confessions were largely the result of suggestion by their captors/torturers.

Data Point 1: I grew up on the X-Men. Thanks to Power Comics, I had access to X-Men stories from issue #1 (in Fantastic). I could also follow The Avengers in Terrific. Both of these became firm favourites because they had reasonable female characters (unlike British comics which were very gender-specific). Janet van Dyne was my role model—the sort of capable, independent and fashionable woman I hoped to grow up to be. But Jean Grey was my big sister—the closest thing I had to a character to identify with.

Data Point 1: I grew up on the X-Men. Thanks to Power Comics, I had access to X-Men stories from issue #1 (in Fantastic). I could also follow The Avengers in Terrific. Both of these became firm favourites because they had reasonable female characters (unlike British comics which were very gender-specific). Janet van Dyne was my role model—the sort of capable, independent and fashionable woman I hoped to grow up to be. But Jean Grey was my big sister—the closest thing I had to a character to identify with. Having sent the Discovery and her crew into the far future, Paramount seem to have decided to use the series to explore some classic science fiction themes. The finale of Season 4 owed a lot to the movie, Arrival, and of course the brilliant Ted Chaing story on which it is based. Season 5 mines another classic plot: alien technology so powerful that only our heroes should be allowed to have it.

Having sent the Discovery and her crew into the far future, Paramount seem to have decided to use the series to explore some classic science fiction themes. The finale of Season 4 owed a lot to the movie, Arrival, and of course the brilliant Ted Chaing story on which it is based. Season 5 mines another classic plot: alien technology so powerful that only our heroes should be allowed to have it.

This is the April 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the April 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Book of Love

The Book of Love Song of the Huntress

Song of the Huntress The Butcher of the Forest

The Butcher of the Forest Bird, Blood, Snow

Bird, Blood, Snow LuxCon 2024

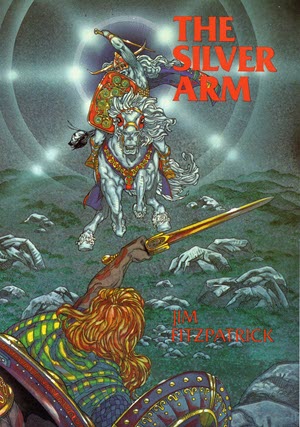

LuxCon 2024 The Silver Arm

The Silver Arm Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Monty Python and the Holy Grail This issue’s cover is the art that Ben Baldwin did for the new Lyda Morehouse novel, Welcome to Boy.net. As usual, there is an unadulterated version of the art below.

This issue’s cover is the art that Ben Baldwin did for the new Lyda Morehouse novel, Welcome to Boy.net. As usual, there is an unadulterated version of the art below.

For a couple of decades now, Kelly Link has been one of the stars of the fantasy short fiction scene. She’s won a Hugo, three Nebulas and three Word Fantasy Awards amongst a fine collection of trophies. And in all that time, people have been asking her, “Kelly, when are you going to write a novel?”

For a couple of decades now, Kelly Link has been one of the stars of the fantasy short fiction scene. She’s won a Hugo, three Nebulas and three Word Fantasy Awards amongst a fine collection of trophies. And in all that time, people have been asking her, “Kelly, when are you going to write a novel?”

I’ve been looking forward to this book for some time. I know Lucy Holland quite well and gave her a bit of historical help on her previous book, Sistersong, so I was aware of the struggles she was having with the new book. I’m very glad that all came to a successful conclusion.

I’ve been looking forward to this book for some time. I know Lucy Holland quite well and gave her a bit of historical help on her previous book, Sistersong, so I was aware of the struggles she was having with the new book. I’m very glad that all came to a successful conclusion.

Premee Mohamed is hugely popular with many of my friends. A lot of what she writes sounds a bit too much like horror for my tastes, but The Butcher of the Forest is a novella and it sounded more like dark fantasy, so I decided to give it a try. I’m glad I did.

Premee Mohamed is hugely popular with many of my friends. A lot of what she writes sounds a bit too much like horror for my tastes, but The Butcher of the Forest is a novella and it sounded more like dark fantasy, so I decided to give it a try. I’m glad I did.

