Believing in Snow

Cheryl Morgan ponders different barriers to suspension of disbelief.

When I first started planning a column for this issue the idea I had in my head was to read a number of books that involved snow in some way. It is, after all, that time of year, at least in the hemisphere where I live, so it seemed appropriate. The more I read, however, the more I found that my chosen books were connected by something much more interesting: the process of suspension of disbelief.

As you are probably aware, suspension of disbelief is a theory of one of the ways in which fiction works that was first suggested by Coleridge and was famously challenged and expanded upon by Tolkien in his essay, “On Fairy-Stories”. The basic idea is that, in order for the reader (or viewer/listener/participant) to engage successfully with the story, she has to be able to accept that what is happening in it is somehow “real”. Exactly how that works, and indeed whether it is necessary in all cases, is open to debate, but it is also true that what works for one reader cannot be guaranteed to work for another. That’s true both on a personal level, and on the more generic level of the type of fiction you read. These books illustrate the point rather nicely.

I started out with Karin Lowachee’s Gaslight Dogs [Purchase] because I knew that Karin had based one of the cultures in the book on the Inuit people, amongst whom she lived for a while (see Karin’s guest appearance in The Salon for more details). As it turns out, only the first chapter or so is actually set in the far north, so there is almost no snow in the book, but I read it anyway and am glad that I did.

There are two facets of Lowachee’s book that are liable to immediately mark it out as “fantasy”, and therefore unreadable to large numbers of people because it is “not real”. Of course the book is actually very much about the real world. It is about colonialism, and about how colonial powers ruthlessly exploit conquered peoples in pursuit of their own aims. Lowachee has chosen not to write about the real North America, and has chosen to give the native people of her parallel version of that continent actual magic powers. The former choice is simply a matter of filing off the serial numbers so as to have a familiar yet blank canvass on which to work. The latter accentuates the drama and gives the fantasy reader something interesting to learn about as the story progresses.

Both of these things are liable to cause the reader of realist fiction problems, but they are meat and drink to the average speculative fiction reader. No one reading Salon Futura is likely to turn a hair at being asked to believe in this alternate North America, nor that some of the native people can summon animal spirits. But as I read the book I realized that there was something about it that could cause a speculative fiction fan to balk.

The book has two main characters: Sjennonirk, the native wolf-girl whose picture adorns the cover, and Captain Jarrett Fawle, the colonial army officer who is given the task of learning about her strange powers. If this were a traditional science fiction book, Fawle would be all over this fascinating new thing and investigating it scientifically. But that’s not the book that Lowachee is writing. Instead Fawle refuses to believe the evidence of his own eyes. The more he finds out about Sjenn’s powers, the more hysterically he tries to deny them. His reasons for this are good, and will become clear to anyone reading the book. However, that sort of character is a much more challenging task for a writer to carry off, especially when her readers are the sort of people who are conditioned to believe. I’m not quite convinced that Lowachee has made Fawle’s madness work, and even if she has, some readers may still be unable to accept it, conditioned as they are to expect heroes who are Competent Men. But Gaslight Dogs is nonetheless an ambitious book that becomes more interesting as the story develops.

Still in search of snow, I headed off to Antarctica, by way of Ian Culbard’s graphic novel adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s The Mountains of Madness [Purchase]. This was one of the books that was warmly recommended by all in last month’s Salon podcast. It is a fascinating outside pick for a Hugo nomination this year, especially as the idea of giving dear old HPL a Hugo is bound to appeal to fandom’s sense of whimsy.

There was, of course, no shortage of snow, but was there belief? You see, for all his ingenuity in creating a whole mythology based on vast, unknowable and uncaring tentacled monstrosities, Lovecraft suffered from a fundamental problem for a writer: he was very much out of touch with the rest of humanity. Many of the things that Lovecraft writes about are genuinely horrifying. Others, or sometimes simply his overwrought descriptions, leave most readers sniggering rather than quivering. How does Culbard manage with this difficult material?

