Most of you will be familiar with the furore surrounding the “Attack Helicopter” story in Clarkesworld. I don’t discuss that story here. Both Neil Clarke and the author, Isabel Fall, know that they stepped into a minefield there, and I am sure they have learned lessons, but I do want to talk about the minefield.

Most of you will be familiar with the furore surrounding the “Attack Helicopter” story in Clarkesworld. I don’t discuss that story here. Both Neil Clarke and the author, Isabel Fall, know that they stepped into a minefield there, and I am sure they have learned lessons, but I do want to talk about the minefield.

One of the reasons that this issue blew up is that well-meaning people, both cis and trans, wanted to be able to tell interesting and edgy stories about the trans experience. Writing interesting and edgy stories is what good writers want to do, and what good editors want to publish. However, there are things that I, as a trans woman, would not want to write about, either in fiction or nor fiction, because doing so would cause way too much trouble for me, and for others. I want to explain what some of those things are, and why they are so problematic.

I should start by saying that there are no hard and fast rules here. What you can get away with in writing for a trans-themed anthology from a small press is very different to what you can do in a high-profile venue such as Clarkesworld. There are plenty of great stories in the Transcendent anthologies, many of which came from small presses. Who you are also matters. I continue to be amazed that Charlie Jane Anders got away with writing “Don’t Press Charges and I Won’t Sue”. Personally, I would not have had the mental fortitude, let along the literary talent, to write that story. But it also touched on some of the issues I will mention here. I presume that one of the reasons there was no great backlash against it is that Charlie Jane was already a hugely respected writer, and openly trans, when it was published.

That said, few of us have the stature of Charlie Jane. We have to be careful, and there are a variety of reasons for that.

One issue that trans people face these days is that we are the focus of a great deal of interest from the media and right-wing political activists. It is far worse in the UK than anywhere else, but the international nature of social media means that no one is safe. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I know that everything that I write online is scrutinised by anti-trans extremists looking for excuses to initiate a social media pile on, to have me banned from platforms, or to pass to their friends in the media as the basis for another “trans outrage” article. I note that the right-wing media are already using the Clarkesworld affair as an excuse to portray trans people as aggressive and intolerant.

In view of the fact that we are so often portrayed as monsters in the popular imagination, one thing I would be reluctant to do is write a story with a trans person as a villain. To start with there’s really no need. There are plenty of such stories out there, all of them intended to incite hatred against us, or simply using our alleged status as outsiders, as “freaks”, and as mentally ill. If you need an explanation as to why someone might be a serial killer, making that person trans is still an acceptable and common tactic in many circles.

That said, having a trans person as a villain is probably preferable to yet another transition story. Yes, I know that the one thing that is endlessly fascinating to cis people is the story of a man becoming a woman. (Much less so the other way around. Ask yourselves why that might be so.) But transition stories have been done to death, mostly badly, and frankly they aren’t that interesting to us unless we are currently embarking on that journey. Transition is a relatively short part of any trans person’s life. It is also a deeply traumatic one. That obviously makes for good fiction, but see below for why we shouldn’t go there.

What I want out of fiction is not stories about the transition process, but stories about trans people living their lives. After all, the whole point of transition is to move away from the trauma of being forced to live a lie and get on with being you. The standard trans narrative, as peddled by the media, is that life post-transition is no happier, and probably much worse, than it was before, because no one will ever accept you. The reality is very different. Trans people have all sorts of interesting and successful lives. And even if they are just dull and boring, that’s far better than the media would have you believe. We need more stories where some of the characters just happen to be trans.

However, the main topic that I would avoid as a trans writer is anything to do with the nature of transness itself. We are curious monkeys, we like to have explanations of things. Faced with the reality of trans people, it is entirely natural to ask, “why?” Cis people are not alone in this. Every trans person I have discussed this issue with would love to know why we are the way we are. The inconvenient truth is that no one knows. And the smart folks among us know that we shouldn’t be asking.

When I do trans awareness courses for clients I have to talk about this. There are all sorts of theories as to why people are trans. Some are biological in nature, and some psychological. None of them has any basis in experimental results. The only thing that we know for certain is that no one seems able to cure anyone of being trans. (Charlie Jane’s story was all about someone discovering the means to do so.)

