The Association of Welsh Writing in English Conference

One of the interesting things about conquests and colonization is how language shifts as a result. England was conquered by the Normans in 1066. The Norman aristocracy continued to speak French for a long time thereafter, but the English people never adopted that language and eventually the nobility started speaking English. It took the Normans a lot longer to extend their conquest into Wales, and it wasn’t really until the time of Henry VIII that Wales became fully subsumed into the British state. People in Wales continued to speak Welsh right up until the 19th Century, when the Victorians decided that the Welsh should be forced to speak English, on pain of strict punishment. Since Devolution, the Welsh language has seen something of a revival, at least in official spheres, but the rise of English as a world language has made it hard to explain to young Welsh people why they should have to learn their native tongue.

One of the interesting things about conquests and colonization is how language shifts as a result. England was conquered by the Normans in 1066. The Norman aristocracy continued to speak French for a long time thereafter, but the English people never adopted that language and eventually the nobility started speaking English. It took the Normans a lot longer to extend their conquest into Wales, and it wasn’t really until the time of Henry VIII that Wales became fully subsumed into the British state. People in Wales continued to speak Welsh right up until the 19th Century, when the Victorians decided that the Welsh should be forced to speak English, on pain of strict punishment. Since Devolution, the Welsh language has seen something of a revival, at least in official spheres, but the rise of English as a world language has made it hard to explain to young Welsh people why they should have to learn their native tongue.

What does all this mean for Welsh Literature? There are some who think that to count as such a work has to be written in Welsh. But if you insist on that strict definition you are ruling out, amongst much else, the entire oeuvre of Dylan Thomas, arguably the greatest Welsh poet ever. Not to mention the great Welsh fantasy and horror writer, Arthur Machen. So most people accept that Welsh literature can be written in English. They still argue over whether the author has to have been born in Wales, live in Wales, be eligible to play rugby for Wales, or any other definition of nationality, but Welsh Literature written in English is officially a thing. And that means that academics will study it.

So, an academic conference, at a lovely location in central Wales, and an opportunity to give a paper about Nicola’s Griffith’s brilliant novel, Spear. How could I resist?

Let’s start with the venue. Gregynog Hall is a mock-Tudor stately home situated in large grounds a few miles north of the town of Newtown in Powys. While the area has been occupied since at least the 12th century, the current building is only around 150 years old. The ‘half-timbered’ look is entirely artificial. Of rather more interest is that the whole thing was done using what, for the 19th century, was a new and unusual building material—concrete.

Prior to the reconstruction, there was a Jacobean mansion on the site. The builders left one room of that house standing, and built the new house around it. The so-called Blayney Room dates from 1636 and is entirely wood-paneled, with all sorts of interesting carvings that I would love to investigate more.

The Hall has extensive gardens (including several Redwood trees which just love the damp Welsh climate). I’m told that we got a superb view of the aurora on the Friday night. Sadly I had gone to bed and missed the whole thing.

One downside of the venue is that it is not very accessible. In particular the two conference rooms are on the second floor (third floor if you are American) and there is no lift. However, there is good wifi in the conference areas and the event is mostly hybrid.

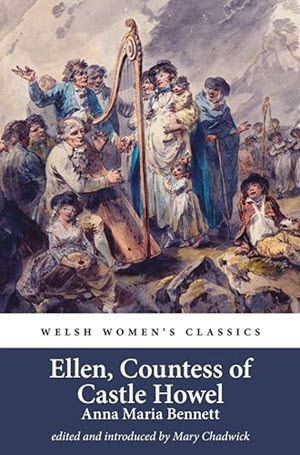

This being Wales, much of the content was about poetry. We even had some well-known poets at the event, including the fabulous Taz Rahman. But there were things more in my wheelhouse as well. I was particularly impressed by the opening keynote from Dr. Mary Chadwick. She has just edited a new edition of Ellen, Countess of Castle Howel by Anna Maria Bennett. That’s a book you have probably never heard of, and indeed this is the first new edition since 1794, but it was a massive best-seller in its time, alongside works by Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding. Along with Bennett’s six other works, it was almost certainly read with enthusiasm by the teenage Jane Austen. There were, after all, not many women novelists for her to read.

Bennett has been forgotten for many reasons, starting with her being a woman. She was also Welsh, hailing from Merthyr Tydfil with a family name of Evans. After an unhappy marriage to a Bristol man called Thomas Bennett, she ran away to London where she caught the eye of Admiral Thomas Pye. She was his mistress for many years, and turned to writing only when the relationship began to sour. All of her books were published after Pye’s death, and the income from them helped Bennett and her daughters survive. One of those daughters, Harriet, became an actress and mistress of the Duke of Hamilton.

I do love a bit of forgotten feminist history, and this was a fine example of the genre.

There were presentations from some current creative writing students. My friend Jo Lambert is working on a story about the legendary Welsh outlaw, Twm Siôn Cati, who seems much more interesting than the modern, sanitized versions of his story make out. Also Mari Elis Dunning has a forthcoming novel called Witsch, about an alleged witch from early modern Wales. The history of witch trials in Britain is fascinating for many reasons, one of which is the geographic distribution. While the Scots condemned thousands of alleged witches to death, and the English hundreds, the Welsh executed precisely 5. Mari argues that a Welsh witch would only be found guilty if she had fallen foul of the local nobility; otherwise she was a valued member of the community.

My own paper went down well enough, though it did suffer from being in the part of the schedule that was double-streamed. I also got to meet and chat to some of the great and good of Welsh publishing, which will hopefully be useful for Wizard’s Tower. I very much enjoyed the weekend, and look forward to going again next year.