I saw Cats in the theatre not long after it started. As I recall, Elaine Paige had moved on, but Brian Blessed and Bonnie Langford were still in it, as were most of the original cast. It was a fabulous experience. I know the soundtrack very well. So I was interested to see that there was going to be a movie, and not nearly as creeped out by the trailer as most people. Then the reviews started coming in, and it was clear that something had gone badly wrong. After all, this is a film of the longest-running musical in both London and New York. How could it tank so badly? As it happened, I had picked up the video of the stage show just before Christmas (HMV had it on sale), so I watched that, and then went to see the movie.

I saw Cats in the theatre not long after it started. As I recall, Elaine Paige had moved on, but Brian Blessed and Bonnie Langford were still in it, as were most of the original cast. It was a fabulous experience. I know the soundtrack very well. So I was interested to see that there was going to be a movie, and not nearly as creeped out by the trailer as most people. Then the reviews started coming in, and it was clear that something had gone badly wrong. After all, this is a film of the longest-running musical in both London and New York. How could it tank so badly? As it happened, I had picked up the video of the stage show just before Christmas (HMV had it on sale), so I watched that, and then went to see the movie.

I’d like to start with something that Cats has done well. The original show contained a sequence based on the poem, “Growltiger’s Last Stand.” It is horribly racist, and that was obvious at the time. That sequence has since been cut from the stage show, and is not in the video. There is another sequence based on the poem, “The Awefull Battle of the Pekes and the Pollicles” which has a few racist lines in. That was kept for the video, but neither of those sequences is in the movie. So you see, folks, it is entirely possible to take problematic material from the past and update it so that it is no longer offensive. All you have to do is care enough to do it.

Reading some of the comment on social media, I came to the conclusion that many of the complaints were coming from people who had never seen the stage show, and consequently didn’t know what to expect. In many ways these comments mirror the controversy that surrounded the show when it first launched. The extras on the video disc have clips of respectable BBC culture critics (Michael Parkinson, Joan Bakewell and Barry Norman) all expressing shock and disbelief that grown men and women would be cavorting around the stage pretending to be cats. I mean, what next? Would people be pretending to be elves? Or little green men from Mars?

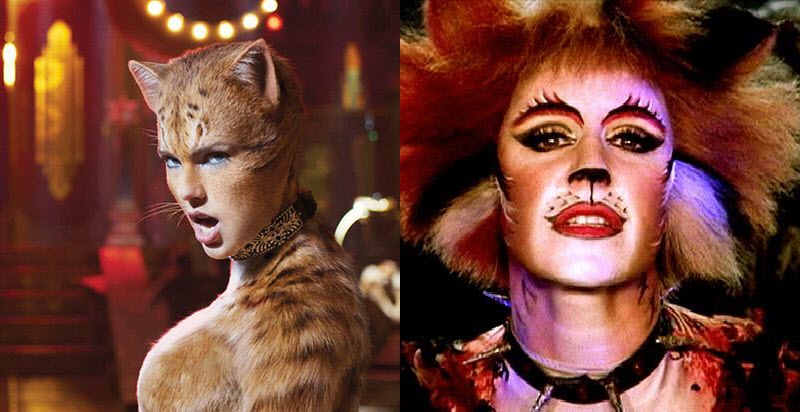

Cats was always going to be an exercise is suspension of disbelief. You had to want to see a show in which all of the characters are cats, and you had to believe in them. The stage show put a lot of effort into make-up and character behaviour to help with this.

The movie, I think relied too much on technical wizardry.

The body fur and the movement of the ears and tails is very good indeed, but I think that there are aspects that the cast either thought, or were told, that the CGI would take care of. The hands are a good example of that. In the stage show the cast work hard to hold their hands like cat paws. In the movie hands are human hands.