As I’m writing a paper about Nicola Griffith’s Spear for an academic conference, I figured I should look for other modern versions of the Peredur story. As it happens, Seren’s series of Mabinogion re-tellings includes a version of Peredur. It is by Cynan Jones, who is a successful Welsh literary writer (published in Granta and the like). He’s not, as far as I can see, known for fantasy.

As I’m writing a paper about Nicola Griffith’s Spear for an academic conference, I figured I should look for other modern versions of the Peredur story. As it happens, Seren’s series of Mabinogion re-tellings includes a version of Peredur. It is by Cynan Jones, who is a successful Welsh literary writer (published in Granta and the like). He’s not, as far as I can see, known for fantasy.

Made it at last!

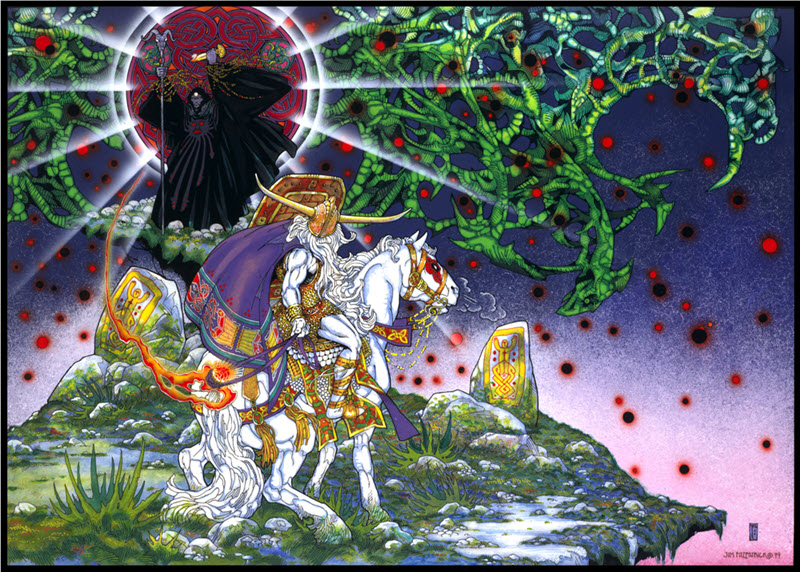

Made it at last! I have owned a copy of Jim Fitzpatrick’s The Book of Conquests for many years, but for some reason I never got a copy of the sequel. When I noticed a copy in my local bookstore, I figured it was about time to get one.

I have owned a copy of Jim Fitzpatrick’s The Book of Conquests for many years, but for some reason I never got a copy of the sequel. When I noticed a copy in my local bookstore, I figured it was about time to get one.

As noted elsewhere, I’m currently writing an academic paper about Spear, the Nicola Griffith novel based on the Mabinogion story of Peredur. Whenever one is discussing Peredur, it is necessary to also discuss the Holy Grail, even though that artefact never actually appears in the story. Later versions of the legend do include the Christian references, and these days they have taken over the narrative. And the most famous modern version of the story is undoubtedly the one featuring coconuts, anarchist peasants, and a great deal of running away.

As noted elsewhere, I’m currently writing an academic paper about Spear, the Nicola Griffith novel based on the Mabinogion story of Peredur. Whenever one is discussing Peredur, it is necessary to also discuss the Holy Grail, even though that artefact never actually appears in the story. Later versions of the legend do include the Christian references, and these days they have taken over the narrative. And the most famous modern version of the story is undoubtedly the one featuring coconuts, anarchist peasants, and a great deal of running away.

This is the March 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the March 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Library of Broken Worlds

The Library of Broken Worlds HIM

HIM ElfQuest, The TV Series

ElfQuest, The TV Series Mythical Monster Stories

Mythical Monster Stories Enheduana

Enheduana Dune 2

Dune 2 This Year’s Hugo Finalists

This Year’s Hugo Finalists Museum Bums

Museum Bums Spirited Away

Spirited Away This issue’s cover is Nøkken on a Bridge by Peter Dobbin, taken from his book, Mythical Monster Stories. The Nøkken is a water spirit from Scandinavian folklore, apparently fond luring young women to their deaths. A full version of the art as it appears in the book is included below.

