Wait, what? A Worldcon report already? It hasn’t even started yet. Well no, but social media has been full of outrage already, so I wanted to look at the issues raised.

Wait, what? A Worldcon report already? It hasn’t even started yet. Well no, but social media has been full of outrage already, so I wanted to look at the issues raised.

I should start by saying that I don’t want anything here to be taken as criticism of CoNZealand. What they have had to do is unprecedented, and that they have produced a convention at all is remarkable. Hopefully, however, the pain that they, and indeed the rest of the world, has had to endure because of the pandemic will leave us with a huge amount of valuable new information about how to run an online convention.

One of the issues that people have been complaining about is that this year, yet again, some Hugo finalists were left off programming, or asked to be on programme items that they knew nothing about. How do we keep making the same mistake year after year?

The first thing I want to note is that CoNZealand has somewhat less programming that a normal Worldcon. That means it is harder to give everyone the programme slots that they want. Lots of people probably think that with an online convention you can have as much programming as you want, but I suspect that it isn’t as easy as it seems. I’m hoping that after CoNZealand we’ll have a good idea of how much it costs to run an online event that can cope with a Worldcon-sized audience, what the timelines are, and so on.

Something else that is worth noting is that, having been made aware of the issue, CoNZealand has done something bold and innovative. They have given free attending passes to all Hugo finalists, and allowed them to buy full Attending Memberships for the price of a Supporting Membership. You might think that every Worldcon should do this, but in the past it would have been fairly pointless. A free membership is of no use if you can’t afford the cost of travel and accommodation, which is much higher.

This provides an interesting challenge for future Worldcons, assuming that in-person events are possible. Should they continue this new “tradition”? If so, does that commit them to providing at least some programming online? I’d like to see them do that.

The main issue, however, is the perennial question of why the same mistakes happen year after year. Is there no continuity? Do people not learn from what went before? There are, of course, some people who work on Worldcon in some capacity every year. Not all of them continue to work in the same area though. Also, working on Worldcon every year is much easier when the convention simply moves around North America. Doing that when it moves around the world is much harder.

Another issue is that, while the people working at lower levels may be the same year-on-year, the senior management team is largely new each time. Those are the positions that the local people want. What they don’t want is to have a bunch of foreigners come in and tell them what to do.

What it comes down to, is that the competitive nature of the site selection process often results in the bid being won by a group of people who are then determined to show they world what they can do. They want to put on their sort of convention, not do things the same way that the Americans do them. And that leads to a lot of reinventing the wheel.

There are other factors that prevent us having as much continuity as we would like, and I will come back to them later, but we have arrived at the other major issue that people have been complaining about: Site Selection.

The main focus of the controversy is the existence of a bid from Saudi Arabia, a country which more than half of regular Worldcon attendees ought to be very nervous of visiting. The issue is compounded by the existence of a bid for China for 2023, the folding of the Nice bid (who have lost their venue) and the fact that everyone who is not an American is suddenly very frightened about traveling to that country too.

It is rather ironic that, after years of fandom yelling about how Worldcon needs to visit other countries around the world, they are now yelling, “but not those countries”. That, however, is in large part a result of how the world has become so much less safe since 9/11. When I was much younger we would probably have approached the Saudi and Chinese bids with an attitude of, “yeah, let’s go there, and help the local fans do something that will annoy their oppressive governments.” No one is taking that line now.

There is a fair amount of privilege on display by those complaining, because for many people Worldcon has been hard to attend for years. There are people like myself and Peter Watts who are banned from travel to the USA. There are people who have Muslim-sounding names who are terrified of going through immigration to Western countries (including the UK). A number of African fans who wanted to attend the Irish Worldcon were unable to get visas. And of course the majority of fans around the world simply cannot afford to attend Worldcon at all, sometimes even if it is in their country.

Mostly, however, the outrage results from people not understanding how WSFS works. They assume that because the Saudi and Chinese bids exist, that someone in WSFS has approved those bids as suitable venues.

There is a job called Site Selection Administrator. This year it is held by my long-time friend from Melbourne, Alan Stewart. Should he have disallowed the Saudi bid? There are reasons why he can do so, but those reasons are based purely in factual issues such as does the bid have a contract with a venue. They do not include judgements such as, “does the country have a good record on civil rights?”

Maybe such a condition should exist. We could write such a rule into the WSFS Constitution. But how would it work in practice? Prospective bids, I am sure, would claim that their countries did have a good record to civil rights, especially compared to the USA which has hosted the majority of Worldcons in the past. What is the Site Selection Administrator to do then?