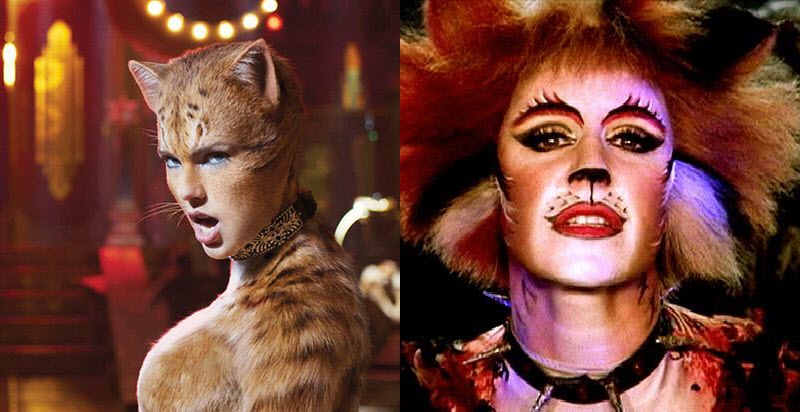

The mixture of human and feline isn’t necessarily bad. TS Eliot’s widow, Valerie, told Andrew Lloyd Webber that she’d turned down a request by Disney to make a cartoon of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats because she felt that they would make the characters look just like real cats. So the characters have to be a bit human. But there’s a very fine line between convincing and the uncanny valley. Faces are an obvious example. In the stage show the cast’s faces are heavily made up to look like cat faces. In the movie the characters have human faces on cat bodies. I have a feeling that someone in management said that the stars had to be recognisable.

The animals with human faces thing extended to the mice and cockroaches. In the stage show everyone other than a cat is played by a cat in costume. It is part of the show that they put on for Deuteronomy. The movie goes away from that and it doesn’t work well. Someone in the costume department had seen Ant Man & The Wasp and thought copying Hope Van Dyne’s outfit was a good idea.

But the thing that really creeped me out about the movie was the scale. The original stage show has a single set in a junk yard (this was apparently a deliberate pun – the cats live in a Waste Land). The bits of junk are sized appropriately for the cats, but as backdrops go it is fairly neutral. The movie has a whole range of different sets that are very much human settings. And because the characters spend much of their time walking like humans you get that “people in a giant’s castle” effect that takes away from the fact that you are supposed to be watching cats.

I can’t be certain about this, but I suspect that the movie’s VFX people didn’t put a lot of thought into the scaling. They just made the sets look bigger than the cats. But different sets were differently big and sometimes the same set was differently big in different shots. At least that’s how it seemed to me watching it.

And then there was the downright sloppy. There were times when the backgrounds looked very obviously painted.

Something else that has drawn comment is that come some of the cats wear fur coats. This has always been part of the stage show. I think it is intended to express parts of their personality. I’ve never really understood it, but it does seem to intrude more in the movie because of the quality of the cat-fur CGI. The more realistic-looking the cats are, the less you can give them ridiculous costumes.

Another issue may be to do with the cast being more distant. Cats was designed to be staged in the round, and the cast would run up and down the aisles during some of the more energetic numbers. If you were on the end of a row there was always the possibility of a cat coming to say hello. That made the audience part of the Jellice Ball gathering. You were one of them. That doesn’t work in the cinema because the cats are up there on the screen and you are down in the auditorium.

One of the things that shows a commenter hasn’t seen the stage show is the complaint that the cats in the movie are too sexy. Oh, you poor, innocent children. First up, they are cats, of course they are sexy. It is in their nature. And second, look at the characters. In the stage show Rum Tum Tugger is Cat Elvis. Jason Derulo has chosen to make him Cat James Brown instead, but the effect is the same and it is an entirely honourable substitution. The female cats all drool over him. On the extras for the video Gillian Frank, the choreographer, describes Victoria’s dance as, “a young female cat discovering her body after puberty.”

Then there’s McCavity’s song, which if you listen to it you will have to admit that it could easily be used in a strip club. Taylor Swift does a decent job of performing it, but if you take a look at the video you will get to see Rosemarie Ford (Bombalurina) and Aeva May (Demeter) strut their stuff properly, and I can assure you they are way more sexy that anything Ms. Swift manages. Oh, and there’s Grizzabella: she’s not out on the street because she “went with McCavity”; she’s a sex worker. Tottenham Court Road was a red light district when Eliot wrote those poems. The whole narrative of the show is the redemption of a “fallen woman”.

I’m not best placed to opine on the quality of the music, but I do want to make a few quick comments. The original stage show had to make do with a 16-piece orchestra because of the size of the theatre. For the video Lloyd Webber went for a full orchestra, with mixed results. One of the joys of Cats is that it is an eclectic mix of musical styles and dance styles. The full orchestra is magnificent on “Memory”, which is basically a song from a Puccini opera. It is much less good on some of the more traditional musical theatre numbers such as “Mr. Mistoffelees”. The movie seems to have taken a more middle ground, which was a relief.

