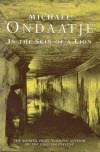

In The Skin of a Lion

Sam Jordison finds a sense of wonder in Michael Ondaatje’s In The Skin Of A Lion.

Big machines. Little people. Chunks of metal. Flesh and blood. Advanced incomprehensible technology. Simple, uncomprehending humanity.

Anyone who has spent enough time reading speculative fiction will be aware of the potential in such collisions. Just think of the awe and fear as Norton looks on the cylindrical sea of Rama. The wonder and mystery of the Ringworld. The complete and utter headmash of the Pump in The Gods Themselves. And the terror…

It’s a subject that genre writers have made their own. Or just about their own. One of my favourite variations on this endlessly renewable theme actually comes in a book called In The Skin Of A Lion by the poet turned Booker-prize-winning novelist, Michael Ondaatje [Purchase].

It’s a subject that genre writers have made their own. Or just about their own. One of my favourite variations on this endlessly renewable theme actually comes in a book called In The Skin Of A Lion by the poet turned Booker-prize-winning novelist, Michael Ondaatje [Purchase].

Ondaatje is not normally associated with ideas explored in speculative fiction. I suspect that those who haven’t read him, but might have heard of him, even think of Ondaatje as one of those flowery, chattery writers popular with women of a certain class and age. I know I used to harbour the same prejudice. For a while all I knew about him was that his book The English Patient had won the Booker, and that Anthony Minghela had made it into a film that fetishised Italian sunshine and late British colonial costumes. Luckily, my opinion began to change in my late teens when I watched the film anyway and realised that, even though my Mum liked it, it was actually bloody good. My relationship with the author has been on an upward curve ever since.

Yes, Ondaatje’s writing is at the higher end of literary fiction indulgence. It’s as rich and sensuous as sandalwood, and luxurious as a hot deep bath. But it should never be mistaken for decadent. There’s a steel fist inside the lovely velvet glove of his prose: an angry social conscience, a sensibility that is lustful as much as romantic, and a real sense of rage. There’s also a determination to experiment with form and ideas — which is where Salon Futura comes in and I get to continue the theme I took up in my earlier discussion of E.L. Doctorow’s Waterworks .

Coincidentally (or possibly not), In The Skin Of A Lion also has a giant waterworks developed by an over-powerful city official at its centre. This time, it’s the RC Harris water treatment plant in Toronto, a huge imposing structure built in the 1930s with an “entrance modelled on a Byzantine city gate”, and an interior with “tiling and terrazzo by Italian Mosaic and Tile Company…”. A treatment plant that still works today, incidentally, and that has also become popular with tourists who flock through its ornate corridors to marvel at Harris’ ostentation and vision.

In the novel, the main part of that vision focuses on the gigantic water plant as a lifeline. Harris is curiously obsessed by the notion that Rome might have fallen to the Goths had they poisoned its viaducts, and sees a constant source of clean water as the salvation of civilisation. To an extent, Ondaatje backs up this idea. Again and again water appears in the book in the role of rescuer. Characters escape danger in boats and canoes, they plunge into water to put out the fires that are about to consume them, they find peace in lake waters. When a character called Caravaggio is beaten up in prison, we are told: “He needs more than anything to get on his knees and lap up water from a saucer.”

But Ondaatje has a more complex view of water and civilisation than Harris. Focussing on the fictional Patrick Lewis, one of Harris’ hundreds of employees, he shows the human cost of such advances. Particularly, the monumental effort that goes into creating such Ozymandian structures:

“Work continues. The grunt into hard clay. The wet slap. Men burning rock and shattering it wherever they come across it. Filling hundreds of barrels with liquid mud and hauling them out of the tunnel. In the east of the city a tunnel is being built out under the lake in order to lay intake pipes for the new waterworks… Exhaustion overpowers Patrick and the other tunellers within twenty minutes, the arm itching, the chest dry. Then an hour more, then another four hours till lunch when they have thirty minutes to eat.”

It’s the scale that most impresses. Lives are thrown away to complete the work. Men are nothing against it:

“The cut of the shovel into clay is all Patrick sees in the brown slippery darkness. He feels the whole continent in front of him.”