A good example of this sort of issue in practice is the administration of the Hugo Awards. In the past fandom has yelled at Hugo Administrators too. In particular, a lot of people said that it was wrong to allow the Puppies onto the final ballot. Hugo Administrators said that was down to the voters, and if they didn’t like the finalists they could always vote No Award, which they duly did. Worldcon might have got much less of a pasting in social media and the press if the Hugo Administrators had disqualified the Puppies, but then again they might have gone running to the media complaining about “cancel culture” and “no-platforming”. We can’t know.

This, however, is not the first time that people yelled at Hugo Administrators that they should have disqualified someone. Ten years earlier there was also massive outrage about a Hugo finalist. That was me. Lots of fans said that Emerald City, because it was distributed electronically rather than on paper, was not a proper fanzine. The Hugo Administrators refused to listen to them and allowed me to be on the ballot. And in 2004 Emerald City won Best Fanzine. Years later some people were still complaining that a “mistake” had been made and that my Hugo should be retrospectively taken away.

Now you may say that that’s a trivial example and of course they should have let me on the ballot. That’s what any sensible person would have done. And yet I was blacklisted from programming at the 2004 Worldcon, because the head of programming deemed that I was not a worthy Hugo finalist. If you put people in positions of power, they may abuse that ability.

The simple fact is that Hugo Administrators are afraid to disqualify anyone from the ballot, because they feel that if they did then they would be the focus of a fannish flame war with people claiming that they had acted unfairly. It is much easier for people to say, “let the voters decide”. That way you are off the hook.

I think that the same thing would happen with Site Selection. Sure, we could introduce rules about whether a country is a suitable place to be allowed to host a Worldcon. But Site Selection Administrators would be terrified of using that power. They would much rather say, “let the voters decide”, which is what happens now anyway.

Now there is a procedural issue here to do with what happens if None of the Above wins Site Selection. I will come back to that later, but first I want to address why people don’t seem to understand the “let the voters decide” argument when it is applied to Site Selection.

These days people understand the role of being a Hugo voter. They pay for the right, but it isn’t much if you just buy a Supporting Membership and you get the Voter Packet in return. But many of them don’t see being a Hugo voter as being synonymous with being a WSFS member. When it comes to Site Selection, they also don’t see themselves as WSFS members. Sometimes they don’t even understand that the “Voting Fee” that they are being asked to pay will in fact give them Hugo voting rights at whichever convention wins – something that they might have been planning to buy anyway.

Worse still, in addition to not seeing themselves as part of WSFS, that WSFS is not “Us”, they also seem convinced that WSFS is “Them”. That is, large numbers of fans seem convinced that there must be some secretive Board of Directors of WSFS who could, if they wanted, fix all the problems than fandom is exercised about. That “They” seemingly refuse to Do Something is the cause of much fannish ire on social media. But how are They supposed to Do Something if they don’t exist?

So why do Worldcons not explain all of this properly? Why don’t they just institute an annual membership fee for WSFS and have done with it? At this point we have to cue the ominous music, because I am about to mention the Great Fannish Shibboleth.

They don’t do that because they are terrified of it leading to WSFS Inc.

Way back in the early days of fandom, before even old timers like Kevin and myself got involved, there was a huge debate as to whether WSFS should incorporate, have a Board of Directors and so on. This idea was hugely controversial. That was partly because in those days fandom was very much influenced by American Libertarianism, but also the few non-American fans didn’t want the Americans telling them what to do all the time. Remember what I said earlier about non-American Worldcons wanting to do things their own way? Yeah, that.

A corporation was actually formed in 1956 and started to take action, but in 1958, Anna Moffatt, the first woman to chair a Worldcon, presided over a Business Meeting that effectively dissolved it. There were numerous attempts to resurrect the idea over the decades, all of which came to nothing. If you are interested in this history, it is available here.

Kevin, who arrived in fandom at the tail end of all this, tells me that he thinks official WSFS policy is that the Society should incorporate, but not yet. If ever the issue is raised, old time fans who were around in the 70’s are liable to yell “to the barricades” and head to the Business Meeting.

I wrote a lot more about what WSFS can and can’t do, and why, last year.

So WSFS is, in effect, an anarchist cooperative. That is “anarchist” in the literal sense of having no leaders. The only way that important decisions get taken is by putting them to the membership. Like other anarchist societies, WSFS is vulnerable to being unduly influenced by those who have the time, willingness and resources to participate in its governance. This is very different from a representative democracy, in which ordinary citizens elect representatives to do the governing on their behalf.