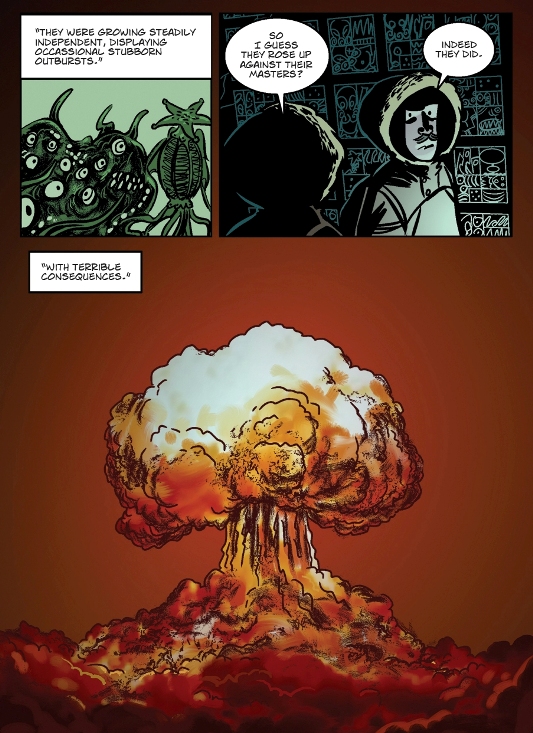

The basic look of the book is fairly simple and stylized. The colors are mostly drab, as befits an air of menace, with some nice use of red in one of the few genuinely horrific scenes in the story. The characters look right for the period, and a bit Tintin-like, which suits an expedition into the unknown. There is also some very nice pacing. The following page, also chosen by Richard Bruton to illustrate his review of the book for Joe Gordon’s FPI blog, demonstrates both the power of Culbard’s adaptation and the problems it faces.

The use of an image of a mushroom cloud to represent the war between the Old Ones and the Shoggoths is a brilliant piece of shorthand. Obviously it is not in the original. Atom bombs hadn’t been invented when Lovecraft wrote the story. But to the modern reader it is an image that instantly coveys the idea of an hideously destructive conflict. Also it cleverly suggests that the technology that the Old Ones possessed was well beyond that of Professor Dyer and his colleagues.

Unfortunately, as you can see, drawing a convincingly horrible picture of a Shoggoth was something Culbard didn’t manage to pull off. And then there is one of those Lovecraft moments that leaves everyone shaking their heads in despair: the encounter with the giant killer penguins. Lovecraft hated the cold, so perhaps penguins did indeed scare him. For most of us, however, especially those of us who grew up watching Burgess Meredith menace Batman, penguins, even giant ones, are figures of fun. You almost feel that this section of the story needs to be an out-take introduced by someone saying, “and now for something completely different…”

Overall I really like Culbard’s adaptation, which conveys the story concisely and elegantly, but I also concur with Bruton that it isn’t very scary. That is more Lovecraft’s fault that Culbard’s. It remains to be seen what Guillermo del Toro can do with this bizarre mish-mash of a story1.

There is plenty of snow too in Graham Joyce’s latest novel: The Silent Land [Purchase]. Indeed, there is rather too much snow for the central characters, Zoe and Jake, who are caught in an avalanche in chapter one and barely escape with their lives. Or do they? Because when they finally make it back to their hotel they can’t find anyone else alive. Nor can they get the TV or their phones to work. Slowly it dawns on them that they might actually be dead after all.

The interesting thing about this book, at least as far as the theme of this article goes, is that it is by no means clear what we are being expected to believe. If you view the story through a fantasy lens then you will expect there to be a convincingly fantastical explanation for what has befallen Zoe and Jake. You will have a particular ending in mind that may involve an encounter with some sort of mythological being. Alternatively, if you view the story through a science fictional lens you might expect to discover that our heroes are trapped in some sort of virtual reality system such as that in Tad Williams’ Otherland books. Then again, you could view the book through a religious lens and be looking forward to some sort of faith-affirming message at the end.