Or, as Patrick later expresses it when he meets Harris: “Your goddam herringbones in the toilets cost more than half our salaries put together…”1

Ondaatje has the ability to absorb his readers into Patrick’s life, and absorb Patrick’s life into his readers; to make them feel as if they are looking out at the world from the inside of his skull, make them share his joys and suffer his pains. He has created a loving, complicated, fascinating man. And yet, measured up against Harris’ “temple”, Patrick might as well be nothing. All human warmth fizzles out in the dark waters of that giant machine.

This idea of the cold impersonality of technology is a strong force in the book, but also one that is open to contradictory currents. One of Harris’ earliest projects is the Prince Edward Street viaduct. The arching of all that concrete and steel over the Don Valley, and the fearsome battle with gravity it entails, is described towards the start of the book. (Not recommended reading for vertigo sufferers, but otherwise, thrilling.) One night, we are told, during the construction, a party of nuns strays onto the bridge and the wind begins to scatter them. Workers grab most of the women, but one is lifted up and:

“then the wind jerked her sideways, scraping her along the concrete and right off the edge of the bridge. She disappeared into the night by the third abutment, into the long depth of air which normally held nothing, only sometimes a rivet or a dropped hammer during the day.”

Ondaatje adds:

“…the incredible had happened. A nun had fallen off the Prince Edward Viaduct before it was even finished… Commissioner Harris at the far end stared along the mad pathway. This was his first child and it had already become a murderer.”

But the twists don’t end there. We soon learn the bridge didn’t kill anyone. It actually gives someone a new life. As the nun is falling she is grabbed by Nicholas Temelcoff, a worker on the bridge. The only damage done is that her weight wrenches his arm from its socket. She helps him fix the dislocated shoulder, removes her veil and uses it to wrap it tight, goes back to his house, drinks brandy, cuts her hair… and moves into the world of love. Eventually, she finds Patrick — and so it is that Harris’ creations give Patrick’s life meaning as much as they drain it of significance.

At this stage, I should pause. This many-sided exploration of man and technology is so good that I’ve let it take up almost all of this article, but really it’s just a small part of In The Skin Of A Lion. Ondaatje submits plenty of other gnarly subjects to similar scrutiny. There are involving explorations of social justice, how good men can turn to violence, how to define crime… It’s full of thick and meaty brain food, as is proved by its regular appearance on exam papers in its native Canada.

Yet already, I must pause again. I don’t want you to think of this book as some worthy, dead, set-text. Provoking as all those big ideas are, they aren’t the only reason I find myself returning to In The Skin Of A Lion again and again. Nor are they the reason I’m so eager to press it on you.

The other big thing about this novel is the fact that it’s tremendous fun. It’s a rollicking love story, rich and full-bodied (in many senses). It’s a bright collage of beautiful images. It’s also — in common with many books that take on the subject of man versus machinery — imbued with the joy of blowing shit up. Also, the horror. Also the pain of the aftermath. Also, the tension that builds before the explosion.

There are fantastic descriptions of loggers blowing up trees in the Canadian wilderness (a “twenty foot log suddenly leaping out of the water…”), of hotels being blown apart, of bombs and of Molotov cocktails. In the final chapter Patrick takes his argument against technology and the men who control it to its logical extreme and he launches an attack the waterworks, dynamite strapped to his body, swimming in through an underwater tunnel. It’s a masterpiece of incrementally mounting pressure – and also of sudden release.

It doesn’t diffuse the drama to say that Patrick fails in his attempt. Nor does it give the game away. It’s how he fails that matters. Besides, to come back to the main theme, we know that Harris’ waterworks are still standing. That they are still, indeed, a source of marvel. That tourists still flock to see those great Babylonian gates and the tiles that cost more than all those men’s wages. And so in reality, as in the novel, a tricky argument remains resolved. Is a structure that brings pleasure and practical benefit to thousands of people for hundreds of years worth more than an individual life? More than the hundreds of lives made miserable to build it? And does technological innovation rule the men or men rule technology? Ondaatje certainly doesn’t give us answers. But he does give us new ways of thinking about the questions — and for that and so much else In The Skin Of A Lion is essential reading.

1. The herringbones referred to are patterns in decorative tiles.