This issue’s cover is Nøkken on a Bridge by Peter Dobbin, taken from his book, Mythical Monster Stories. The Nøkken is a water spirit from Scandinavian folklore, apparently fond luring young women to their deaths. A full version of the art as it appears in the book is included below.

I am annoyed with myself. I know how good Alaya Dawn Johnson is. I’ve really enjoyed some of her previous work. So I bought her latest book, and then put it aside because it is marketed as YA and I had lots of high-profile adult books to read. Consequently, until very recently, I did not get to what, in my humble opinion, is the best science fiction novel of 2023.

I am annoyed with myself. I know how good Alaya Dawn Johnson is. I’ve really enjoyed some of her previous work. So I bought her latest book, and then put it aside because it is marketed as YA and I had lots of high-profile adult books to read. Consequently, until very recently, I did not get to what, in my humble opinion, is the best science fiction novel of 2023.

The right wing part of social media has been in meltdown once again this month, this time over the fact that the disgusting trannies have failed to move the Trans Day of Visibility to a different day because Easter Sunday happens to have moved onto March 31st. How dare they? Easter has been cancelled!!! Oh dear.

The right wing part of social media has been in meltdown once again this month, this time over the fact that the disgusting trannies have failed to move the Trans Day of Visibility to a different day because Easter Sunday happens to have moved onto March 31st. How dare they? Easter has been cancelled!!! Oh dear.

Well, it’s taken 42 years, but it looks like ElfQuest fans, young and old, who have grown up with Richard and Wendy Pini’s creation since 1978, may have finally reached sorrow’s end.

Well, it’s taken 42 years, but it looks like ElfQuest fans, young and old, who have grown up with Richard and Wendy Pini’s creation since 1978, may have finally reached sorrow’s end. It is quite rare that I get sent books of any type these days. It is even more rare for me to get sent a graphic novel. So I was very surprised when Peter Dobbin asked me if I would like a review copy of his book, Mythical Monster Stories.

It is quite rare that I get sent books of any type these days. It is even more rare for me to get sent a graphic novel. So I was very surprised when Peter Dobbin asked me if I would like a review copy of his book, Mythical Monster Stories.

When I reviewed Sophus Helle’s new translation of Gilgamesh I made the point that Helle brings a highly unusual mix of talents to the task. He’s familiar with the literary world, and learned wordsmithing from his father who is one of Denmark’s foremost poets. But he is also an Assyriologist who can read Sumerian and Akkadian in their native cuneiform, and who has an excellent grasp of the cultures from which works such as Gilgamesh originated. This makes him the ideal person to also produce a translation of the first works of literature in human history to have been credited to an individual author. Hence, to give the book its full title: The Complete Poems of Enheduana, the world’s first author.

When I reviewed Sophus Helle’s new translation of Gilgamesh I made the point that Helle brings a highly unusual mix of talents to the task. He’s familiar with the literary world, and learned wordsmithing from his father who is one of Denmark’s foremost poets. But he is also an Assyriologist who can read Sumerian and Akkadian in their native cuneiform, and who has an excellent grasp of the cultures from which works such as Gilgamesh originated. This makes him the ideal person to also produce a translation of the first works of literature in human history to have been credited to an individual author. Hence, to give the book its full title: The Complete Poems of Enheduana, the world’s first author.

When the first part of Dune came out I was still very much avoiding movie theatres. This time I was able to see the film in the beautiful little cinema at Brynamman, which is very much how it was supposed to be viewed. I even got an ice cream in the intermission between the tailers and the main feature.

When the first part of Dune came out I was still very much avoiding movie theatres. This time I was able to see the film in the beautiful little cinema at Brynamman, which is very much how it was supposed to be viewed. I even got an ice cream in the intermission between the tailers and the main feature. Well, here we go again. And with many people in fandom having declared that the Hugos are over and deserve to die in a fire, what are we to make of

Well, here we go again. And with many people in fandom having declared that the Hugos are over and deserve to die in a fire, what are we to make of