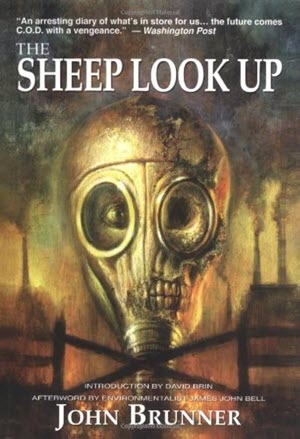

The Sheep Look Up

This review was first published in Emerald City #96, dated August 2003. Twenty-one years later, we are now scarily much closer to the world that Brunner described in his novel.

This review was first published in Emerald City #96, dated August 2003. Twenty-one years later, we are now scarily much closer to the world that Brunner described in his novel.

Science fiction books are not generally supposed to be predictive. Where they do include things like social and political commentary, their writers intend them to be read as an examination of how we live today, not some irrelevant tale about the future. Even so, some SF writers do manage to sound awfully prescient after the event. This is particularly true if they concentrate on near-future stories. John Brunner (The Shockwave Rider) and Pat Cadigan (Synners) are now credited with having foreseen computer viruses and spam. Philip K. Dick’s work is currently hugely popular as a reflection of modern society, though people thought him paranoid when he wrote his books. But perhaps the most prescient SF book ever written is also one of the least known, at least outside the environmentalist movement. Now at last it has been reissued by a small press company in the US. In 1972 when it was released, John Brunner’s The Sheep Look Up seemed an unlikely nightmare vision of the future. These days it is scarily prophetic. The quotes from The Independent and New Scientist are real.

I am especially pleased to see […] The Sheep Look Up reappear in a fine edition. Its warning, and stark, terrifying beauty, are just as relevant today, even if its message has been partly heeded. For we need reminders that the ultimate decision is ours.

David Brin

from his Introduction to the new edition

At its most basic, The Sheep Look Up is an eco-disaster novel, much like Oryx and Crake. However, there is no mad scientist plotting the downfall of the human race. It is a book entirely about incompetence, greed, and the remarkable fragility of our modern world when faced with disaster. Brunner did not consider the possible collapse of power grids — his agenda was purely in the area of biosciences — but his awareness of the type of trouble we could get ourselves into was striking.

More cows had died in the night, bellies bloated, blood leaking from their mouths and nostrils, frozen smears of blood under their tails. Before the children were allowed to go to school they had to dip their rubber boots in pans of milky disinfectant. The same had been sprayed on the tires of the bus.

The book has an innovative structure, being made up of a monthly diary of seemingly unconnected events that eventually coalesce to form a coherent plot. Many of the entries under a particular month are quite short: a news report or extract from a political speech. Others follow the declining fortunes of a range of well-meaning but largely ignorant characters as their world falls apart around them.

The story begins with an horrific outbreak of violence in a small African state caused by a shipment of food aid that turns out to have been contaminated with an ergot-like hallucinogen. The Africans, used to a long history of American economic imperialism (if you don’t think that happens see the quote below, and yes I suspect the EU is just as bad), assume that they are being deliberately poisoned.

US cotton subsidies […] Oxfam claims, are distorting the world market with payments worth $4bn a year — more than America spends on aid for the whole of Africa — enabling America’s 25,000 cotton farmers to dump their produce on the international market and get rich in the process. World cotton prices are now lower than at any time since the 1930s Depression, causing an economic and social crisis in sub-Saharan Africa and tipping the 10 million people who depend on cotton for their livelihood below the poverty line.

The Independent Magazine

16 August 2003

The tale of how the contaminant got into the food, and the impact this has on US society, forms the backbone of the novel. Along the way, the US President, a character portrayed as a bumbling idiot who speaks in tabloid newspaper headlines, claims that terrorists have attacked the US with biological and chemical weapons. A war on terrorism is declared and draconian security measures are instituted.

Meanwhile, in the US, public health is becoming a major issue. More and more children are being born with diseases such as asthma, and even physical deformities. Tap water is unsafe to drink. Medicines cease working, as bacteria become resistant to antibiotics. The cost of health insurance skyrockets. Does any of this sound familiar?

“You bastard,” she said. “You smug pompous devil. You liar. You filthy dishonest old man. You put the poison in the world, you and your generation. You crippled my children. You made sure they’d never eat clean food, drink pure water, breathe sweet air. And when someone comes to you for help you turn your back.”

Thankfully much of what Brunner foresaw has not come to pass. The Sheep Look Up was significantly instrumental in the founding of the environmental movement (Brunner himself was one of the founders of CND). As a result, DDT is no longer commonly used as a pesticide (at least not in countries with firm environmental regulations), supersonic planes do not over-fly the US causing avalanches in the Rockies and the Mediterranean is not a fetid cesspool. Of course as a result we also have extremists like the Animal Liberation Front to deal with. But Brunner foresaw that too. In the novel his environmentalist hero, Austin Train, despairs at the violence done in his name.

Even this far from shore, the night stank. The sea moved lazily, its embryo waves aborted before cresting the layer of oily residues surrounding the hull, impermeable as sheet plastic: a mixture of detergents, sewage, industrial chemicals, and the microscopic cellulose fibers due to toilet paper and newsprint. There was no sound of fish breaking the surface. There were no fish.

There are also elements of The Sheep Look Up that will jar with a modern readership. Although Brunner demonstrates a social conscience throughout, characters in the book express attitudes regarding race, gender and sexual preference that are likely to be the cause of a discrimination suit if uttered in public in a Western society today. But of course Brunner is only commenting on society as it was in his day, like any good SF writer should.

“What frightens me in retrospect about The Sheep Look Up […] is that I invented literally nothing for it, bar a chemical weapon that made people psychotic. Everything else I took straight out of the papers.”

John Brunner

You won’t find any comfort in reading The Sheep Look Up. Brunner is unrelentingly bleak in his prose. Although his “sheep” do finally decide that the way their world is going is not what they want, and that they must take action, it is far too late for them. Possibly the planet can be saved, but for individuals there is no hope. There are books (including Oryx and Crake) in which the author destroys the world in some spectacular cataclysm or disaster. But The Sheep Look Up is the only novel I can think of in which almost every character you meet dies alone, unheroically, and often through some stupid accident or mistake. But that, as David Brin says, is the terrible beauty of the book. It is a stark and uncompromising warning of what can happen to a world that puts short-term comfort and political expediency before all else. Just as in 1972, we can read it and think, “it couldn’t happen to us.” But in the intervening years much of it has. And it could yet get worse.

The growing trend around the world to drink water from underground sources is causing a global epidemic of arsenic poisoning. Tens of thousands of people have developed skin lesions, cancers and other symptoms, and many have died. Hundreds of millions are now thought to be at serious risk.

New Scientist

9 August 2003

Title: The Sheep Look Up

By: John Brunner

Publisher: Benbella

Purchase links:

Amazon UK

Amazon US

See here for information about buying books though Salon Futura