I owe this one to Finncon, or more precisely to the traditional academic conference that takes places on the Friday before Finncon. Irma messaged me to tell me that one of the papers was about Oryx and Crake, and this strange academic book, neither of which I was familiar with. Could I help? Well, I had some memory of reading Oryx and Crake, and being deeply unimpressed. But as for this Ghost Stories for Darwin thing? A book on evolutionary biology written by a woman with a very Indian name. WTF? As I believe people say these days.

I owe this one to Finncon, or more precisely to the traditional academic conference that takes places on the Friday before Finncon. Irma messaged me to tell me that one of the papers was about Oryx and Crake, and this strange academic book, neither of which I was familiar with. Could I help? Well, I had some memory of reading Oryx and Crake, and being deeply unimpressed. But as for this Ghost Stories for Darwin thing? A book on evolutionary biology written by a woman with a very Indian name. WTF? As I believe people say these days.

My expectations were not improved when I started to read the book on the train to Jyväskylä. I explained to Ursula Vernon and her husband, Kevin, why I would have my nose in a book during the trip. They looked at me as if I had just confessed some sort of masochist fetish. What good could possibly come of this bizarre exercise in self-immolation?

I have to admit that I wasn’t expecting much myself. I have always viewed evolutionary biologists as being insecure white men who are racist, misogynist, queerphobic and ableist, and who invent pseudoscientific theories to justify their bigotries; said theories being provable as correct solely by the existence of patriarchy.

Thankfully I soon changed my mind. Banu Subramaniam grew up in India and traveled to the USA to pursue a PhD in evolutionary biology. She was, by her own admission, naive and starry-eyed. She saw the USA as being a land free of the classism she was familiar with in India, she saw science as being a discipline free of sexism, and she had no idea about the level of racism in US culture. That she survived the experience is a testament to her strength of will, and also to the support she gained from the Women’s Studies department in her university.

Subramaniam’s subject for her PhD was the Morning Glory, a plant closely related to the notorious British Convolvulus, hated by gardeners throughout the land. The convolvulus does have very pretty white flowers (there will probably be lots in my back yard when I get home), but the morning glory has a wide variety of flower colourations, and it is these that Subramaniam was planning to study.

Doing so, and in the process experiencing life as a woman of colour in the USA, led to a political awakening that has established Subramaniam as one of the foremost experts on gender in the sciences. And if that immediately brings to mind the phrase, “women in science”, well you are exactly the sort of ill-informed person that Ghost Stories for Darwin is intended for.

I should note at the start that the book does not entirely succeed. Subramaniam is not a professional science communicator, and there are times, particularly when she is talking about her own academic specialisms, that she veers into complex jargon. Thankfully I have a science degree and was able to make sense of most of it, but other readers may find it very hard going.

Being an academic book, Ghost Stories for Darwin has a subtitle. It is, The Science of Variation and The Politics of Diversity. This is a good place to start looking at the argument. One of the great debates within evolutionary biology is the role of variation in evolution. Some people in the field believe that diversity has an evolutionary advantage for the species, as that provides a wide range of mutations to help it evolve into something better. Others believe that all variation is bad, and that only the fittest variation should be allowed to pass its genes on to new generations. This latter view leads inevitably to eugenics.

But, and here is our first important feminist lesson of the day, all binaries are false. Neither of the explanations above helps us understand why variation in the colour of morning glory flowers persists through hundreds of generations, and can exhibit stable shares of the population to which the species will return if the balance is perturbed. Variation in flower colour appears to be baked in to the morning glory as a species.

The answer to this conundrum is that evolution is not just driven by genetics. It is also influenced by a range of environmental factors including, but not limited to, climate, pollinator preference, soil conditions, human cultivation and so on. Subramaniam quickly discovered that the scientific ideas of doing a simple, one-variable experiment on a field of morning glory flowers tells you nothing.

Exploring the underlying assumptions of her field, and seeking support as a doubly marginalized person within US academia, led Subramaniam both to discover the horrendous eugenicist underpinning of her discipline, and the fundamentally masculinist nature of science as it is practiced.

One interesting aspect of Subramaniam’s section on eugenics is the fact that many of the pioneers of the field saw themselves as striving for a better world, and even as being good Socialists. The idea that the socially inferior should, for their own good, not be allowed to survive, is deeply seductive. While most of the extreme horrors perpetrated in the name of this belief have been minority ethnic groups, the differently abled and queer communities can recognise the syndrome. There have been many times when I have been told that my life would have been easier had I not been born.