The point I make to my classes is that there might not be a simple answer. In fact there almost certainly isn’t. The processes that make someone assigned male at birth a trans woman might be very different from the processes that make someone assigned female at birth a trans man; and both might be different from why anyone is non-binary, in any of the many ways that people can be non-binary. So picking any single, simple explanation pretty much guarantees that you will be wrong as far as large parts of the trans community is concerned. Speculation about simple explanations therefore does no one any good. And long term, if an explanation is found, Charlie Jane’s story eloquently details the awful consequences that will result for trans people.

Nevertheless, cis people continue to obsess over why people might be trans. The anti-trans brigade, for whom it is an article on faith that trans people cannot “really” exist, are forever on the lookout for an excuse to have us labelled insane once again. Any fiction that purports to explain transness therefor becomes fodder for their speculation.

As for the trans community, many of us would rather not be trans. Life would be so much easier if we were not. Young trans people can spend years agonising over the transition decision (I know I did). Everyone tells you what an awful mistake it will be. Your family, in particular, will probably be desperate for you not to do it. And yet eventually you will reach a point where life is no longer liveable if you don’t transition.

The inevitable result of all this is that trans people are also obsessed with the question of why they are trans. No one can ever know for certain, but many of us will find an explanation that works for us. That explanation may become a core part of our identity. It is something that you can cling to as justification for everything you are doing, in particular the pain that you are told you have caused your nearest and dearest.

But of course there is no explanation. There are lots of theories, but none of them work for everyone, and many of them are contradictory. Everyone’s experience of being trans is different, and consequently any story that discusses the nature of the trans experience will speak directly and personally to some trans people; and will painfully invalidate the experiences of others.

This would not be such a serious problem if trans people were not so much under siege. However, that is where we are. Pretty much the whole of the trans community is feeling very vulnerable right now. Therefore anything that appears to be attacking the validity of people’s experiences is going to cause a huge fuss. That is what appears to have happened in the case of the Clarkesworld story.

There are ways around this. It is safer to experiment in less high-profile venues. It is safer to experiment if you already have a reputation for writing good stories about trans people. If you have plenty of space in a story, you can have a variety of trans characters who have different experiences. But it is all still very risky and the temptation to self-censor is very strong.

This is the March 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the March 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Cover: The Thief’s Gamble: This issue's cover is The Thief's Gamble by Geoff Taylor

Cover: The Thief’s Gamble: This issue's cover is The Thief's Gamble by Geoff Taylor Comet Weather: A review of Comet Weather, the new contemporary fantasy novel from Liz Williams

Comet Weather: A review of Comet Weather, the new contemporary fantasy novel from Liz Williams Dark and Deepest Red: A review of Dark and Deepest Red, a YA fairy tale re-telling from Anne-Marie McLemore

Dark and Deepest Red: A review of Dark and Deepest Red, a YA fairy tale re-telling from Anne-Marie McLemore Mars: A review of the short story collection, Mars, by Croatian writer, Asja Bakić, translated by Jennifer Zoble

Mars: A review of the short story collection, Mars, by Croatian writer, Asja Bakić, translated by Jennifer Zoble Conventions Go Virtual: What does the sudden need to hold major events online mean for Worldcon? Cheryl has opinions.

Conventions Go Virtual: What does the sudden need to hold major events online mean for Worldcon? Cheryl has opinions. Star Trek: Picard: A review of the first season of the new Star Trek series featuring the return of Jean-Luc Picard

Star Trek: Picard: A review of the first season of the new Star Trek series featuring the return of Jean-Luc Picard Beneath the Rising: A review of Beneath the Rising, a decidedly weird tale of Tentacled Things by Premee Mohamed

Beneath the Rising: A review of Beneath the Rising, a decidedly weird tale of Tentacled Things by Premee Mohamed Interview – Juliet E. McKenna: An audio interview with author, Juliet E. McKenna

Interview – Juliet E. McKenna: An audio interview with author, Juliet E. McKenna The Golden Key: A review of The Golden Key, a debut fantasy novel about Victorian spiritualsts and faeries, by Marian Womack.