However, times change. What worked in the 1950s and 1960s may not be applicable decades later. It seems to me that a lot of the issues that fans are currently complaining about might be fixable if WSFS had some sort of central control.

A lot of the problems that we have with Worldcon these days is that everything has to be done from scratch by the current Worldcon committee. You need a large group of local fans prepared to do the work, and once they have done it they probably won’t have the energy to do so again for around 10 years. This severely restricts the number of places that can host a Worldcon.

If we had some sort of central control then we might (and I say “might” because I know it isn’t easy) be able to make a large part of Worldcon something that we can drop in anywhere in the world. That would probably involve a substantial amount of online programming. It would also mean that things like the Hugos and other WSFS functions would all be handled centrally, that Hugo finalists would automatically get a free Supporting Membership, and so on.

In particular it would mean that the online Hugo voting process could be centralised and not reinvented from scratch each year as seems to happen at the moment.

Part of that would probably mean having paid staff. Probably not full-time, at least to begin with, but there would be some sort of compensation for people prepared to devote part of their time to doing the same job on Worldcon year after year. Obviously WSFS would need money to pay for that, but a substantial amount of online programming that was accessible to Supporting Members could significantly increase revenue. Having staff who owe their allegiance to WSFS rather than to an individual Worldcon would do a lot to help knowledge retention and discourage reinventing the wheel.

The fact that WSFS members could have access to online programming would also help with the issue of people being unable to travel to Worldcon for a variety of reasons, including visa, personal safety and expense. That would mean that there would be less of an issue about where Worldcon was held.

In addition, if a WSFS Board did exist, then it could be responsible for deciding whether a bid was suitable. Joint corporate responsibility is much safer than asking a single, named individual to make such a decision. In practice they would have to do a lot more scrutiny because they would need to know that the drop-in aspects of Worldcon would work. There could still be competition for Site Selection, but the process of getting on the ballot could be more rigorous.

Hopefully such a system would also drastically reduce the cost of bidding, because for years now this has been a major problem. Running a Worldcon is hard enough, without exhausting and beggaring your fan base on bidding before you can even get started.

There could be a commitment to moving around the world. I think it would be a good thing to have Worldcon in an Arab country, though obviously Saudi Arabia is not a good choice right now. I’d like to see Worldcon in Brazil, though perhaps not while Bolsonaro is in charge, and India, though perhaps not while Modi is in charge.

For me, however, the main benefit of having some sort of central organisation is that fandom would have much more of a sense of ownership of WSFS. They would understand that they were WSFS members, and they would see WSFS as “Us” rather than “Them”.

On the other hand, implementing this would not be easy. The arguments against WSFS Inc still have a lot of validity. We can see good and bad examples out in the world. SFWA, I think, has done an excellent job in becoming more democratic and responsive to the requirements of its members. It is also getting good at running an annual conference, though admittedly it only has to do it in within North America. World Fantasy, on the other hand, is a glaring example of how things can go very wrong when the organisation is controlled by a small number of people who tend to be very conservative and can’t easily be held to account.

Let’s return now to that question of what happens if none of the bids for a particular year is acceptable to fandom. Right now the decision would be left up to the Business Meeting. This strikes me as a recipe for disaster, because a small group of fans could potentially overrule the desires of a much larger group. But, if we had a core Worldcon that we could drop in anywhere, then in a year where no site is acceptable we could just run that as a purely virtual con, and not have to skip a year or choose an unsuitable site.

This would also provide a useful backup option if circumstances change in the two years between Site Selection and the convention. It used to be that we expected the world to carry on in much the same way for years to come, but right now I would not be surprised to see the UK descend into civil unrest before 2024 and the expected Glasgow Worldcon. Civil unrest in the USA has clearly already started.

Talking of the Business Meeting, I am well aware that changing the WSFS Constitution is a slow and painful process. But there are things that could be done without BM approval. DC and Chicago (because Chicago will win, despite all of the worries about the Saudi bid) could both commit to providing an online element to their programming. They could also commit to working together to create elements of the convention that could be passed on to successor conventions. I know that’s extra work, but if we want Worldcon to have a future it is work that needs to be done. If it doesn’t get done then I’m sure that fans will start organising online international conventions in competition to Worldcon. Or someone with money will step in and create a commercial event.

This, then, is only the start of the discussion. I want to fix the problems with Worldcon, but I believe that fundamental change is necessary, and we’ll never fix anything if the discussion around how to fix things only ever happens on social media for a few weeks a year around when Worldcon happens. (We were talking a lot about the potential problems of the China bid this time last year. Has everyone forgotten?) I certainly don’t have all the answers, and I’m sure that there will be things I have missed in this article.