Subramaniam moves on from eugenics to matters of race, and the complicated discipline known as Invasion Biology. We are all, I am sure, familiar with stories about how our native ecosystems are being “invaded” by dangerous foreign plants that are “taking over” and “crowding out” native species. Would it surprise you that there is a direct correlation between the frequency of such stories in the newspapers and the level of popular concern about human immigration? And the two types of story use exactly the same types of language.

Of course migration of plant species around the world has a long and in many cases glorious history. Where would our cuisines be without the potato, the tomato, and the chili pepper, all of which were unknown outside the Americas before Columbus accidentally ran into them on his way to India. The famous Georgia Peach is an immigrant from China. The same is true for animal species, though sometimes a little creative marketing is required. The Patagonia Toothfish was unheard of in restaurants before it cleverly changed its name to the Chilean Sea Bass.

The final section of the book is about gender, and it focuses on how the practice of science has been socially constructed in a very masculine fashion. A woman wishing to practice science has to buy into that construction and present herself as “one of the boys” in order to be taken seriously as a scientist. She must not wear make-up, she must not show emotion, and so on. Or at least, she should do so inside the lab. Outside the lab, in social spaces, she must present as conventionally feminine. After all, she will soon want to give up her career and become a wife and mother instead.

Feminist lesson two of the day is that all too often talk of gender focuses solely on the “woman problem”. It talks about how women must change themselves in order to fit into the masculine world, or about the accommodations that must be made for women because they do things like have families. (Men never have families, they have wives to do that for them.) Subramaniam says:

[…] the consistent emphasis on family and women reinforces essentialist ideas about women. What has remained unchallenged is the normative model of the male as the ideal scientist, which insists on productivity that can only be achieved by very long hours, a singular dedication to work, and an exclusive focus on one’s profession.

It occurs to me that many of the lessons Subramaniam presents about life in academia, particularly about the sink-or-swim culture of graduate education, are equally applicable outside of the sciences. Indeed, the failure of senior staff to properly train their subordinates in anything other than the technical aspects of the job at hand (and not in how to do things like be a good manager) is endemic in the world of work at large.

Ghost Stories for Darwin was published in 2014, and there are probably areas where its analysis of academic culture in the USA are out of date. In particular, while Subramaniam did see the commercialization of universities coming, she did not know how close it would come to destroying the institutions it was supposed to rescue.

I noted also that there is very little discussion of sexuality as a marginalized identity. Subramaniam does note that it is an issue, but when she actually talks about it she tends to do so by contrasting the profoundly asexual nature of laboratory life with the expectation of normative heterosexuality outside of the lab. She does make brief note of the famous trans masculine neurobiologist, Ben Barres, to illustrate just how foolish misogynist ideas of what makes a good scientist are, but her discussion of gender is primarily limited to performance rather than identity.

These, however, are minor quibbles. Ghost Stories for Darwin is a fascinating and well-argued book that gave me lots of useful pointers as to how to think about gender and its effects on the world.

Which leaves us with one question: where do the ghosts come in? It turns out that Subramaniam has borrowed the metaphor from Bollywood cinema. In a Bollywood movie, a ghost is always someone who has been unjustly forgotten and ignored after their death, and perhaps in life. They desperately want to be listened to, understood, acknowledged, and recognized so that they can stop haunting the living and rest in peace. The history of feminism, in all areas of life, is a story of Bollywood ghosts.

Title:

Title: Ghost Stories for Darwin

By: Banu SubramaniamPublisher: University of Illinois Press

Purchase links:Amazon UKAmazon USBookshop.org UKSee

here for information about buying books though

Salon Futura

Helen L Brady is a new addition to the Wizard’s Tower stable. Here Cheryl talks to Helen about her career in screenwriting and why she has moved into novels instead. They also touch on Helen’s work in costuming for theatre, and her past in historical re-enactment. Helen also talks about her first experiences of science fiction conventions at Worldcon and Bristolcon.

Helen L Brady is a new addition to the Wizard’s Tower stable. Here Cheryl talks to Helen about her career in screenwriting and why she has moved into novels instead. They also touch on Helen’s work in costuming for theatre, and her past in historical re-enactment. Helen also talks about her first experiences of science fiction conventions at Worldcon and Bristolcon.

And breathe! The convention circuit is over for the year.

And breathe! The convention circuit is over for the year.