The Golden Key: A review of The Golden Key, a debut fantasy novel about Victorian spiritualsts and faeries, by Marian Womack. The Unspoken Name: A review of The Unspoken Name, a debut fantasy novel by AK Larkwood

The Unspoken Name: A review of The Unspoken Name, a debut fantasy novel by AK Larkwood The City of a Thousand Feelings: A review of The City of a Thousand Feelings, a novella by Anya Johanna DeNiro

The City of a Thousand Feelings: A review of The City of a Thousand Feelings, a novella by Anya Johanna DeNiro Editorial – March 2020: Cheryl explains how busy life is for her in self-isolation.

Editorial – March 2020: Cheryl explains how busy life is for her in self-isolation. For this issue’s cover I have used the cover of Juliet McKenna’s The Thief’s Gamble, which we have just brought back into paper at Wizard’s Tower. It is one of five books in the Tales of Einarinn series, all of which are

For this issue’s cover I have used the cover of Juliet McKenna’s The Thief’s Gamble, which we have just brought back into paper at Wizard’s Tower. It is one of five books in the Tales of Einarinn series, all of which are

Thanks to the idiocies of mainstream publishing we haven’t seen much from Liz Williams of late. Fortunately, the excellent Ian Whates and NewCon Press have coaxed her back into the saddle again, and the most recent result is Comet Weather. This looks like being the start of a new and interesting contemporary fantasy series.

Thanks to the idiocies of mainstream publishing we haven’t seen much from Liz Williams of late. Fortunately, the excellent Ian Whates and NewCon Press have coaxed her back into the saddle again, and the most recent result is Comet Weather. This looks like being the start of a new and interesting contemporary fantasy series.

Imaginative fairy tale re-tellings are a staple of fantasy these days, and this book is very much in that vein. Dark and Deepest Red takes as its starting point the deeply disturbing Hans Christian Andersen tale, “The Red Shoes”, in which a vain young girl becomes possessed by her beautiful footwear. This story takes that basic idea of magical shoes, but connects them instead to an actual historical event, the famous dancing plague that hit Strasbourg in 1518.

Imaginative fairy tale re-tellings are a staple of fantasy these days, and this book is very much in that vein. Dark and Deepest Red takes as its starting point the deeply disturbing Hans Christian Andersen tale, “The Red Shoes”, in which a vain young girl becomes possessed by her beautiful footwear. This story takes that basic idea of magical shoes, but connects them instead to an actual historical event, the famous dancing plague that hit Strasbourg in 1518.

A few weeks ago, when travel was a normal thing, I went to London for a meeting. The venue happened to be near Piccadilly Circus, so I took the opportunity to visit a shop I wanted to support.

A few weeks ago, when travel was a normal thing, I went to London for a meeting. The venue happened to be near Piccadilly Circus, so I took the opportunity to visit a shop I wanted to support.

Regular readers will know that I have long been an advocate of getting more people involved in conventions, in particular Worldcon. It seems crazy to me that we should get a few thousand people attending the event each year, only to then up and hold it in a completely different part of the world the following year and provide no easy means for them to take part. Most people simply can’t afford to go to Worldcon wherever it is in the world, and that seriously restricts people’s loyalty to the event.

Regular readers will know that I have long been an advocate of getting more people involved in conventions, in particular Worldcon. It seems crazy to me that we should get a few thousand people attending the event each year, only to then up and hold it in a completely different part of the world the following year and provide no easy means for them to take part. Most people simply can’t afford to go to Worldcon wherever it is in the world, and that seriously restricts people’s loyalty to the event. We all knew that this was going to be an exercise in nostalgia. Jean-Luc Picard would probably win any poll of favourite Star Trek captains hands-down, and Patrick Stewart is a superb actor who has gone on to wow the geek community in other roles as well. In some ways, therefore, it was a project that had no risks. All it had to do was deliver fan service.

We all knew that this was going to be an exercise in nostalgia. Jean-Luc Picard would probably win any poll of favourite Star Trek captains hands-down, and Patrick Stewart is a superb actor who has gone on to wow the geek community in other roles as well. In some ways, therefore, it was a project that had no risks. All it had to do was deliver fan service. Well, this is a weird one. That’s a compliment, of course.