There’s a new song in the movie, “Beautiful Ghosts”, to take account for Victoria’s enhanced role. It is not very good. Taylor Swift, whom the credits say voices it rather than Francesa Hayward who plays Victoria, does not help. Also a whole bunch of people who are actors or comedians rather than singers are allowed to sing their own songs. Again this does not help. Robbie Fairchild as Munkustrap does a decent job, but part of me wishes they had chosen someone with a deeper voice for that role, or had someone else sing it. He doesn’t sound like the day-to-day leader of the Jellicles. I know this is just me falling for social stereotypes about what alpha males should sound like.

On now to the plot and characters. It is, of course, a minor miracle that there is a plot at all. Lloyd Webber’s original idea was just to set the poems to music. There was no plot until Valerie Eliot showed him and Trevor Nunn an unpublished poem called “Grizzabella: the Glamour Cat”. Somehow they managed to stitch together something that vaguely made sense, and thankfully that’s all that musicals need to do. The audience is there for the songs and dancing, not the story. Hollywood, it seems, wanted something more.

I rather liked the idea of making more use of Victoria. In the stage show she’s basically there to find a use for a principal ballerina. The movie keeps that, but also uses her narrative as a young cat dumped by her humans to act as our introduction to the Jellicles and their customs. Any science fiction or fantasy writer will be familiar with the idea of the outsider character who acts as the eyes of the reader. So far so good, but…

In the stage show, McCavity briefly tries to kidnap Deuteronomy, but it is all over very quickly and McCavity’s evil is always understood as being directed towards humans (and most importantly towards police dogs), not towards his fellow cats. If he was evil towards cats, Eliot would have made him foreign, like Growltiger’s Siamese enemies. The movie turns him into some sort of pantomime villain. Idris Elba does his best, but it really doesn’t work, and it is hard to see how any cat with any brain, let alone the great McCavity, would ever think that it would.

I am, of course, delighted that Mistoffelees has been made more of a hero.

James Cordon and Rebel Wilson are absolute disasters. Neither of them makes any serious attempt to play a cat, except when doing it for laughs. They play themselves in cat suits. They do have comedy roles, but these are both characters, not bumbling buffoons. Jennyanydots is more like Joyce Grenfell than the character Wilson plays, while Bustopher Jones is a very proper gentleman, not a messy glutton. I got the impression that what we had here were two people who thought they were too big for the show.

In contrast Ian McKellen and Judi Dench do much better jobs, despite being much bigger names. I still prefer John Mills as Gus. I guess that, having played Magneto and Gandalf, Sir Ian wanted something more dramatic and heroic than an old chap with the palsy.

Dame Judi has been part of the Cats family from the start. She was originally down to play both Grizzabella and Jennyanydots, but she snapped an Achilles tendon in rehearsals and had to be replaced at the last minute. It is lovely that she finally has a place in the show. Of course this meant a gender flip for Deuteronomy. That took a bass voice out of the show which hasn’t properly been replaced, though McCavity doesn’t actually sing himself in the stage show. I suspect that is one reason why I had such an issue with Mukustrap’s voice.

Judi did make an off-hand comment about her therefore being a trans Deuteronomy, and of course the papers ran with that. I don’t think that she meant any harm by it. However, everyone has completely overlooked the actual trans character in the story. Sexing cats isn’t always easy, and that is why one of the magic tricks that Mr. Mistoffelees is known for is producing seven kittens, much to the surprise of his humans. So Mistoffelees is canonically a transmasculine cat, in addition to now being a hero and Victoria’s love interest. That is one cool cat.

It is possible that the movie also gender-flipped Griddlebone. She was originally Growltiger’s girlfriend, but she’s also mentioned in McCavity’s song and the movie has added a character with that name as one of McCavity’s goons. It isn’t clear what gender that cat is.

Mungojerrie and Rumpleteazer are a hard act to pull off. The stage show had Bonnie Langford as Rumpleteazer, which will either please you or immediately set your teeth on edge. I’m in the latter camp. The video has some truly appalling cockney accents. (Jo Gibb, who plays Rumpleteazer, has a lovely Scottish accent, which I think she should have kept.) The movie, I think, comes closest to getting them right. They are very naughty, but they really don’t mean any harm.