If you look carefully at the poster for the TV series that accompanies this review, you will see that it says at the top, “From the twisted minds that brought you WandaVision”. Never a truer word…

If you look carefully at the poster for the TV series that accompanies this review, you will see that it says at the top, “From the twisted minds that brought you WandaVision”. Never a truer word…

Team-up movies are the bro version of enemies-to-lovers lesbian romances. You put two lads with very different personalities together. They fight a lot. And they end up sharing a beer and slapping each other on the back in a just good friends really sort of way.

Team-up movies are the bro version of enemies-to-lovers lesbian romances. You put two lads with very different personalities together. They fight a lot. And they end up sharing a beer and slapping each other on the back in a just good friends really sort of way.

This is the October 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the October 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Moonlight Market

The Moonlight Market The Knife and the Serpent

The Knife and the Serpent On the Economics of Small Presses

On the Economics of Small Presses BristolCon 2024

BristolCon 2024 The Sheep Look Up

The Sheep Look Up The Wood at Midwinter

The Wood at Midwinter Rings of Power – Season 2

Rings of Power – Season 2 FantasyCon 2024

FantasyCon 2024 Editorial – October 2024

Editorial – October 2024 This month’s cover is the art that Ben Baldwin did for Juliet McKenna’s latest novel, The Green Man’s War. Each time we do a new Green Man book, Ben seems to out-do himself in cover quality. We are so very lucky to have him.

This month’s cover is the art that Ben Baldwin did for Juliet McKenna’s latest novel, The Green Man’s War. Each time we do a new Green Man book, Ben seems to out-do himself in cover quality. We are so very lucky to have him.

Joanne Harris is, of course, a hugely well-known and respected writer of mainstream fiction. She’s a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, which is not the sort of honour that is doled out to hoi polloi of genre like us. And yet, she turns up at conventions. She was at Worldcon in Glasgow, and she’s a Guest of Honour at this year’s BristolCon. I first met her at FantasyCon the previous time it was in Chester.

Joanne Harris is, of course, a hugely well-known and respected writer of mainstream fiction. She’s a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, which is not the sort of honour that is doled out to hoi polloi of genre like us. And yet, she turns up at conventions. She was at Worldcon in Glasgow, and she’s a Guest of Honour at this year’s BristolCon. I first met her at FantasyCon the previous time it was in Chester.

If I need something that will be a quick and entertaining read, not too challenging or depressing, I know I can always rely on Tim Pratt. Their books are inventive, amusing, and contain just enough mild peril to keep you reading. The books also tend to include a few queer characters, Pratt being genderfluid, which is nice.

If I need something that will be a quick and entertaining read, not too challenging or depressing, I know I can always rely on Tim Pratt. Their books are inventive, amusing, and contain just enough mild peril to keep you reading. The books also tend to include a few queer characters, Pratt being genderfluid, which is nice.

At World Fantasy this year, Scott Andrews of Beneath Ceaseless Skies gave

At World Fantasy this year, Scott Andrews of Beneath Ceaseless Skies gave  The Green Man’s War is currently available for pre-order (

The Green Man’s War is currently available for pre-order ( This year saw the 15th iteration of BristolCon, and the first that was a whole weekend long rather than just Saturday. Con Chair MEG was upfront about this being an experiment. Lots of people had asked for it, but the only way to know if it would work was to try it.

This year saw the 15th iteration of BristolCon, and the first that was a whole weekend long rather than just Saturday. Con Chair MEG was upfront about this being an experiment. Lots of people had asked for it, but the only way to know if it would work was to try it. This review was first published

This review was first published

When Susanna Clarke produces a novel it makes a huge amount of money for Bloomsbury. Naturally they would love her to do so regularly. Probably more so now as their other best-selling author is doing everything she can to trash her own reputation. But Clarke seems to produce novels only once a decade. Therefore, Bloomsbury will push out absolutely anything as the new Susanna Clarke book, as long as it is something she has written. If she sent them her shopping list, they would probably publish that.

When Susanna Clarke produces a novel it makes a huge amount of money for Bloomsbury. Naturally they would love her to do so regularly. Probably more so now as their other best-selling author is doing everything she can to trash her own reputation. But Clarke seems to produce novels only once a decade. Therefore, Bloomsbury will push out absolutely anything as the new Susanna Clarke book, as long as it is something she has written. If she sent them her shopping list, they would probably publish that.