So I’m writing this now, during Worldcon, in the hope that people will start discussing it at the convention (i.e. on Discord). I’m also hoping that other fanzines will take up the baton and offer their own ideas as to how to fix things (not just complain that things are broken and that “They” must fix them). Most importantly, we need discussion as to how such a version of WSFS would be governed, but that’s a job for Kevin, not me.

Lockdown happened in sufficient time for this year’s NASFiC to be cancelled. However, perhaps as a result of the success of CoNZealand’s virtual programming, the committee decided at the last minute to try something virtual. It was all a bit of a rush, but it worked fairly well.

Lockdown happened in sufficient time for this year’s NASFiC to be cancelled. However, perhaps as a result of the success of CoNZealand’s virtual programming, the committee decided at the last minute to try something virtual. It was all a bit of a rush, but it worked fairly well.

This one was not on my radar at all, but I noticed a few people enthusing about it on social media and decided to give it a try. I’m very glad that I did.

This one was not on my radar at all, but I noticed a few people enthusing about it on social media and decided to give it a try. I’m very glad that I did.

This is another one of the novellas being published by Ian Whates’ NewCon Press. It is something of a departure for Ken MacLeod. He’s mostly known for writing highly political science fiction. What is he doing writing a love story about selkies?

This is another one of the novellas being published by Ian Whates’ NewCon Press. It is something of a departure for Ken MacLeod. He’s mostly known for writing highly political science fiction. What is he doing writing a love story about selkies?

This was not one of Supergirl’s best years. Following the intensely political season 4 was always going to be hard, and the season had other major problems to cope with, so I’m actually very relieved that it has been renewed for a 6th season.

This was not one of Supergirl’s best years. Following the intensely political season 4 was always going to be hard, and the season had other major problems to cope with, so I’m actually very relieved that it has been renewed for a 6th season.

This is the July 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the July 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again

The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again Mordew

Mordew The Empress of Salt and Fortune

The Empress of Salt and Fortune Pre-Worldcon Report

Pre-Worldcon Report Scarlet Odyssey

Scarlet Odyssey Of Dragons, Feasts and Murders

Of Dragons, Feasts and Murders Doom Patrol

Doom Patrol Exhalation

Exhalation Editorial – July 2020

Editorial – July 2020 This issues cover is another free piece of art from Pixabay. This one is called Blue Night Sky. It isn’t quite an image of the Southern Cross but it will have to do.

This issues cover is another free piece of art from Pixabay. This one is called Blue Night Sky. It isn’t quite an image of the Southern Cross but it will have to do.

The term ‘Matter of Britain’ is usually applied to Arthurian literature. I suspect that M John Harrison would be horrified if he thought I had accused him of writing an Arthurian novel, and yet his latest novel, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, is very much about the matter of Britain.

The term ‘Matter of Britain’ is usually applied to Arthurian literature. I suspect that M John Harrison would be horrified if he thought I had accused him of writing an Arthurian novel, and yet his latest novel, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, is very much about the matter of Britain.

Welcome to the city of Mordew. It is approximately semi-circular in shape. The base is bounded by massive mountains riddled with mines. The arc is formed by the Sea Wall which prevents the city from being flooded. Within the Sea Wall are slums, populated by the city’s poorest, whose streets run with Living Mud in which all sorts of vile creatures may be found/created. Within them is the walled Merchant Quarter, and within that the domain of the aristocracy. Right in the centre, high on the city’s only hill and reachable only via the spiralling, jet black Glass Road, is the Manse of the Master of Mordew, whose sorcerous powers keep the entire city running, and subservient to his whims.

Welcome to the city of Mordew. It is approximately semi-circular in shape. The base is bounded by massive mountains riddled with mines. The arc is formed by the Sea Wall which prevents the city from being flooded. Within the Sea Wall are slums, populated by the city’s poorest, whose streets run with Living Mud in which all sorts of vile creatures may be found/created. Within them is the walled Merchant Quarter, and within that the domain of the aristocracy. Right in the centre, high on the city’s only hill and reachable only via the spiralling, jet black Glass Road, is the Manse of the Master of Mordew, whose sorcerous powers keep the entire city running, and subservient to his whims. Well, here is a discovery. The Empress of Salt and Fortune is a novella by Nghi Vo. It is set in a fantasy world, but I’m going to have to use real-world analogies to give you the impression of it. I may well mess up horribly, for which I apologise in advance.