Well, this is a weird one. That’s a compliment, of course.

With the paper re-issues of the Tales of Einarinn series rolling out from Wizard’s Tower this month, I took the opportunity to interview Juliet about the project. Other topics discussed include

With the paper re-issues of the Tales of Einarinn series rolling out from Wizard’s Tower this month, I took the opportunity to interview Juliet about the project. Other topics discussed include  Well, here’s an interesting one. The Golden Key is a debut fantasy from Marian Womack. It is being very heavily promoted by the publisher, Titan. And by “very heavily” I mean adverts on the Tube sort of expenditure. It also has a rave recommendation from Cat Valente who was one of Womack’s teachers at Clarion. That’s a heck of a lot to live up to.

Well, here’s an interesting one. The Golden Key is a debut fantasy from Marian Womack. It is being very heavily promoted by the publisher, Titan. And by “very heavily” I mean adverts on the Tube sort of expenditure. It also has a rave recommendation from Cat Valente who was one of Womack’s teachers at Clarion. That’s a heck of a lot to live up to.

This one took a little getting in to. The Unspoken Name is a debut fantasy novel by AK Larkwood. It is a large tome, and begins as if it is going to be very serious, and possibly a bit gloomy. Our hero, Csorwe, is an adept in a religious cult known as The House of Silence, devoted to the worship of The Unspoken One.

This one took a little getting in to. The Unspoken Name is a debut fantasy novel by AK Larkwood. It is a large tome, and begins as if it is going to be very serious, and possibly a bit gloomy. Our hero, Csorwe, is an adept in a religious cult known as The House of Silence, devoted to the worship of The Unspoken One.

This is another book from the Aqueduct Press Conversation Pieces series. It is thus quite short. (I read it in a few hours one morning.) It is also definitely a conversation piece and what one might term “experimental”.

This is another book from the Aqueduct Press Conversation Pieces series. It is thus quite short. (I read it in a few hours one morning.) It is also definitely a conversation piece and what one might term “experimental”.

This is the February 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the February 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Agency

Agency The Light of Impossible Stars

The Light of Impossible Stars Maresi: Red Mantle

Maresi: Red Mantle To Be Taught if Fortunate

To Be Taught if Fortunate Vei — Volume 2

Vei — Volume 2 Watchmen — The TV Series

Watchmen — The TV Series The Rampant

The Rampant Picard — Countdown

Picard — Countdown

On a remote island in the Northern Seas there is a secret religious establishment. One might call it a nunnery, for it is staffed entirely by women. The Red Abbey, however, is not like any nunnery of our world. In the Red Abbey, even god is female.

On a remote island in the Northern Seas there is a secret religious establishment. One might call it a nunnery, for it is staffed entirely by women. The Red Abbey, however, is not like any nunnery of our world. In the Red Abbey, even god is female.

This is another piece of art from Pixabay. The artist is German and goes by the handle of 024-657-834. You can find the original image

This is another piece of art from Pixabay. The artist is German and goes by the handle of 024-657-834. You can find the original image

Two things are known to be hard. One is making the middle book of a trilogy interesting. Another is writing near future SF in a time of rapid social change. William Gibson has sailed straight into the storm created when these two problems collide.

Two things are known to be hard. One is making the middle book of a trilogy interesting. Another is writing near future SF in a time of rapid social change. William Gibson has sailed straight into the storm created when these two problems collide.

The final books of trilogies are often nervous-making experiences because you so much want the author to round off an intriguing story in a satisfying manner. For me that was doubly true for Light of Impossible Stars because Gareth Powell is a friend and I want him to do well. Thankfully he seems to have pretty much nailed it.

The final books of trilogies are often nervous-making experiences because you so much want the author to round off an intriguing story in a satisfying manner. For me that was doubly true for Light of Impossible Stars because Gareth Powell is a friend and I want him to do well. Thankfully he seems to have pretty much nailed it.

Trilogies seem to be something of a theme in this issue. William Gibson is in the middle of one; Gareth Powell has finished one; and here too is another book, three. The Red Abbey Chronicles, however, have a rather different structure to the other two.