Amazon’s Tolkien vehicle continues to be Marmite for fans. I’ve seen some people who have been hate-watching it, and others who love it to pieces. There doesn’t seem to be much in between.

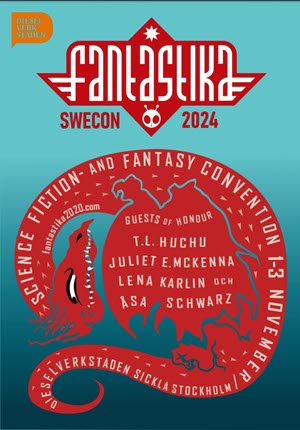

Amazon’s Tolkien vehicle continues to be Marmite for fans. I’ve seen some people who have been hate-watching it, and others who love it to pieces. There doesn’t seem to be much in between. I hadn’t been intending to go to FantasyCon this year because October was busy enough already. Or, at least, I didn’t think I had a membership and I wasn’t going to buy one. Then, about a month before the convention, I got sent some programme assignments. I hastily checked with the con, and lo, I did have a membership. I must have bought it last year and then forgotten about it. The programme assignments sounded interesting, and Chester is a great place to visit, so I decided to go.

I hadn’t been intending to go to FantasyCon this year because October was busy enough already. Or, at least, I didn’t think I had a membership and I wasn’t going to buy one. Then, about a month before the convention, I got sent some programme assignments. I hastily checked with the con, and lo, I did have a membership. I must have bought it last year and then forgotten about it. The programme assignments sounded interesting, and Chester is a great place to visit, so I decided to go.

This is the September 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the September 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Space Oddity

Space Oddity The Sunforge

The Sunforge Eyes of the Void

Eyes of the Void Star Trek Prodigy – Season #2

Star Trek Prodigy – Season #2 Speculative Insight

Speculative Insight The Acolyte

The Acolyte This is the cover art that Ben Baldwin produced for Resurrection Code, the fifth book in Lyda Morehouse’s AngeLINK series. The previous four covers had been done by Bruce Jensen. As he wasn’t available this time round, we asked Ben to produce something in the same style. The only other direction he got was that the central figure should be a mouse avatar, and that the background should be Egyptian-themed. He delivered magnificently.

This is the cover art that Ben Baldwin produced for Resurrection Code, the fifth book in Lyda Morehouse’s AngeLINK series. The previous four covers had been done by Bruce Jensen. As he wasn’t available this time round, we asked Ben to produce something in the same style. The only other direction he got was that the central figure should be a mouse avatar, and that the background should be Egyptian-themed. He delivered magnificently.

Get your feather boas and glitter ready, folks. It is time for another round of the Metagalactic Grand Prix! Or, in other words, Catherynne M Valente has written a sequel to Space Opera.

Get your feather boas and glitter ready, folks. It is time for another round of the Metagalactic Grand Prix! Or, in other words, Catherynne M Valente has written a sequel to Space Opera.

I’ve been looking forward to this book for some time. It was clear from the first book in the series, The Dawnhounds, that there was a lot to be learned about the world in which the book is set. In particular, while some of the characters are able to do magic, and attribute this to the favour of gods, it is obvious that the gods are actually people (and therefore not actually gods, if you were at the “Gods in Fantasy” panel at Worldcon).

I’ve been looking forward to this book for some time. It was clear from the first book in the series, The Dawnhounds, that there was a lot to be learned about the world in which the book is set. In particular, while some of the characters are able to do magic, and attribute this to the favour of gods, it is obvious that the gods are actually people (and therefore not actually gods, if you were at the “Gods in Fantasy” panel at Worldcon).

I very much enjoyed the first book in Adrian Tchaikovsky’s The Final Architecture series, and bought the other two books as soon as they came out. But they are enormous, which is a bit off-putting when you have a lot of books to read. Thankfully the Best Series Hugo gave me the impetus I needed to get back into the saddle.

I very much enjoyed the first book in Adrian Tchaikovsky’s The Final Architecture series, and bought the other two books as soon as they came out. But they are enormous, which is a bit off-putting when you have a lot of books to read. Thankfully the Best Series Hugo gave me the impetus I needed to get back into the saddle.

The new edition of Resurrection Code is due for release on October 3rd. Lyda and I are very excited about this, because at last the AngeLINK series has all five books back in print and looking line a set. So we did a podcast to talk about how the book came to be, and why we wanted it as it is.