I was pleased to see Growltiger had a place in the movie, because the much-feared pirate king of the Thames is a great character. Sadly the movie turned him into a bullying henchman for McCavity, which was a dreadful waste.

Jennifer Hudson did a fine job as Grizzabella. You can’t go far wrong with a voice like that. But the two stars of the show were the lead dancers. Francesca Hayward (Victoria) and Steven McRae (Skimbleshanks) are both Royal Ballet dancers. Victoria is the female lead and is in pretty much every scene. Hayward does a good job of acting in additional to showing off her ballet skills. McRae is also an expert tap dancer, and he puts this skill to good effect as Skimbleshanks, tap-dancing the sound of a train pulling away from a station and picking up speed. It is the one moment of absolute genius in the movie. I’d go to see it again just for that.

Of course I will see it again anyway. I love the musical, and the songs, and most of all it is a film about cats. I’m sorry that you humans are a bit perturbed about that, but how many movies do you have about apes compared to movies about us, hmm? I think it is about time we had our turn, praise be to Bastet. You can have Hollywood back soon, because after all that rushing around and excitement we will need to go sleep for several hours.

The new book from Jeff VanderMeer is set in the same universe as his novel, Borne.

The new book from Jeff VanderMeer is set in the same universe as his novel, Borne. They are not astronauts, of course. Except that one of them is. Grayson, a black woman, is the sole survivor of a doomed Moon colony who returned to Earth after all her colleagues had died. Grayson is also the only one of the Astronauts who is fully human.

They are not astronauts, of course. Except that one of them is. Grayson, a black woman, is the sole survivor of a doomed Moon colony who returned to Earth after all her colleagues had died. Grayson is also the only one of the Astronauts who is fully human.

I don’t often review graphic novels here, because I’m not sure I’m competent to do so. This one, however, is written by my Swedish friend, Sara B. Elfgren, and is gorgeously illustrated by Karl Johnsson. It is newly available in English translation, and comes with an enthusiastic blub from Mike Carey who knows far more about graphic novels than I do.

I don’t often review graphic novels here, because I’m not sure I’m competent to do so. This one, however, is written by my Swedish friend, Sara B. Elfgren, and is gorgeously illustrated by Karl Johnsson. It is newly available in English translation, and comes with an enthusiastic blub from Mike Carey who knows far more about graphic novels than I do.

Although I had the new Erin Morgenstern book before last issue, I elected not to try to read it in time. That’s partly because it is long so I wasn’t sure I’d get it finished. But also I didn’t want two books about doors and keys in the same issue. The Starless Sea and The Ten Thousand Doors of January both feature keys on the cover. Both feature heroes striving to keep doors to another world open while enemies try to close them forever. Thankfully there the similarities end.

Although I had the new Erin Morgenstern book before last issue, I elected not to try to read it in time. That’s partly because it is long so I wasn’t sure I’d get it finished. But also I didn’t want two books about doors and keys in the same issue. The Starless Sea and The Ten Thousand Doors of January both feature keys on the cover. Both feature heroes striving to keep doors to another world open while enemies try to close them forever. Thankfully there the similarities end.

Back in November, SF&F Twitter was all abuzz with

Back in November, SF&F Twitter was all abuzz with

There are some books that I can race through very quickly and write reviews of immediately. There are others where I have to think a lot while reading them and then let those thoughts marinate for a while before saying anything. Books by Karen Lord tend to be in the latter category.

There are some books that I can race through very quickly and write reviews of immediately. There are others where I have to think a lot while reading them and then let those thoughts marinate for a while before saying anything. Books by Karen Lord tend to be in the latter category.

I very much enjoyed Trail of Lightning, the debut novel from Rebecca Roanhorse which, among other things, won her the Award Then Known as the Campbell. I therefore picked up the sequel as soon as I found a copy. The books are part of a series called The Sixth World. They feature a seriously kickass woman called Maggie Hoskie who lives in a Drowned World near future North America. Colorado, being considerably above sea level, has survived the flood, and so has the Navajo nation.

I very much enjoyed Trail of Lightning, the debut novel from Rebecca Roanhorse which, among other things, won her the Award Then Known as the Campbell. I therefore picked up the sequel as soon as I found a copy. The books are part of a series called The Sixth World. They feature a seriously kickass woman called Maggie Hoskie who lives in a Drowned World near future North America. Colorado, being considerably above sea level, has survived the flood, and so has the Navajo nation.