Trilogies seem to be something of a theme in this issue. William Gibson is in the middle of one; Gareth Powell has finished one; and here too is another book, three. The Red Abbey Chronicles, however, have a rather different structure to the other two.

Up until now, Becky Chambers is someone whose work I have enjoyed, but not specifically sought out. Generally I would read her when other people voted her onto award ballots and I needed to have an opinion. To Be Taught if Fortunate has changed all that. I will now be buying new Becky Chambers books when they come out, because this is very good.

Up until now, Becky Chambers is someone whose work I have enjoyed, but not specifically sought out. Generally I would read her when other people voted her onto award ballots and I needed to have an opinion. To Be Taught if Fortunate has changed all that. I will now be buying new Becky Chambers books when they come out, because this is very good.

I was delighted to have been sent the second and final volume of Vei by Sara B Elfgren and Karl Johnsson. My

I was delighted to have been sent the second and final volume of Vei by Sara B Elfgren and Karl Johnsson. My

Long ago there was a very famous comics series that set the world alight because of its innovative treatment of the superhero genre. The writer on that series got rather grumpy about things and said he didn’t want there to be any sequels, adaptations, or any of the other nonsense that corporations like to produce off the back of a successful creation. The corporation took little notice of him.

Long ago there was a very famous comics series that set the world alight because of its innovative treatment of the superhero genre. The writer on that series got rather grumpy about things and said he didn’t want there to be any sequels, adaptations, or any of the other nonsense that corporations like to produce off the back of a successful creation. The corporation took little notice of him. Well there’s a thing. A new novella from Aqueduct Press set in a post-apocalyptic world in which the apocalypse in question is Sumerian gods returning to Earth. In theory the world should have been destroyed, but something has gone wrong and the expected Rapture has been delayed. In the meantime, lots of people are dying and ending up in the Plains of the Imperfect Dead, rather than in the Netherworld. Fortunately for us humans, one young girl from Decatur, Indiana has been receiving prophetic dreams. It is apparently up to Gillian, and her Best Friend Forever, Mel, to journey to the Netherworld, find a being known as The Rampant, and get the apocalypse re-started.

Well there’s a thing. A new novella from Aqueduct Press set in a post-apocalyptic world in which the apocalypse in question is Sumerian gods returning to Earth. In theory the world should have been destroyed, but something has gone wrong and the expected Rapture has been delayed. In the meantime, lots of people are dying and ending up in the Plains of the Imperfect Dead, rather than in the Netherworld. Fortunately for us humans, one young girl from Decatur, Indiana has been receiving prophetic dreams. It is apparently up to Gillian, and her Best Friend Forever, Mel, to journey to the Netherworld, find a being known as The Rampant, and get the apocalypse re-started.

It seems like almost everyone in my Twitter timeline is watching the new Picard TV series. We all love Jean-Luc, whether we are Star Trek fans or not. Quite a few people, however, including me, have been a bit confused, because the series assumes a level of fannish obsession with the Trek universe that most of us don’t share.

It seems like almost everyone in my Twitter timeline is watching the new Picard TV series. We all love Jean-Luc, whether we are Star Trek fans or not. Quite a few people, however, including me, have been a bit confused, because the series assumes a level of fannish obsession with the Trek universe that most of us don’t share.

This is the January 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the January 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Absolute Book

The Absolute Book The Ghurkha and the Lord of Tuesday

The Ghurkha and the Lord of Tuesday The Stories We Don’t Tell

The Stories We Don’t Tell The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance

The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance Some Hugo Thoughts

Some Hugo Thoughts The Lights Go Out in Lychford

The Lights Go Out in Lychford Shadows of the Short Days

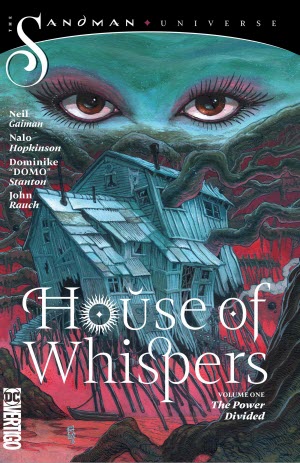

Shadows of the Short Days House of Whispers: Volume 1

House of Whispers: Volume 1 The Menace from Farside

The Menace from Farside Titans : Season 2

Titans : Season 2 Once again I have been scouring Pixabay for art that I can use freely. This issue’s cover is Robot Planet Moon by KellePics. There’s a donation link for the artist, so I chucked over a few bucks.