The new edition of Resurrection Code is due for release on October 3rd. Lyda and I are very excited about this, because at last the AngeLINK series has all five books back in print and looking line a set. So we did a podcast to talk about how the book came to be, and why we wanted it as it is. The animation folks at Star Trek have another huge success on their hands. Whereas Lower Decks manages to love Trek whilst thoroughly taking the piss out of it, Prodigy has turned into a classic Trek series with a full-on space opera story arc and plenty of great Trek moments.

The animation folks at Star Trek have another huge success on their hands. Whereas Lower Decks manages to love Trek whilst thoroughly taking the piss out of it, Prodigy has turned into a classic Trek series with a full-on space opera story arc and plenty of great Trek moments. One of the things that irritates me about the world is that non-fiction is valued much less highly than fiction. I could see this when I was editing non-fiction for Clarkesworld. It was clear from the reader surveys that a lot of the readers didn’t bother with the content I was acquiring. They just read the fiction. And when I tried running Salon Futura as a paying venue for non-fiction, it quickly became obvious that most SF&F readers were not willing to pay for a non-fiction magazine. You can see the same thing in the wider book-publishing world too. Academics are generally expected to write for free, despite the fact that the books they write are sold for ridiculous amounts. And public historians are moving more and more into what is called “creative non-fiction”. Meanwhile garbage like Ancient Apocalypse gets made for Netflix while actual archaeologists can’t get a look-in.

One of the things that irritates me about the world is that non-fiction is valued much less highly than fiction. I could see this when I was editing non-fiction for Clarkesworld. It was clear from the reader surveys that a lot of the readers didn’t bother with the content I was acquiring. They just read the fiction. And when I tried running Salon Futura as a paying venue for non-fiction, it quickly became obvious that most SF&F readers were not willing to pay for a non-fiction magazine. You can see the same thing in the wider book-publishing world too. Academics are generally expected to write for free, despite the fact that the books they write are sold for ridiculous amounts. And public historians are moving more and more into what is called “creative non-fiction”. Meanwhile garbage like Ancient Apocalypse gets made for Netflix while actual archaeologists can’t get a look-in. I really wanted to like this series. It had Carrie-Ann Moss. It featured a trans actress (Abigail Thorn). There was significant writing and production involvement for Jen Richards, who is one of the most successful trans women in Hollywood. It would really have annoyed the dudebros had the show been a big success.

I really wanted to like this series. It had Carrie-Ann Moss. It featured a trans actress (Abigail Thorn). There was significant writing and production involvement for Jen Richards, who is one of the most successful trans women in Hollywood. It would really have annoyed the dudebros had the show been a big success.

This is the August 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the August 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Echo of Worlds

Echo of Worlds Beyond the Light Horizon

Beyond the Light Horizon A Marvellous Light

A Marvellous Light Rose/House

Rose/House Worldcon #82

Worldcon #82 Finncon 2024

Finncon 2024 Ghost Stories for Darwin

Ghost Stories for Darwin What Is Hopepunk?

What Is Hopepunk? For this issue’s cover we are back to Pixabay and a very nice far future archaelogists piece from Gordon Taylor. As usual, you can find out more about the artist by these convenient links:

For this issue’s cover we are back to Pixabay and a very nice far future archaelogists piece from Gordon Taylor. As usual, you can find out more about the artist by these convenient links:

Here is a book that I have been eagerly waiting for some time, and now find very difficult to review. Mike Carey’s Pandominium duology is not two separate novels, it is one long novel split in two for publication purposes, and with some shock reveals at the end of part 1 that make talking about part 2 in a spoiler-free way quite challenging.

Here is a book that I have been eagerly waiting for some time, and now find very difficult to review. Mike Carey’s Pandominium duology is not two separate novels, it is one long novel split in two for publication purposes, and with some shock reveals at the end of part 1 that make talking about part 2 in a spoiler-free way quite challenging.

When I reviewed Beyond the Reach of Earth, the second volume in Ken MacLeod’s Lightspeed Trilogy, I found myself asking why there will be a book three. Clearly there were unanswered questions at the end of that book, but exactly which ones MacLeod would pick up and run with was another matter entirely. As it turned out, Beyond the Light Horizon is something else entirely.

When I reviewed Beyond the Reach of Earth, the second volume in Ken MacLeod’s Lightspeed Trilogy, I found myself asking why there will be a book three. Clearly there were unanswered questions at the end of that book, but exactly which ones MacLeod would pick up and run with was another matter entirely. As it turned out, Beyond the Light Horizon is something else entirely.