The beauty of this book is that, as with Schrödinger’s cat, until we open the box of the final chapter, we have no idea whether Zoe and Jake are alive or dead. Any one of those explanations is plausible, and there could be others that I haven’t suggested. Trying to guess where Joyce is going is part of the fun of reading the book. The problem, however, is that each of these possible endings plays to a particular set of expectations, and most readers won’t be able to handle more than one or two of them without their heads exploding. If, for example, you were expecting a purely naturalistic explanation for the story, and our characters find themselves face-to-face with an ancient Pyrenean mountain god, you are not going to be happy. One person I follow on Twitter was positively volcanic with fury when he got to the end, though I have no idea what he was expecting. It is a brave and clever thing that Joyce has done with this book, but it may lose him a few friends.

There is also one final twist. I hope I’m not giving too much away by saying that one’s belief in the ending is dependent on accepting that Zoe and Jake are desperately in love. Well, you could have fooled me! I know that there are couples who love each other very much yet bicker constantly. That sort of relationship has never appealed to me. I know that this is a personal reaction on my part, but nevertheless it meant that the book didn’t work for me.

My final book this month is also set in a famously snowy wasteland: Siberia. Marcel Theroux’s Far North [Purchase] is a post-apocalyptic tale that was short-listed for the Arthur C. Clarke Award last year. The Clarke has something of a reputation for always picking one book written by someone from outside the science fiction community. The first ever winner was Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Personally I rather like this, but the whys and wherefores of such a policy, if indeed the policy they even exist, are not relevant here. The point is that for 2010 Far North was that book.

There is no doubt that Far North is, in a way, science fiction. It is, after all, set in the future. But for most of the book we are asked very little in the way of suspension of disbelief. All we have to take on board is that human civilization has collapsed thanks to the effects of climate change, over population, resource wars, and the inevitable stupidity and greed of politicians. Is that so hard to believe?

The action takes place in Siberia because, in Theroux’s future history, a group of religious idealists (Quakers rather than fundamentalists) decide to leave the USA and buy land in the far north of Russia where they can live simple, peaceful lives as God intended. This again is hardly a huge stretch of the imagination. Nor is the fact that when war, famine and disease engulfs the rest of the planet, these idealistic religious communes fare very badly thanks to an influx of starving, non-American, often non-Christian refugees. The book is in many ways a cousin to Lord of the Flies. This little exchange says it all.

I told him that from what I had observed, it only took three days before desperation and hunger overturned all civilized instinct in a person. He smiled and said I had a bleak view of human nature, and that in his experience, it was nearer to four days.

Towards the end of the book we do encounter a small amount of futuristic technology. However, it is not central to the book in any way other than that it exists. One item provides nostalgia for the world that was lost, by allowing the characters to see a recording of life from before the fall; the other is simply mysterious, and by implication both powerful and valuable.

As I hope you can see, Theroux makes very few demands on his readers in terms of suspension of disbelief, and what he does ask of us is the sort of extrapolation that just about everyone can manage. We can all envisage exactly this sort of disaster happening. You can almost imagine Theroux standing up and proclaiming, “My book is entirely believable extrapolation of current political trends. It doesn’t contain any science-fictional nonsense about genetic engineering like Ms. Atwood’s Oryx and Crake.” You can easily see why Faber and Faber had no qualms about marketing this book to a general audience. And yet it is set in the future, in a society that doesn’t exist and probably never will. It even does the classic science fiction thing of using an invented world to allow the author to ask questions about the nature of the human condition and our place in the world. One day I expect to see academic papers citing it as a classic example of the Mundane SF movement.

I should add that Far North was my favorite of the four books I read this month. I thought the plot was a bit contrived in places, but the elegance and power of Thoreaux’s prose made up for that and the ending was very cunningly worked out. But the failure modes of the other books are interesting. I was perfectly happy to believe in a girl with a wolf spirit, an alien city in the wastes of Antarctica, and the various explanations that Joyce holds out for obtaining life after death. The things I tripped up on were a character descending into madness, the scariness of giant penguins, and a not very caring love affair. Any of those could equally be a problem with a book that has no fantastical elements at all.

1. Gary K. Wolfe discusses Del Toro’s project on the latest Notes from Coode Street podcast, including mention of this New Yorker interview. Most relevant to this article is that Gary says reading Lovecraft requires a special skill: not suspension of disbelief, but suspension of grammatical taste.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting Salon Futura financially, either by buying from the Wizard's Tower Bookstore, or by donating money directly via PayPal.