Once again I have been scouring Pixabay for art that I can use freely. This issue’s cover is Robot Planet Moon by KellePics. There’s a donation link for the artist, so I chucked over a few bucks.

I have been a fan of Elizabeth Knox for some time. I reviewed one of her books back in Emerald City days. But living in New Zealand is not good for a writing career. Going to conventions, or doing book tours, even in Australia, can be very expensive. Knox hasn’t had the support from publishers or readers that she deserves. Her latest novel, The Absolute Book, is available only from a

I have been a fan of Elizabeth Knox for some time. I reviewed one of her books back in Emerald City days. But living in New Zealand is not good for a writing career. Going to conventions, or doing book tours, even in Australia, can be very expensive. Knox hasn’t had the support from publishers or readers that she deserves. Her latest novel, The Absolute Book, is available only from a

Melek Ahmar, the Lord of Mars, the Red King, the Lord of Tuesday, Most August Rajah of Djinn has been asleep in a coffin in the Himalayas for over 4,000 years. Now he is awake and looking for a good party. But the world he finds himself in is very different than the one in which he was unfortunately bashed over the head while drunk. The humans, it seems, have been busy.

Melek Ahmar, the Lord of Mars, the Red King, the Lord of Tuesday, Most August Rajah of Djinn has been asleep in a coffin in the Himalayas for over 4,000 years. Now he is awake and looking for a good party. But the world he finds himself in is very different than the one in which he was unfortunately bashed over the head while drunk. The humans, it seems, have been busy.

Most of you will be familiar with the furore surrounding the “Attack Helicopter” story in Clarkesworld. I don’t discuss that story here. Both Neil Clarke and the author, Isabel Fall, know that they stepped into a minefield there, and I am sure they have learned lessons, but I do want to talk about the minefield.

Most of you will be familiar with the furore surrounding the “Attack Helicopter” story in Clarkesworld. I don’t discuss that story here. Both Neil Clarke and the author, Isabel Fall, know that they stepped into a minefield there, and I am sure they have learned lessons, but I do want to talk about the minefield. It has taken me a while to work through this show on Netflix because I kept getting distracted by other things (Good Omens, Picard, etc.). However, I have now seen the whole thing and I’m glad I did. Like most people of my, ahem, advanced years, I greatly enjoyed the movie despite the cheesy plot because the look of the thing was amazing, and because the Chamberlain was such a sleazy villain.

It has taken me a while to work through this show on Netflix because I kept getting distracted by other things (Good Omens, Picard, etc.). However, I have now seen the whole thing and I’m glad I did. Like most people of my, ahem, advanced years, I greatly enjoyed the movie despite the cheesy plot because the look of the thing was amazing, and because the Chamberlain was such a sleazy villain. Well, it is that time of year again. Voting is open, and there is a nominations ballot to be filled out. What have I actually read?

Well, it is that time of year again. Voting is open, and there is a nominations ballot to be filled out. What have I actually read? Paul Cornell’s Lychford series is one of several very successful novella collections produced by Tor.com. They are also probably the most connected to the real world. The stories are set in a small country town in England. Three women, one of whom is the local vicar, battle against supernatural threats. Now it so happens that Paul and his wife, Caroline, live in a small country town in England. She is the local vicar. So Cornell is very much writing what he knows. I sometimes worry what the people of Fairford in Gloucestershire think about these books, and how many have found themselves as minor characters. But Paul and Caroline have not been hounded out of the town yet, so I guess all is well.

Paul Cornell’s Lychford series is one of several very successful novella collections produced by Tor.com. They are also probably the most connected to the real world. The stories are set in a small country town in England. Three women, one of whom is the local vicar, battle against supernatural threats. Now it so happens that Paul and his wife, Caroline, live in a small country town in England. She is the local vicar. So Cornell is very much writing what he knows. I sometimes worry what the people of Fairford in Gloucestershire think about these books, and how many have found themselves as minor characters. But Paul and Caroline have not been hounded out of the town yet, so I guess all is well.