I was familiar with all of the Best Series finalists for this year’s Hugos bar one: The Last Binding by Freya Marske. Therefore I decided to give the first book a try. A Marvelous Light could probably be described as being in the subgenre of English Magic fantasies. Like Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, it centers on the fact that some people in England (upper class people, obviously) have preserved magical skills over the ages and now (in this case in Edwardian times rather than Georgian) this is becoming a matter of political importance.

I was familiar with all of the Best Series finalists for this year’s Hugos bar one: The Last Binding by Freya Marske. Therefore I decided to give the first book a try. A Marvelous Light could probably be described as being in the subgenre of English Magic fantasies. Like Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, it centers on the fact that some people in England (upper class people, obviously) have preserved magical skills over the ages and now (in this case in Edwardian times rather than Georgian) this is becoming a matter of political importance.

There was some pretty stiff competition in the Novella category for the Hugos this year. I have already reviewed Thornhedge, Mammoths at the Gates, and The Mimicking of Known Successes, all of them favourably. But there was also an Arkady Martine story on the list, and I’ve loved everything of hers I have read. How would Rose/House stack up to the others?

There was some pretty stiff competition in the Novella category for the Hugos this year. I have already reviewed Thornhedge, Mammoths at the Gates, and The Mimicking of Known Successes, all of them favourably. But there was also an Arkady Martine story on the list, and I’ve loved everything of hers I have read. How would Rose/House stack up to the others?

While I have been to many Worldcons, this was the first one at which I have been a dealer. The experience is very different. It is also my first post-COVID Worldcon, which also changed things a lot.

While I have been to many Worldcons, this was the first one at which I have been a dealer. The experience is very different. It is also my first post-COVID Worldcon, which also changed things a lot. It is great to be back. One of the worst things about the pandemic was that I could not make my regular trips to Finland. I have been suffering sauna-deprivation.

It is great to be back. One of the worst things about the pandemic was that I could not make my regular trips to Finland. I have been suffering sauna-deprivation. I owe this one to Finncon, or more precisely to the traditional academic conference that takes places on the Friday before Finncon. Irma messaged me to tell me that one of the papers was about Oryx and Crake, and this strange academic book, neither of which I was familiar with. Could I help? Well, I had some memory of reading Oryx and Crake, and being deeply unimpressed. But as for this Ghost Stories for Darwin thing? A book on evolutionary biology written by a woman with a very Indian name. WTF? As I believe people say these days.

I owe this one to Finncon, or more precisely to the traditional academic conference that takes places on the Friday before Finncon. Irma messaged me to tell me that one of the papers was about Oryx and Crake, and this strange academic book, neither of which I was familiar with. Could I help? Well, I had some memory of reading Oryx and Crake, and being deeply unimpressed. But as for this Ghost Stories for Darwin thing? A book on evolutionary biology written by a woman with a very Indian name. WTF? As I believe people say these days.

For me, the most interesting panel at Finncon was the one on Hopepunk. It is not a genre that I have paid much attention to in the past. I had a vague idea that to qualify as Hopepunk a book had to be unchallenging, heartwarming and relentlessly positive, after the manner of a Travis Baldree novel. This panel disabused me of that notion, and also got me thinking that Wizard’s Tower might have published some Hopepunk.

For me, the most interesting panel at Finncon was the one on Hopepunk. It is not a genre that I have paid much attention to in the past. I had a vague idea that to qualify as Hopepunk a book had to be unchallenging, heartwarming and relentlessly positive, after the manner of a Travis Baldree novel. This panel disabused me of that notion, and also got me thinking that Wizard’s Tower might have published some Hopepunk.

This is the June 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the June 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. What Feasts at Night

What Feasts at Night Queering Faith in Fantasy Literature

Queering Faith in Fantasy Literature Waypoint Seven

Waypoint Seven Unexploded Remnants

Unexploded Remnants Tolkien Lecture 2024

Tolkien Lecture 2024 The Book Blinders

The Book Blinders Doctor Who 15-1

Doctor Who 15-1 3 Body Problem – Netflix

3 Body Problem – Netflix Furiosa

Furiosa This is the art that Ben Baldwin did for the lastest Chaz Brenchley Crater School book, Mary Ellen, Craterean! As always, an unadulterated version of the art can be found below.

This is the art that Ben Baldwin did for the lastest Chaz Brenchley Crater School book, Mary Ellen, Craterean! As always, an unadulterated version of the art can be found below.