This is not a new book. It was first published in 2014. It is, however, a gorgeous new edition which Oxford University Press have presumably issued to cash in on the current popularity of Norse myth.

This is not a new book. It was first published in 2014. It is, however, a gorgeous new edition which Oxford University Press have presumably issued to cash in on the current popularity of Norse myth.

I have great enjoyed the previous two volumes in Theodora Goss’s Athena Club series, and immediately pounced upon the new one, The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl, as soon as it became available. It follows directly on from European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman. Indeed, some of the Club’s members are still in Budapest when the book opens. The majority, however, have returned to Mary Jekyll’s London home, only to be told by their distraught housekeeper, Mrs. Poole, that Alice, the kitchen maid, has been abducted in the middle of the night by persons unknown.

I have great enjoyed the previous two volumes in Theodora Goss’s Athena Club series, and immediately pounced upon the new one, The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl, as soon as it became available. It follows directly on from European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman. Indeed, some of the Club’s members are still in Budapest when the book opens. The majority, however, have returned to Mary Jekyll’s London home, only to be told by their distraught housekeeper, Mrs. Poole, that Alice, the kitchen maid, has been abducted in the middle of the night by persons unknown.

I saw Cats in the theatre not long after it started. As I recall, Elaine Paige had moved on, but Brian Blessed and Bonnie Langford were still in it, as were most of the original cast. It was a fabulous experience. I know the soundtrack very well. So I was interested to see that there was going to be a movie, and not nearly as creeped out by the trailer as most people. Then the reviews started coming in, and it was clear that something had gone badly wrong. After all, this is a film of the longest-running musical in both London and New York. How could it tank so badly? As it happened, I had picked up the video of the stage show just before Christmas (HMV had it on sale), so I watched that, and then went to see the movie.

I saw Cats in the theatre not long after it started. As I recall, Elaine Paige had moved on, but Brian Blessed and Bonnie Langford were still in it, as were most of the original cast. It was a fabulous experience. I know the soundtrack very well. So I was interested to see that there was going to be a movie, and not nearly as creeped out by the trailer as most people. Then the reviews started coming in, and it was clear that something had gone badly wrong. After all, this is a film of the longest-running musical in both London and New York. How could it tank so badly? As it happened, I had picked up the video of the stage show just before Christmas (HMV had it on sale), so I watched that, and then went to see the movie.

This is another interview that was previously broadcast on Cheryl’s Women’s Outlook show on Ujima Radio.

This is another interview that was previously broadcast on Cheryl’s Women’s Outlook show on Ujima Radio.

Reviewing the final book in a series is always a challenging task as you want to talk about how the author has concluded the story arcs, and yet somehow avoid giving too many spoilers for the previous books. I’m not going to try very hard here, because there are few excuses for not reading Ian McDonald. You should be up to date.

Reviewing the final book in a series is always a challenging task as you want to talk about how the author has concluded the story arcs, and yet somehow avoid giving too many spoilers for the previous books. I’m not going to try very hard here, because there are few excuses for not reading Ian McDonald. You should be up to date.

The second of Kate Heartfield’s Alice Payne novellas, Alice Payne Rides, is a full-on time war story. That is, it engages directly with the seeming impossibility of winning a time war when one side or the other can always go back in time to undo things. This may make the plot a little over-complicated for some readers, but you are all science fiction people so I’m sure the vast majority will be OK with it.

The second of Kate Heartfield’s Alice Payne novellas, Alice Payne Rides, is a full-on time war story. That is, it engages directly with the seeming impossibility of winning a time war when one side or the other can always go back in time to undo things. This may make the plot a little over-complicated for some readers, but you are all science fiction people so I’m sure the vast majority will be OK with it.

I missed reviewing Gareth L Powell’s Embers of War when it came out, but now that I have read Fleet of Knives as well I figure I can do both together. Ideally, perhaps, I should do the whole trilogy, but that would mean a longer wait and Gareth wouldn’t thank me for that.

I missed reviewing Gareth L Powell’s Embers of War when it came out, but now that I have read Fleet of Knives as well I figure I can do both together. Ideally, perhaps, I should do the whole trilogy, but that would mean a longer wait and Gareth wouldn’t thank me for that. By the end of the first book, Sal and the Trouble Dog have discovered another relic of the builders of the Gallery. The Fleet of Knives is a vast fleet of marble-white, dagger-shaped warships run entirely by AIs. Much of the book named after them deals with the consequences of unleashing such a potent military force on the galaxy.