Well, that was grim. I’d hesitate to describe this book at Grimdark because that suggests big mediaeval battles in which everyone dies. Lots of people do die in Shadows of the Short Days, but mainly because they are innocent bystanders. Besides, the book is absolutely not mediaeval fantasy; it is more like a steampunk political thriller.

Well, that was grim. I’d hesitate to describe this book at Grimdark because that suggests big mediaeval battles in which everyone dies. Lots of people do die in Shadows of the Short Days, but mainly because they are innocent bystanders. Besides, the book is absolutely not mediaeval fantasy; it is more like a steampunk political thriller.

Now that Neil Gaiman is Very Hot Property, DC are keen to make as much of the IP he created as possible. There is a Sandman TV series coming, which Gaiman will have some role in, but he doesn’t have much time for writing comics. Therefore we have the Sandman Universe series of comics. They feature the setting and characters that Gaiman created, and he has some level of script control, but the writers are people he has hand-picked to carry on his legacy. I was delighted that one of the people he picked was Nalo Hopkinson.

Now that Neil Gaiman is Very Hot Property, DC are keen to make as much of the IP he created as possible. There is a Sandman TV series coming, which Gaiman will have some role in, but he doesn’t have much time for writing comics. Therefore we have the Sandman Universe series of comics. They feature the setting and characters that Gaiman created, and he has some level of script control, but the writers are people he has hand-picked to carry on his legacy. I was delighted that one of the people he picked was Nalo Hopkinson.

I have been a big fan of Ian McDonald’s Luna series (or Dallas on the Moon, as it is often known). Therefore when I heard that there was novella available in the same setting I had to get hold of a copy. The Menace from Farside is set somewhat earlier that the dramatic events of the novels, but it is very much in the same vein.

I have been a big fan of Ian McDonald’s Luna series (or Dallas on the Moon, as it is often known). Therefore when I heard that there was novella available in the same setting I had to get hold of a copy. The Menace from Farside is set somewhat earlier that the dramatic events of the novels, but it is very much in the same vein.

As you probably know, I am a sucker for superhero stories. However, I am mainly a Marvel reader. I know who the major DC characters are, but there are many others who are a complete mystery to me. I was therefore able to approach the Titans series on Netflix unencumbered with too much knowledge of how things “should” be. While the series made use of a whole bunch of standard Teen Titans characters, it also did its own thing. I was intrigued enough to watch it through, and was especially impressed by the final episode in which the demon, Trigon, who is the main villain of the season, gets inside Dick Grayson’s head and works out all of his frustrations about Batman.

As you probably know, I am a sucker for superhero stories. However, I am mainly a Marvel reader. I know who the major DC characters are, but there are many others who are a complete mystery to me. I was therefore able to approach the Titans series on Netflix unencumbered with too much knowledge of how things “should” be. While the series made use of a whole bunch of standard Teen Titans characters, it also did its own thing. I was intrigued enough to watch it through, and was especially impressed by the final episode in which the demon, Trigon, who is the main villain of the season, gets inside Dick Grayson’s head and works out all of his frustrations about Batman.

This is the December 2019 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the December 2019 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Dead Astronauts

Dead Astronauts The Starless Sea

The Starless Sea The Dragon Waiting

The Dragon Waiting Storm of Locusts

Storm of Locusts The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl

The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl Incarnations of Cats

Incarnations of Cats Interview – Kate Macdonald

Interview – Kate Macdonald Alice Payne Rides

Alice Payne Rides Remnant

Remnant The Taiga Syndrome

The Taiga Syndrome His Dark Materials – Season 1

His Dark Materials – Season 1 Once again I have been scouring the internet for artwork that is tagged with permission to use with modification. There is plenty of stuff out there, of course, but it isn’t all good, and crucially much of it won’t work as a magazine (or book) cover. There needs to be space to add text, and an awful lot of the art you can find online doesn’t have that.

Once again I have been scouring the internet for artwork that is tagged with permission to use with modification. There is plenty of stuff out there, of course, but it isn’t all good, and crucially much of it won’t work as a magazine (or book) cover. There needs to be space to add text, and an awful lot of the art you can find online doesn’t have that.