Well, here is a discovery. The Empress of Salt and Fortune is a novella by Nghi Vo. It is set in a fantasy world, but I’m going to have to use real-world analogies to give you the impression of it. I may well mess up horribly, for which I apologise in advance. Wait, what? A Worldcon report already? It hasn’t even started yet. Well no, but social media has been full of outrage already, so I wanted to look at the issues raised.

Wait, what? A Worldcon report already? It hasn’t even started yet. Well no, but social media has been full of outrage already, so I wanted to look at the issues raised. In a fantasy world, a young boy discovers that he has special powers, and that he may be destined to save his people. There are hints that he will play a vital part in world-shattering affairs. This is volume one. So far so predictable, right? Well not quite.

In a fantasy world, a young boy discovers that he has special powers, and that he may be destined to save his people. There are hints that he will play a vital part in world-shattering affairs. This is volume one. So far so predictable, right? Well not quite. One of the most unlikely power couples in SF&F has emerged from Aliette de Bodard’s Dominion of the Fallen series. He is Asmodeus, Fallen Angel, ruthless head of House Hawthorn, and known as the “stabby one” because he has never met a problem that he didn’t think couldn’t be solved by the judicious application of a sharp implement to soft flesh. And He is Thaun, dragon prince, hailing from an immigrant community of Vietnamese magical creatures living in the waters of the Siene, known as the “bookish one” because he never met a problem that he didn’t think couldn’t be solved by application of knowledge and talking things through over a nice cup of tea. Together, they fight crime.

One of the most unlikely power couples in SF&F has emerged from Aliette de Bodard’s Dominion of the Fallen series. He is Asmodeus, Fallen Angel, ruthless head of House Hawthorn, and known as the “stabby one” because he has never met a problem that he didn’t think couldn’t be solved by the judicious application of a sharp implement to soft flesh. And He is Thaun, dragon prince, hailing from an immigrant community of Vietnamese magical creatures living in the waters of the Siene, known as the “bookish one” because he never met a problem that he didn’t think couldn’t be solved by application of knowledge and talking things through over a nice cup of tea. Together, they fight crime. Some American superhero shows appear very quickly on British TV. Others suffer significant delays, or don’t get there at all. One of the prime factors affecting the appearance of a show is queer content. Batwoman, for example, took ages to get on British TV. Sky wouldn’t take it at all, and it finally ended up on E4 on a Sunday night, just before Naked Attraction, which appears to be a nude dating show. That’s because Kate Kane is a lesbian. The most actual sex I’ve seen in episodes I have watched before has been a bit of kissing in bed. Doom Patrol never made it to TV at all, for reasons which will become obvious, but it is now available on Amazon Prime and you should all watch it.

Some American superhero shows appear very quickly on British TV. Others suffer significant delays, or don’t get there at all. One of the prime factors affecting the appearance of a show is queer content. Batwoman, for example, took ages to get on British TV. Sky wouldn’t take it at all, and it finally ended up on E4 on a Sunday night, just before Naked Attraction, which appears to be a nude dating show. That’s because Kate Kane is a lesbian. The most actual sex I’ve seen in episodes I have watched before has been a bit of kissing in bed. Doom Patrol never made it to TV at all, for reasons which will become obvious, but it is now available on Amazon Prime and you should all watch it. Ted Chiang collections are rare and beautiful things. They are rare, of course, because it can take Chiang a year or more to write a single story. But what stories they are. As such, Exhalation does not disappoint.

Ted Chiang collections are rare and beautiful things. They are rare, of course, because it can take Chiang a year or more to write a single story. But what stories they are. As such, Exhalation does not disappoint.

This is the June 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the June 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Chosen Spirits

Chosen Spirits Mexican Gothic

Mexican Gothic She-Ra and the Princesses of Power – Seasons 4 & 5

She-Ra and the Princesses of Power – Seasons 4 & 5 Diversity Audit

Diversity Audit The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water

The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water FINNA

FINNA Crisis on Infinite (TV) Earths

Crisis on Infinite (TV) Earths Ormeshadow

Ormeshadow For this issue’s cover I have used the cover of Juliet McKenna’s The Swordsman’s Oath. It is the second of five books in the Tales of Einarinn series, all of which are

For this issue’s cover I have used the cover of Juliet McKenna’s The Swordsman’s Oath. It is the second of five books in the Tales of Einarinn series, all of which are

A week or two ago there was a minor spat on Twitter about cyberpunk. I forget who was involved, but as I recall one side was calling for more modern and relevant cyberpunk, while the other was saying that cyberpunk was a dead genre based on an imagined future that no one believed in any more. I would like to suggest that both sides read the new novel from Samit Basu, Chosen Spirits.