By the end of the first book, Sal and the Trouble Dog have discovered another relic of the builders of the Gallery. The Fleet of Knives is a vast fleet of marble-white, dagger-shaped warships run entirely by AIs. Much of the book named after them deals with the consequences of unleashing such a potent military force on the galaxy.

I met Lania Knight at a creative writing conference at Bath Spa University earlier this year. It turned out that we had a few interests in common, including feminist science fiction. Knight had a novel published in 2018 through an American small press. Life happening and the press in question not being a science fiction specialist have conspired to causing the book to fly under the radar, so I offered to take a look at it.

I met Lania Knight at a creative writing conference at Bath Spa University earlier this year. It turned out that we had a few interests in common, including feminist science fiction. Knight had a novel published in 2018 through an American small press. Life happening and the press in question not being a science fiction specialist have conspired to causing the book to fly under the radar, so I offered to take a look at it.

It appears that this is a month for weirdly experimental fiction. If you thought that Jeff VanderMeer’s Dead Astronauts was odd, well you ain’t seen nothing yet.

It appears that this is a month for weirdly experimental fiction. If you thought that Jeff VanderMeer’s Dead Astronauts was odd, well you ain’t seen nothing yet.

We are truly living in a golden age of science fiction and fantasy television. Good Omens was delightful. The Expanse continues to go from strength to strength. Watchmen is an unexpected surprise. And in addition we have Philip Pullman adapting His Dark Materials for the BBC.

We are truly living in a golden age of science fiction and fantasy television. Good Omens was delightful. The Expanse continues to go from strength to strength. Watchmen is an unexpected surprise. And in addition we have Philip Pullman adapting His Dark Materials for the BBC.

“Truth eats lies just as the crocodile eats the moon”

“Truth eats lies just as the crocodile eats the moon”

All of Emma Newman’s previous books in the Planetfall series have been billed as being readable as stand-alones. The new book, Atlas Alone, may be the first to break that pattern. It is a direct sequel to After Atlas. If you are going to read it, it would be helpful to know who Carlos, Deanna and Travis are, and why they are on a starship heading after the Pathfinder. I’m going to assume that you folks know that. If you don’t, there will be spoilers.

All of Emma Newman’s previous books in the Planetfall series have been billed as being readable as stand-alones. The new book, Atlas Alone, may be the first to break that pattern. It is a direct sequel to After Atlas. If you are going to read it, it would be helpful to know who Carlos, Deanna and Travis are, and why they are on a starship heading after the Pathfinder. I’m going to assume that you folks know that. If you don’t, there will be spoilers.

Once upon a time…

Once upon a time…

Having a story told by one of the protagonists from his prison cell must be this year’s thing. Marlon James does it in Black Leopard, Red Wolf. Jenn Lyons does the same thing in The Ruin of Kings. Tracker, of course, is probably lying. It is what he does. We may have a better idea of the truth of the story when we hear the testimony of other members of his band. As for the prisoner in Lyons’ book, well…

Having a story told by one of the protagonists from his prison cell must be this year’s thing. Marlon James does it in Black Leopard, Red Wolf. Jenn Lyons does the same thing in The Ruin of Kings. Tracker, of course, is probably lying. It is what he does. We may have a better idea of the truth of the story when we hear the testimony of other members of his band. As for the prisoner in Lyons’ book, well…

OK, let’s get the awkward thing out of the way first. This is a fantasy novel written by a science fiction writer. That’s not to say it is a bad book. It is just that if you have certain expectations of a fantasy novel to do with it having a sense of the mysterious, the ethereal, the spiritual, then you will probably be disappointed. If instead you are happy to read a well-written book that speculates about the relationship between gods and men, you will be perfectly content with what Ann Leckie has to offer in The Raven Tower.

OK, let’s get the awkward thing out of the way first. This is a fantasy novel written by a science fiction writer. That’s not to say it is a bad book. It is just that if you have certain expectations of a fantasy novel to do with it having a sense of the mysterious, the ethereal, the spiritual, then you will probably be disappointed. If instead you are happy to read a well-written book that speculates about the relationship between gods and men, you will be perfectly content with what Ann Leckie has to offer in The Raven Tower.

