SF and IR

Ken MacLeod finds interest in science fiction in a place you may not expect it.

If you’d been in the New Academic Building of the London School of Economics on Thursday 17 February 2011, you’d have heard a lot about SF and IR.

You know what SF is, but what’s IR?

IR is International Relations, the academic discipline that studies and theorises about the relations between states — usually from the point of view of the currently powerful states. SF, with its wars of the worlds, its starship troopers, its Empires, Federations and Cultures, its alternative histories, its utopias and dystopias, colonial revolts and alien races, has projected these relations onto a big screen. Sometimes SF has critically reflected on these relations. Other times, it has merely reflected them. Either way, the result has provided plenty of raw text for IR theorists to interrogate, and — rather below the radar of the SF community itself — they have [To Seek Out New Worlds: Exploring Links Between Science Fiction and World Politics by Jutta Weldes Purchase].

As part of this year’s Space for Thought Literary Festival, which was on the theme of “Crossing Borders”, the LSE’s Department of International Relations ran two events on “Science Fiction and International Orders”: a panel and a roundtable. They invited three SF writers: me, Paul McAuley, and Jon Courtenay Grimwood, to take part, along with three IR academics: Americans Dan Nexon and Patrick Jackson, and Norwegian Iver Neumann — all of whom have written about SF/F and IR. The relevance of Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica may seem obvious, that of Harry Potter [Harry Potter and International Relations, edited by Daniel Nexon and Iver B. Neumann Purchase] less so, but they’ve all been dilithium for their academic engines.

The events attracted a sizeable audience for a Thursday afternoon, with over a hundred people for the panel and perhaps half that number for the roundtable, and were regarded by all involved as a great success. They were live-blogged by Stephanie Carvin, who teaches IR at Royal Holloway and who is (if her blog title‘s anything to go by) clearly a Young Hegelian.

The panel, chaired by c.*******@ls*.uk“>Professor Chris Brown, featured talks and readings from the SF writers, with comments and questions from academics and the audience; the second, chaired by b.*******@ls*.uk“>Professor Barry Buzan, featured the academics making presentations, and comments and questions from the audience and the SF writers. And then, in the grand common tradition of SF and academia, we all went to the pub, and on for dinner — where, also in these traditions, the conversation continued, fast and loud.

Jon read from his latest novel, The Fallen Blade [Purchase], the opening volume of a trilogy for which the elevator pitch is “vampires in Venice” — an alternate Renaissance Venice, that is. As in his earlier series, Jon eschews the simplistic one-slip historical points-shift to set his alternate history on track. A complex concatenation of events — a Chinese fleet that didn’t sink, a key part played by Marco Polo in the conquest of Japan — results in a fifteenth century where China and the Caliphate are superpowers and Marco Polo’s family rule Venice. God knows where the vampires come from. Sitting beside Jon, I was intrigued to see that he was reading from a proof copy, whose neatly ruled score-out lines gave me a little masterclass on how he’d tightened the prose on the page. (Shorter self-editorial Jon: cut.)

Paul McAuley spoke about SF — how it isn’t a literature of prediction, but of possibility — and told us how his latest books, The Quiet War [Purchase] and Gardens of the Sun [Purchase], had been “inspired by robots”: specifically, the robot probes that have sent us astonishing photos of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. To the accompaniment of a slideshow of some of these photos, Paul explained how he’d started with a human being standing on an ice cliff on one of these moons, under a sky full of Saturn, and thinking about who she was and how she’d got there.

I began by saying that my novels showed an almost embarrassingly direct connection to whatever the big issue was in international relations at the time: the collapse of the European socialist states is looked at from various angles in the Fall Revolution books; the brief confrontation between Russian and NATO troops at Pristina airport (where James Blunt, we recently learned, saved the world — but at what terrible cost?) kicked off the Engines of Light trilogy; my recent novels The Execution Channel [Purchase] and The Night Sessions [Purchase] deal with the War on Terror; and my latest, The Restoration Game [Purchase], looks at the back-story of capitalist restoration in the context of the Georgia-Russia war of 2008. I then read a few passages from that book.