A week or two ago there was a minor spat on Twitter about cyberpunk. I forget who was involved, but as I recall one side was calling for more modern and relevant cyberpunk, while the other was saying that cyberpunk was a dead genre based on an imagined future that no one believed in any more. I would like to suggest that both sides read the new novel from Samit Basu, Chosen Spirits.  Meet Noemí Taboada: party girl, fashionista, and one of the most eligible young women in Mexico City. Her father despairs of her flightiness, and her absurd ideas about going to university. How is that supposed to get you a husband? But Noemí doesn’t care. She’s young, she’s beautiful and she’s rich. The world is at her feet.

Meet Noemí Taboada: party girl, fashionista, and one of the most eligible young women in Mexico City. Her father despairs of her flightiness, and her absurd ideas about going to university. How is that supposed to get you a husband? But Noemí doesn’t care. She’s young, she’s beautiful and she’s rich. The world is at her feet. It took me a little while to get to the end of this series. I had hugely enjoyed the first three seasons, but got stuck in the middle of season 4. More about that later, but when I saw how happy everyone was with the fifth and final season I knew I had to watch it all through. I was not disappointed.

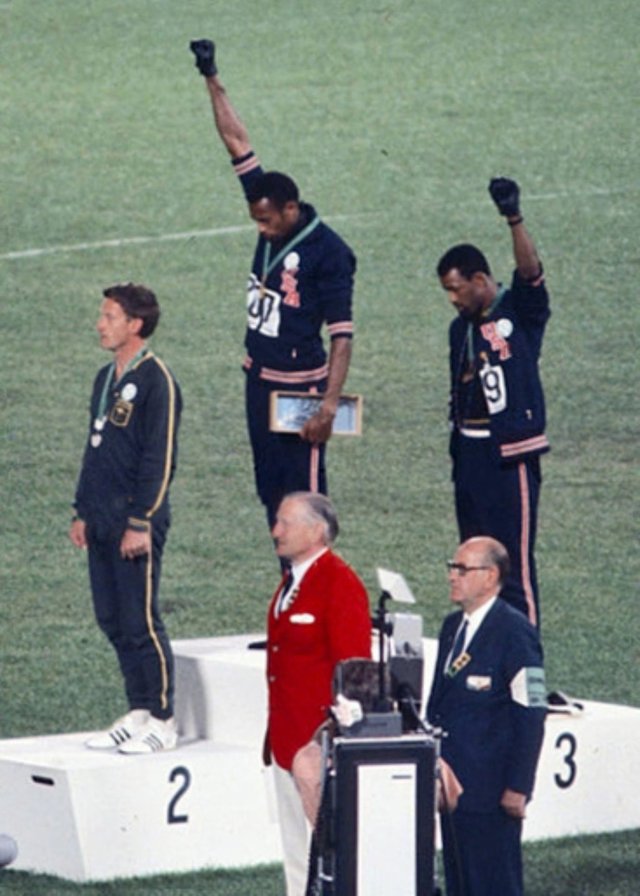

It took me a little while to get to the end of this series. I had hugely enjoyed the first three seasons, but got stuck in the middle of season 4. More about that later, but when I saw how happy everyone was with the fifth and final season I knew I had to watch it all through. I was not disappointed. In view of the new awareness of diversity issues prompted by white people finally taking the Black Lives Matter movement slightly seriously, I figured I ought to do a diversity audit of the books I have reviewed. First up, a few notes of explanation.

In view of the new awareness of diversity issues prompted by white people finally taking the Black Lives Matter movement slightly seriously, I figured I ought to do a diversity audit of the books I have reviewed. First up, a few notes of explanation. Zen Cho has described The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water as fanfic for an imaginary 50-episode wuxia TV series. I know pretty much nothing about wuxia, but if this is what it is like then I’m in.

Zen Cho has described The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water as fanfic for an imaginary 50-episode wuxia TV series. I know pretty much nothing about wuxia, but if this is what it is like then I’m in. Amy is a young woman with a stack of mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. Jules is a young, Black non-binary person doing his best to survive in an America that is clearly not welcoming to his kind. They both have shitty jobs at LitenVärld, a multi-national purveyor of Nordic kitsch and flat-pack, self-assembly furniture. Awkwardly they have just broke up after a brief and passionate affair. They have sensibly arranged to be on different shifts so that they are not in the store at the same time, but one of their co-workers, whom Amy names as Fucking Derek, has called in sick. It wouldn’t have been so bad had it not been the day that IT happened.