Time travel is very much the thing these days, it seems. I loved Ian McDonald’s Time Was, and I recently read a very different time-crossed love story in Amal El-Mohtar & Max Gladstone’s This is How You Lose the Time War. I loved that one too. Kameron Hurley’s time travel story is a very different beast again, but also well worth reading.

Time travel is very much the thing these days, it seems. I loved Ian McDonald’s Time Was, and I recently read a very different time-crossed love story in Amal El-Mohtar & Max Gladstone’s This is How You Lose the Time War. I loved that one too. Kameron Hurley’s time travel story is a very different beast again, but also well worth reading.

P Djèlí Clark is rapidly becoming one of my favorite writers. His The Black God’s Drums was one of the stand-out novellas of 2018. It is set in New Orleans and has airship pirates, plus nuns with guns and chemistry labs. I mean, nuns with guns is quite terrifying enough; give them chemistry labs too and there’s no telling what they might get up to.

P Djèlí Clark is rapidly becoming one of my favorite writers. His The Black God’s Drums was one of the stand-out novellas of 2018. It is set in New Orleans and has airship pirates, plus nuns with guns and chemistry labs. I mean, nuns with guns is quite terrifying enough; give them chemistry labs too and there’s no telling what they might get up to.

You probably know by now that Charlie Jane Anders’ new novel, The City in the Middle of the Night, is set on a tidally locked planet. That is, the planet always presents the same side to its sun, just as our moon does to us, resulting in one side that it always day and another that is always night. Human settlers have to reside in the equatorial zone.

You probably know by now that Charlie Jane Anders’ new novel, The City in the Middle of the Night, is set on a tidally locked planet. That is, the planet always presents the same side to its sun, just as our moon does to us, resulting in one side that it always day and another that is always night. Human settlers have to reside in the equatorial zone.

One of the things that is fashionable in the publishing industry these days is to have an “elevator pitch” for your book. This is just a couple of lines describing your idea that you can pitch in a matter of seconds, perhaps where a decision maker is in an elevator with you and can’t escape.

One of the things that is fashionable in the publishing industry these days is to have an “elevator pitch” for your book. This is just a couple of lines describing your idea that you can pitch in a matter of seconds, perhaps where a decision maker is in an elevator with you and can’t escape.

Hmm, what have we here. Let’s see…

Hmm, what have we here. Let’s see…

We seem to be particularly blessed with debut novels this year (2019). I was hugely impressed with The Ruin of Kings in epic fantasy. Now it is the turn of space opera and A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine.

We seem to be particularly blessed with debut novels this year (2019). I was hugely impressed with The Ruin of Kings in epic fantasy. Now it is the turn of space opera and A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine.

What can you say about a new Guy Gavriel Kay novel? You read it, it is brilliant, you decide once again that Kay is a genius. Plus ça change. If you are a Kay fan then you will love A Brightness Long Ago. If you have never read him before you should probably start with Tigana or The Lions of Al Rassan. If you don’t like what Kay does, the new book will not change your mind.

What can you say about a new Guy Gavriel Kay novel? You read it, it is brilliant, you decide once again that Kay is a genius. Plus ça change. If you are a Kay fan then you will love A Brightness Long Ago. If you have never read him before you should probably start with Tigana or The Lions of Al Rassan. If you don’t like what Kay does, the new book will not change your mind.

There are plenty of people out there who absolutely love Erin Morgenstern’s debut novel, The Night Circus. There are others who think it is massively over-rated. I can see where both sets of people are coming from, and indeed I vacillated between the two views rather a lot when reading the book. How can a book have that sort of effect on people? Here’s a challenge for a reviewer.

There are plenty of people out there who absolutely love Erin Morgenstern’s debut novel, The Night Circus. There are others who think it is massively over-rated. I can see where both sets of people are coming from, and indeed I vacillated between the two views rather a lot when reading the book. How can a book have that sort of effect on people? Here’s a challenge for a reviewer.

Every so often a publisher does something that completely surprises you. Here’s a case in point. Solaris do some great books. They publish Gareth L Powell’s Ack-Ack Macaque books, and Juliet E McKenna’s latest Einarinn series. But both of these are very clearly genre novels. I did not expect them to come up with something they might want to submit to mainstream literary prizes and not feel they were wasting their time.

Every so often a publisher does something that completely surprises you. Here’s a case in point. Solaris do some great books. They publish Gareth L Powell’s Ack-Ack Macaque books, and Juliet E McKenna’s latest Einarinn series. But both of these are very clearly genre novels. I did not expect them to come up with something they might want to submit to mainstream literary prizes and not feel they were wasting their time.