The detail of Q&A session that followed is more than adequately covered in Stephanie Carvin’s live-blog, as is the roundtable, where she caught nuances and references that I didn’t. So, instead of re-hashing, I’m going to summarise what I learned from the discussion about how some IR theorists see, and use, SF. I must emphasise that this is my own impression, and shouldn’t be taken as what anyone there said. It’s — to use a distinction I made earlier — a reflection on, not a reflection of, the discussion and subsequent conversations.

So … the good news is that some IR academics take SF/F, including it’s pop-cultural manifestations, seriously. The profession as a whole doesn’t take it seriously enough to allow anyone to make it their “main gig”, but doing some secondary work in the area is respectable enough to look good on your CV. Why do they do it? In some cases it’s because they’re already fans, and they enjoy writing about it. In others, it’s because they’ve chanced upon some work — Star Trek, in Neumann’s instance — and got hooked by it. In all cases, they find SF/F a useful resource on a number of levels.

One is popularization, whether it’s throwing in Buffy references to get students to sit up and listen, or writing articles and even books explaining different IR theories — realism, constructivism, neoconservatism, etc — by looking at what each would recommend in response to a zombie threat.

Another is as a rich source of thought experiments, scenarios, and counter-factuals. The first series of Star Trek, Babylon 5, and Banks’s Culture novels can be used to raise questions about liberal and/or humanitarian intervention. Battlestar Galactica invites thinking about the War on Terror. Blish’s Cities in Flight [Purchase] imaginatively extends Spengler’s grand narrative of history; and, to take an example Dan Nexon used, the Fall Revolution books provide an example of the application of ‘horrifically bad theories’ of Kondratiev long waves and historical cycles. In general, reading and discussing SF/F helps them to think about a wider range of possibilities than they’d otherwise consider.

Finally — and this is my own opinion entirely — given that the very close and often personal connections between the academic discipline of IR and the real-world application of political power and military force make it one of the most intensively politicised and ideologically patrolled groves of the academy, talking about SF/F enables academics to discuss sensitive issues without undue damage to their prospects.

Rather to my surprise, all of this seems to be going on without reference to or interaction with (or even much knowledge of) the academic study of science fiction itself. There are real opportunities there for both sides to develop that missing interaction, to their mutual benefit.

I’ll conclude with what I found the most memorable remark, from Iver Neumann:

Weber was wrong – we are not living in a disenchanted world. Religion is not about belief but about moving to another ‘dimension’ and coming back changed. People don’t see the angels in Battlestar Galactica, even though it has angels all over it, and that’s why they don’t get the ending!

Audio of the panel session is available as podcast from the LSE. Download the MP3 file here.

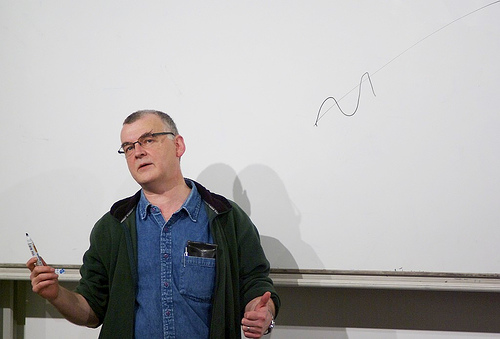

In his presentation Ken mentions a photo of him drawing on a whiteboard to illustrate a point. Here is that photo, which was taken by Billy Abbot and is used with his kind permission.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting Salon Futura financially, either by buying from the Wizard's Tower Bookstore, or by donating money directly via PayPal.

This was very interesting. Having just completed my PhD in International Relations and a big fan of SF/F, it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot, and certainly something I’ve been noticing more and more as my studies progressed and my SF/F reading continued.

If it only we could make it a “main gig”…