Amy is a young woman with a stack of mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. Jules is a young, Black non-binary person doing his best to survive in an America that is clearly not welcoming to his kind. They both have shitty jobs at LitenVärld, a multi-national purveyor of Nordic kitsch and flat-pack, self-assembly furniture. Awkwardly they have just broke up after a brief and passionate affair. They have sensibly arranged to be on different shifts so that they are not in the store at the same time, but one of their co-workers, whom Amy names as Fucking Derek, has called in sick. It wouldn’t have been so bad had it not been the day that IT happened. I have avoided crossover events in comics because they tend to require buying vast numbers of comic books that I mostly don’t have much interest in. That is, after all, the point. The comics companies hope you will like the books you don’t normally buy and stick with them. No way, comics buying is far too expensive a hobby these days.

I have avoided crossover events in comics because they tend to require buying vast numbers of comic books that I mostly don’t have much interest in. That is, after all, the point. The comics companies hope you will like the books you don’t normally buy and stick with them. No way, comics buying is far too expensive a hobby these days. I bought this book as a direct result of the

I bought this book as a direct result of the

This is the May 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the May 2020 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Network Effect

Network Effect Goldilocks

Goldilocks The Lost Future of Pepperharrow

The Lost Future of Pepperharrow Threading the Labyrinth

Threading the Labyrinth WisCon Online

WisCon Online Paper Hearts

Paper Hearts Interview – Maria Gerolemou

Interview – Maria Gerolemou The Mandalorian

The Mandalorian Earth Abides

Earth Abides Herland

Herland Oxford Fantasy Lectures

Oxford Fantasy Lectures For this issue’s cover I have made use of the common background that Ben Baldwin developed for the covers of Juliet E McKenna’s series, The Aldabreshin Compass. Juliet and I have been using these backgrounds for a series of short stories set in the same time as that series. The “Quartering the Compass” stories have been made available for free during the pandemic as part of our Lockdown Reading series. You can download them all

For this issue’s cover I have made use of the common background that Ben Baldwin developed for the covers of Juliet E McKenna’s series, The Aldabreshin Compass. Juliet and I have been using these backgrounds for a series of short stories set in the same time as that series. The “Quartering the Compass” stories have been made available for free during the pandemic as part of our Lockdown Reading series. You can download them all  I don’t think that anyone can contest the fact that Martha Wells as hit on a very successful formula with her Murderbot Diaries. She’s won two Hugos and a Nebula with the novellas, and might have won more had not there of the novellas come out in the same year. All got enough nominations to be on the final ballot, but Wells elected to withdraw two of them. Now we have a novel. It is a hot favourite for next year’s Hugos? Undoubtedly.

I don’t think that anyone can contest the fact that Martha Wells as hit on a very successful formula with her Murderbot Diaries. She’s won two Hugos and a Nebula with the novellas, and might have won more had not there of the novellas come out in the same year. All got enough nominations to be on the final ballot, but Wells elected to withdraw two of them. Now we have a novel. It is a hot favourite for next year’s Hugos? Undoubtedly.

I guess the first thing I should say about this book is that you should pay no attention to the daft quote from Publishers Weakly that you can find on the back cover. In no way is Goldilocks space opera. It is near future hard SF with a feminist edge. In the Acknowledgements section, Laura Lam has a long list of scientists whom she consulted with the get the details right. The result is the sort of book that Kim Stanley Robinson would be praised to the skies for writing. As it is written by a woman, and published in the UK by a mainstream imprint during a global pandemic, I worry about its chances. Hopefully this review will help it reach a wider audience.

I guess the first thing I should say about this book is that you should pay no attention to the daft quote from Publishers Weakly that you can find on the back cover. In no way is Goldilocks space opera. It is near future hard SF with a feminist edge. In the Acknowledgements section, Laura Lam has a long list of scientists whom she consulted with the get the details right. The result is the sort of book that Kim Stanley Robinson would be praised to the skies for writing. As it is written by a woman, and published in the UK by a mainstream imprint during a global pandemic, I worry about its chances. Hopefully this review will help it reach a wider audience.

When we left our heroes at the end of The Watchmaker of Filigree Street, Nathaniel Steepleton had settled into domestic bliss with the aforementioned watchmaker, Keita Mori, their adopted daughter, Six, and Katsu, the blue clockwork octopus. Grace Carrow had headed off to Japan with Baron Matsumoto with romance in the air.

When we left our heroes at the end of The Watchmaker of Filigree Street, Nathaniel Steepleton had settled into domestic bliss with the aforementioned watchmaker, Keita Mori, their adopted daughter, Six, and Katsu, the blue clockwork octopus. Grace Carrow had headed off to Japan with Baron Matsumoto with romance in the air.

