Mediaeval Women

Those of you who follow me on BlueSky will remember me posting about my visit to the Mediaeval Women exhibition at the British Library. As social media is rather ephemeral, I will recap some of what I said here, but mainly this is a review of the book of the exhibition.

Those of you who follow me on BlueSky will remember me posting about my visit to the Mediaeval Women exhibition at the British Library. As social media is rather ephemeral, I will recap some of what I said here, but mainly this is a review of the book of the exhibition.

While seeing an exhibition in person is wonderful because of the personal connection you can have to the items on display, I often find the book to be of equal or greater value. You are not pressed for time when reading it, not surrounded by crowds. Also the curators have much more space in which to expound their themes. That is particularly valuable in the case of any exhibition where there may be political constraints on what can be said on the exhibit labels.

My main complaint about the exhibition is that it foregrounded a very “traditional” view of women and played down they amazing things that the women of that period could and did achieve. At first glance the book follows the same pattern. It begins with a section on ‘Private Lives’ in which women are kept firmly in their roles of daughter, wife and mother. We then go through ‘Public Lives’ and ‘Working Lives’ to ‘Spiritual Lives’ where women are once more sequestered away, this time in the cloister.

However, once you dive into the book, you get a much more nuanced view. The ‘Private Lives’ section spends a good deal of space talking about women’s role in medicine. ‘Public Lives’ opens with an admission that this section is mainly about women who achieved political power. And the ‘Spiritual Lives’ section does make it clear that entering a nunnery was a way in which women could achieve wealth and power (and pet cats) with very little interference from men, and freedom from the expectation to breed.

As a consequence, the book is far better in its coverage of Empress Matilda, who was most shamefully disparaged by the exhibition label. She was Empress of the Romans by dint of her marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor, and Queen of England by order of her father, Henry I. None of this was invention or self-aggrandisement on her part.

The book (and exhibition) concentrates primarily on Europe because the term ‘mediaeval’ has little meaning outside of that context. But there was significant contact between the Christian and Muslim worlds, and one European country – Spain – was in large part Muslim ruled. As a result we do have a few Muslim women in the book, perhaps most excitingly the amazing story of Shajar al-Durr who rose from being a slave concubine to be, for a few glorious months, Sultan of Egypt and Syria. She held her country together when her husband died fighting the Crusaders, and seems to have relinquished power to one of her generals only because of the impracticality of ruling from the confines of the women’s quarters. She continued to play a major role in Egyptian politics for years afterwards.

The full title of the book is Mediaeval Women: Voices and Visions. That’s partly because we do sometimes have their words, as opposed to words written by male contemporaries, and partly because women sometimes played a major role in the book trade. One of the stars of the book is the feminist writer, Christine de Pizan who, along with Isabella of France and Joan of Arc, is a major inspiration for Guy Kay’s Written on the Dark. Also featured is Jeanne de Montbaston, the creator of the hilarious ‘penis tree’ image.

The book is edited by Eleanor Jackson and Julian Harrison, primarily because of their jobs at the British Library looking after its collection of mediaeval manuscripts. While having a male co-editor does not perhaps give the right impression, the majority of the contributors are women. Also two of them openly identify as non-binary, including Rowan Wilson who penned the excellent and very respectful section on the transfeminine sex worker, Eleanor Rykener.

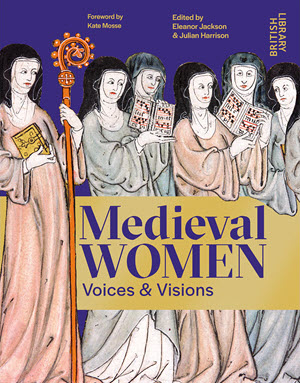

Although the exhibition is now closed, the book is still available from the British Library shop and from Amazon. At around £25 for a hardcover it is exceptional value. It is a hefty tome with high quality paper and is absolutely stuffed full of colour illustrations that are mainly taken from stunning illuminated manuscripts. Yes, it is a coffee table book, but it is also informative and has an excellent section on suggested further reading for those of us who want to know more about the women it features.

Title: Mediaeval Women: Voices and Visions

By: Eleanor Jackson (ed.) & Julian Harrison (ed.)

Publisher: The British Library

Purchase links:

Amazon UK

Amazon US

See here for information about buying books though Salon Futura