This is the November 2019 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the November 2019 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Editorial – November 2019

Editorial – November 2019 The Ten Thousand Doors of January

The Ten Thousand Doors of January The Future of Another Timeline

The Future of Another Timeline Infinite Detail

Infinite Detail The Rosewater Redemption

The Rosewater Redemption The Deep

The Deep Interview – Rivers Solomon

Interview – Rivers Solomon The Exile Waiting

The Exile Waiting Interview – Kathryn Allan

Interview – Kathryn Allan What Can WSFS Do?

What Can WSFS Do? The Forbidden Stars

The Forbidden Stars Silver in the Wood

Silver in the Wood BristolCon 2019

BristolCon 2019 Getting artwork for a fanzine cover can be a bit challenging. I’m very much aware that artists should be paid for their work, but fanzines typically don’t bring in any money, let alone enough to pay decent usage fees. Thankfully there are people out there who put good quality art up with Creative Commons licences. This one is by Steve Bidmead and you can find the original

Getting artwork for a fanzine cover can be a bit challenging. I’m very much aware that artists should be paid for their work, but fanzines typically don’t bring in any money, let alone enough to pay decent usage fees. Thankfully there are people out there who put good quality art up with Creative Commons licences. This one is by Steve Bidmead and you can find the original  Alix E Harrow is not a necromancer from the Ninth House, though she may sound like it from her name. Nor does she appear to have a thing about bones. She does, however, appear to have a thing about doors. This year she won the Short Story Hugo for something called, “A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies”. Her debut novel is called The Ten Thousand Doors of January.

Alix E Harrow is not a necromancer from the Ninth House, though she may sound like it from her name. Nor does she appear to have a thing about bones. She does, however, appear to have a thing about doors. This year she won the Short Story Hugo for something called, “A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies”. Her debut novel is called The Ten Thousand Doors of January.

Well, here we go again, this is yet another time war story.

Well, here we go again, this is yet another time war story.

One of the things I love about the current internationalisation of science fiction is the fact that we can read books by people who understand others places far better than we white Westerners do. I still love Ian McDonald’s books set in Kenya, India, Brazil and Turkey, and I think that they were a necessary step on the journey that our community has undertaken over the past couple of decades, but now we can have the real thing. We can read Silvia Morena Garcia writing about Mexico, Aliette de Bodard exploring Vietnamese culture, Tasha Shuri introducing us to India, and many fine writers from China and Nigeria. What distinguishes them all is their in-depth understanding of their settings.

One of the things I love about the current internationalisation of science fiction is the fact that we can read books by people who understand others places far better than we white Westerners do. I still love Ian McDonald’s books set in Kenya, India, Brazil and Turkey, and I think that they were a necessary step on the journey that our community has undertaken over the past couple of decades, but now we can have the real thing. We can read Silvia Morena Garcia writing about Mexico, Aliette de Bodard exploring Vietnamese culture, Tasha Shuri introducing us to India, and many fine writers from China and Nigeria. What distinguishes them all is their in-depth understanding of their settings.

I need to start this review by saying that it will inevitably contain spoilers for Rosewater. It is pretty much impossible to talk about the new book without explaining what Rosewater is. There will also be mention of some of the major characters of the first book. So if you haven’t read Rosewater, go out and do that now. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

I need to start this review by saying that it will inevitably contain spoilers for Rosewater. It is pretty much impossible to talk about the new book without explaining what Rosewater is. There will also be mention of some of the major characters of the first book. So if you haven’t read Rosewater, go out and do that now. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Many of you will recall that Rivers Solomon’s new novella, The Deep, is based on the Hugo-finalist clipping song of the same name. It is a story about a race of marine creatures who are descended from pregnant African women thrown overboard from slave ships. I interviewed Solomon about the book last year and have included that interview in the issue. I’m delighted to see that the book is finally out. Here’s the song as a reminder.

Many of you will recall that Rivers Solomon’s new novella, The Deep, is based on the Hugo-finalist clipping song of the same name. It is a story about a race of marine creatures who are descended from pregnant African women thrown overboard from slave ships. I interviewed Solomon about the book last year and have included that interview in the issue. I’m delighted to see that the book is finally out. Here’s the song as a reminder.