Fond as I am of Tiffani Angus, I have to admit that her debut novel, Threading the Labyrinth, was pretty much crafted not to appeal to me. It is about gardens, and spends a fair amount of time in the 18th and 19th Centuries. It is therefore to Angus’s credit that she kept me reading all the way through.

Fond as I am of Tiffani Angus, I have to admit that her debut novel, Threading the Labyrinth, was pretty much crafted not to appeal to me. It is about gardens, and spends a fair amount of time in the 18th and 19th Centuries. It is therefore to Angus’s credit that she kept me reading all the way through.

If you had to pick a convention to put online, WisCon would probably be one of the last you would think of. Or rather it would be if you had attended a few. That’s because it is an event that is as much about community as anything else. The people who go to WisCon tend to go every year, and to book up for next year immediately the current year’s convention has finished. Despite the convention’s intersectional feminist leanings, it can be a bit insular at times, simply because it is so focused on the people who are regulars.

If you had to pick a convention to put online, WisCon would probably be one of the last you would think of. Or rather it would be if you had attended a few. That’s because it is an event that is as much about community as anything else. The people who go to WisCon tend to go every year, and to book up for next year immediately the current year’s convention has finished. Despite the convention’s intersectional feminist leanings, it can be a bit insular at times, simply because it is so focused on the people who are regulars. Anything new from Justina Robson is going to cause me to prick up my ears in interest. I’m still waiting patiently for a sequel to Glorious Angels, but wishing for books can’t make them real so I am contenting myself with Paper Hearts instead.

Anything new from Justina Robson is going to cause me to prick up my ears in interest. I’m still waiting patiently for a sequel to Glorious Angels, but wishing for books can’t make them real so I am contenting myself with Paper Hearts instead.

Those of you who have seen my talks on the prehistory of robotics will know that I have a fascination with automata in the ancient world. Now I appear to have found a soul mate. Dr. Maria Gerolemou is a Classicist currently based at the University of Exeter who shares my fascination with techne, as the Greeks called it. Recently I got to interview her. A shorter version appeared on my radio show, but this is the full thing.

Those of you who have seen my talks on the prehistory of robotics will know that I have a fascination with automata in the ancient world. Now I appear to have found a soul mate. Dr. Maria Gerolemou is a Classicist currently based at the University of Exeter who shares my fascination with techne, as the Greeks called it. Recently I got to interview her. A shorter version appeared on my radio show, but this is the full thing. Well, that was a thing.

Well, that was a thing. There’s a lot of interest in global pandemic stories these days, for obvious reasons. Over at the LA Review of Books, my friend Rob Latham has

There’s a lot of interest in global pandemic stories these days, for obvious reasons. Over at the LA Review of Books, my friend Rob Latham has

We hear a lot these days about books and authors being “of their time”, and of the Suck Fairy visiting beloved classics. Normally this is in connection with some old-time white male author who says something terrible in one of his books, but what about feminist classics? When a feminist book club I know of decided to read Herland I thought I had better find out how well it stands up these days.

We hear a lot these days about books and authors being “of their time”, and of the Suck Fairy visiting beloved classics. Normally this is in connection with some old-time white male author who says something terrible in one of his books, but what about feminist classics? When a feminist book club I know of decided to read Herland I thought I had better find out how well it stands up these days.

Thanks to following Professor Carolyne Larrington on Twitter I chanced upon the fact that Oxford University has a whole bunch of interesting lectures on the subject of fantasy literature that they ave made available for free online. Carolyne, of course, talks about A Game of Thrones, but there’s also a bunch of short introductions to other writers, plus some interesting longer pieces. There’s a great interview with my friend, Cathy Butler. There’s Margaret Kean on Phillip Pullman, and several other pieces, some of which involve Dimitra Fimi. One of the most interesting is Maria Cecire from Bard College giving a Black American woman’s view on the very English topic of rivalry between Oxford and Cambridge literary departments.

Thanks to following Professor Carolyne Larrington on Twitter I chanced upon the fact that Oxford University has a whole bunch of interesting lectures on the subject of fantasy literature that they ave made available for free online. Carolyne, of course, talks about A Game of Thrones, but there’s also a bunch of short introductions to other writers, plus some interesting longer pieces. There’s a great interview with my friend, Cathy Butler. There’s Margaret Kean on Phillip Pullman, and several other pieces, some of which involve Dimitra Fimi. One of the most interesting is Maria Cecire from Bard College giving a Black American woman’s view on the very English topic of rivalry between Oxford and Cambridge literary departments.